By ANNA BADKHEN

We are in the market square in Djenné, in central Mali. Ali the Griot holds court on a low wooden stool by the pharmacy. He chants:

“The Fulani came from Ethiopia: first the Diallos, then the Sows, then the Bâs. The Bâs had the most cattle; their cows are white; they give the most milk; from that milk comes the sweetest butter.”

He chants:

