By SAHIBA GILL

There was no after-the-rain smell when I was in Varanasi, not even along the river Ganges where waters are wide in January; the white fog curtain erases the farthest bank so that just sky, boats, and water make up the shore. In the city’s brown streets, trash runs steadily through silt-carved gullies. Waste sandcastles build in its empty lots. A diverse and growing mud stews beneath its stilt-top shops. I am a guest in a brownstone in Benares, as locals call their city, a few narrow alley turns behind a main road down a path too narrow to collect anything but chai cups and manure. In the morning, a man retches loudly as he brushes his teeth from his window. Behind my bedroom, a rusted water pump heaves. Children cry mercilessly. A pack of dogs tumbles with their fangs bared. At night, I listen from my bed to the quarreling families whose screams cross the street between our homes.

A family of four lives here. The house in Assi Ghat is eight hundred meters from the river, five narrow stories on a stately row. Its front steps lead to two old doors, a heavy lock between them, and on each a blue postcard of the Hindu god Shiva, anointed with orange paint. On the door, the remnants of previous newspaper-print gods are washed away except for a scrap of eye. Each day the young cleaner walks up and down the stairs and around the third floor with a grass broom, sweeping dirt from the bathroom, kitchen, and living room out any of three thin balconies. Its marble floors are empty except for a sofa, cabinet, rug and TV.

To the city the house is porous. On the third floor, a French door to each balcony usually stands open. The cook, her brother, the cleaner, her mother, and the dishwasher and his wife (the cook’s aunt and uncle) all transact across that hub throughout the day. From the front balcony and through the open doors, they call to each other and friends passing by. The young and talented cook has a white new cell phone, but among the staff no one else does – hers jauntily sounds “Gangnam Style” when her mom or friends ring. Some hours before dinner, she sits on the hard floor watching soaps with the cleaner in the evening cold, making the most of pea season and shucking them into a bowl. There is a system for ferrying items from home to street and back using a rope reeled down from the front balcony. We sent mostly the house keys down, but also religious donations, which an old woman came asking for. The cook gave her a tenth of what was asked. The neighborhood is dense with potential devotees.

In Benares, temple spires rise high along each curve of the river Ganges, which marks the eastern boundary of this ancient religious city, Hinduism’s most sacred. On its west bank, thousands of gods look out onto the city’s passageways from their decorated shadowbox shrines. The destroyer Shiva made his home in Benares, and in a religious real estate boom, all the gods followed him to take up permanent residence in this holy place. Later Shiva caught the Ganges in his hair as it fell from the heavens, and channeled its flow through Benares from the Himalayas to modern Bangladesh. On Earth, the river bestows supreme spiritual boon – post-mortem liberation (akin to Buddhism’s nirvana) from the cycle of life and death – to anyone who dies in its city, who is dispersed as ashes along its shores, or dips even a toe into its waters. On morning walks along the brownstone’s closest stretch of river, I see men towel off from their river baths on sets of stone steps, or Ghats, that lead into winter’s mist. A herd of pilgrims was usually en route, disembarking from a riverboat and shuffling onto tour buses waiting nearby.

The riverside view is like an urban meditation break: the only still panorama in a city whose booming modern population has produced a noxious overload of smog, car horns – and always, trash. That relationship between the Ganges and the city it sooths is a geographic analogy to spiritual transcendence and the mortal life it sublimates. In Hinduism, each person has a true self identical to the universal spirit. So, finding your true universal self entails losing your human self, with its necessary worldly attachments to, at minimum, the body. The dead do this naturally when their cremated bodies are distributed into its holy waters. Bathers hope to do this when they wash their sins away in the Ganges. Sadhu priests train to do this by testing their attachment to their own flesh, renouncing food and physical comfort through rigorous fasts and yoga practice. But the promise of finding yourself also brings many secular pilgrims to Benares. While they too are in search of ways to lose themselves, they disbelieve in the cleansing power of a Ganges bath – religious or otherwise – since the river has been steeped in toxic chemical and human waste dumped from upstream.

Instead, these secular pilgrims make their own bodies the site of transcendence. Mortal life remains embodied in the fantastically ruined city, but instead of physically going to the Ganges to escape it, visitors try to keep their minds as tranquil as the river’s holy waters against the thrall of Benares’ rousing streets. The many writers among them describe denying full use of the senses as a common way to distance self and body. For example, Allen Ginsberg journaling in Benares in 1963 described himself as being in a “morphine haze,” inert while outside men heaved bags of dung over their shoulders for pay. In this millennium, Geoff Dyer’s title character in Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi argues that like in a video game, all semblance of individual agency in Benares is an illusion. The game sets the boundaries of the characters’ power, just as in illimitable Benares the intensity of the city pressures its inhabitants to adapt to its fetid ecosystem. In company with many others, both authors seem tempted to sink down into the wet streets of the city, liberating their souls to be skimmed off their bodies like the skin that forms on top of hot milk chai.

Though the neighbors’ intrusive teeth-brushing continued to be my daybreak alarm during the month I lived in the Benares brownstone, after latching the heavy warded lock of the door to begin my morning walk I found that the fetid street pollution that used to disturb me began to fade away, whirring as innocently as white noise. Each day in Benares I was numbing to the ambient chaos. With the loss of senses, I had gained a rare A.M. quiet. Was this the beginning of my blessed descent into the mud?

The brownstone’s stalwart walls seemed to frown on that liturgy, devoted instead as they were to the vast world of birthdays and sibling quarrels, existential in their own way, too. The stairwell of the brownstone had plaster floral grates on each landing that looked onto one of the rooftop homes of adjacent shorter buildings. The cook came in early morning to make chai from one, and the cleaner came in late morning to do the family wash from another. The house was porous, but only in service of keeping its family clean and fed. Upstairs the two children played away their last days of winter vacation, while in the open narrow bathroom doorway of the crayon-scratched third floor wall, the cleaner set to work. She was small, and even smaller when crouched in the white tiled chamber among a still life of plastic buckets, raking the clothes across the wet floor. Meanwhile the cook sprayed tap water over breakfast’s steel dishes and began to clean. In the wizened brownstone (and incidentally, in many Hindu sects) transcendence was a task for the next life. This one had plenty of its own to-dos.

I came to Benares because I wanted to learn Hindi, and the first reputable hit I found for teachers in India was based there. The brownstone was my teacher’s recommendation for lodging a language student. With its opportunities for Hindi practice, home life suited me; I had not given any thought to transcendence except as the experience of authors like Ginsberg who were without Hindi grammar to preoccupy them.

Yet as I read in Benares their accounts of the city, I found myself tempted to follow their journeys toward self-transcendence. Each time I returned to the brownstone, I felt like a walking biohazard. Walking with shoes up the stairs meant bringing mud and feces onto the surfaces I would later scale in socks. Smoke from crematory pyres seemed to linger on my hair hours after the corpse would have gone to ash. When I brought them home, the bright foil-wrapped snacks that hung like Christmas tinsel in the tiny corner shop betrayed a film of dirt they had gathered from the air like dust. I wanted to escape the body that seemed to bring debris into the domestic sanctuary, and like the writers who sank into the streets, be able to sink into the house.

My piece of that transcendence began in the corner of the small kitchen counter next to the refrigerator, with a steel pot of purified water the family kept for cooking and drinking. Fetching a drink with a steel cup was a small but regular task. When I was new to the household I kept finding my fingers making contact with the water. My solution was to suspend the cup as I drew water by pinching its rim between my forefingers and thumb. The task, paradoxically, was to catch the water while avoiding it. My shoulder and elbow went akimbo in order to perform it. The medium was not Ganges water, which would bestow its liberation instantly. Instead, the habit itself became a lesson that cleanliness in Benares would require the reassurance of my own daily handwork. In service of transcendence, it was impossible to erase myself from the house. I could only reproduce the house’s cleaning rituals on my own scale – within the scope of my hands. Just as the writers aimed to sink into the muddy streets, I aimed to blend into the diligently kept house.

It was a paradox that in Benares, both dirt and soap could be means to transcendence. In fact, if the role-switching between house and city was to be accepted as transcendence, it seemed a poor reward in comparison to the existential liberation the Ganges promised. Transcendence was supposed to be like the universal soul – constant and eternal. The premise behind writers’ quest for stillness in Benares’ frenzied streets seemed to be that if you could find yourself there, then you could find yourself anywhere. Nowhere could strengthen inner sanctity against the world so well as that extreme city. But with home and city remaining so distinct, the brownstone walls cast doubt on that hope. Perhaps the issue had been easier for the writers, who seemed to limit their scope to the city streets and temples only, where a single transcendence seemed possible. Yet my stay between house and city was not so far a stretch from their view that I did not think that transcendence, self-avowedly universal, should expand too.

The brownstone itself grew for me when the family told me about “the best spot in the house,” up a spiral stair case on the roof to a tower that mounted on the five story house walls, far surpassing the height of any perch in the neighborhood. Fifty-odd concrete roof plots tessellated on the city’s skyline all the way to the leafy horizon. Each patch on the neighboring roofs had in it a family doing small errands, as though the roof was a combination backyard-kitchen-bathroom. Couples and female friends held spoons to fry vegetables and palmed soap to scrub children; women pinched clothespins and saris as they hung lines of bright dried laundry. On the roof, arm-length cleaning rituals constructed homes – not just one but the entire rooftop panorama before me – a welcome respire from the third floor of the brownstone. Here, laundry was a movable divider between neighboring patches. Since they did not have permanent walls, residents turned away from nearby strangers, and like park- or beach-goers, created an inside space in the open air. Without any fixed form, the homes were not necessarily separate from the city until daily life began each day and made them so.

I had escaped the home/city divide; on the roof the only thing between me and the sky was a smattering of kite strings. Yet the expansive geography did not offer any universal transcendence. I wondered whether the writers, left in the dark riotous alleys below, had ever found such a perch from which to consider their search for transcendence. But I doubted it. They seemed to prefer to put their souls through the fire of Benares streets. Perhaps the wide gradient between soul and street did strengthen the resolve to transcend, but in Benares the boundaries between self and world were already thinner than most, as was its boundary between heaven and earth, the thinnest such tirtha in Hinduism. Here, where people could control both city and home with the motion of their hand, it also felt as though you could both lose yourself in the elusive distinction between places and find yourself in the construction of the boundaries between them. And all that without disappearing, like the writers, into the mud – a fate even the dying did not want.

One of my last mornings in Benares, I watched the cremations along the Ganges from the second floor of a grand abandoned veranda at Marnikarnika Ghat. In the soot-blackened concrete shell, I found three women spinning thread and conferring benedictions while they waited for their old age to end. I had tithed them in exchange for their prayer and the view. But they had since dispersed, squatting in shadowy far corners as though they too, like this living corpse of a building, lingered between life and death. But, as a shifting wind brought funerary ash sailing into the room, I saw one dying woman rise, then bending at the waist, take a broom in hand and begin to sweep.

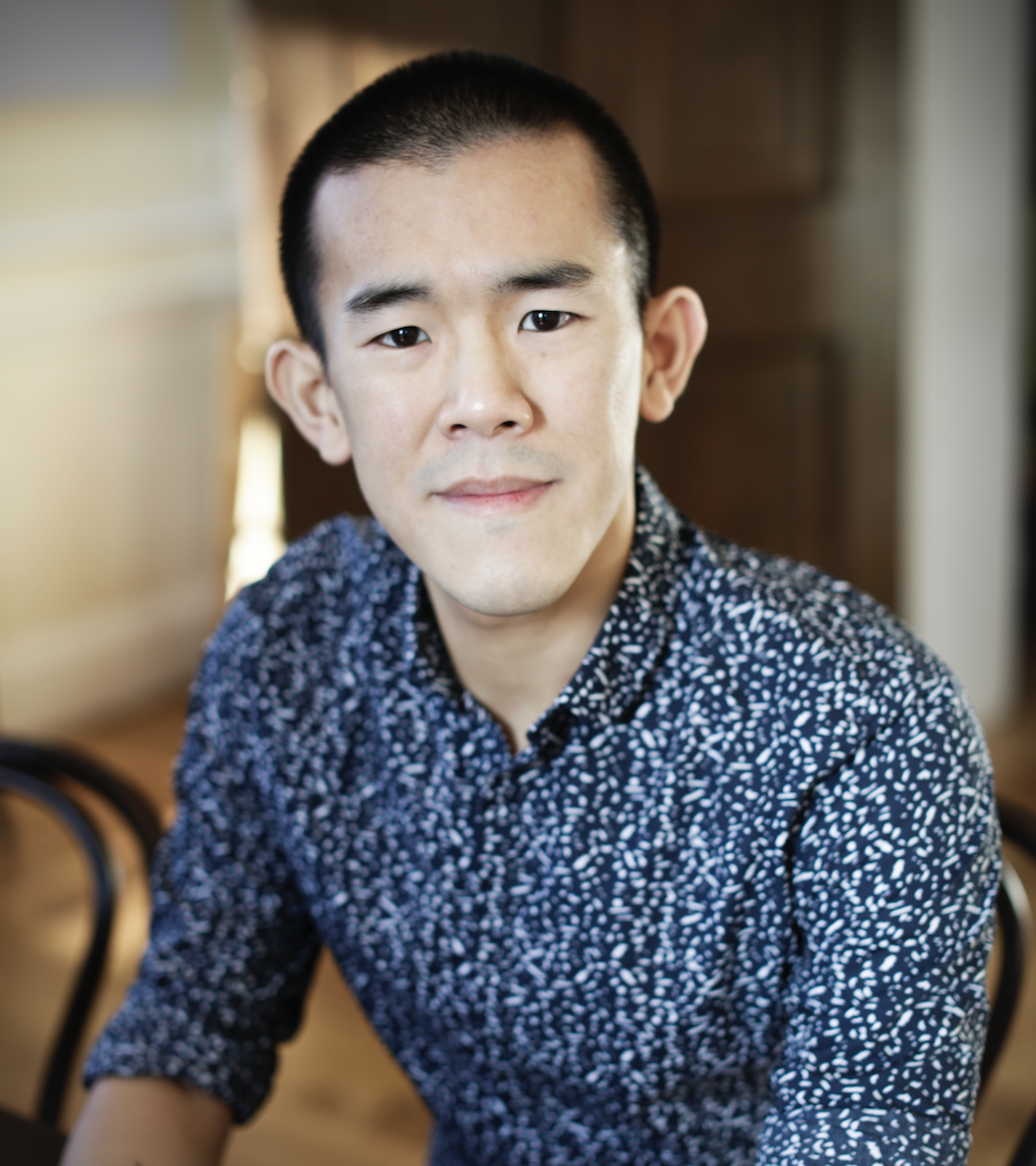

Sahiba Gill is Assistant Editor at The Common and a Global Academic Fellow at NYU Abu Dhabi.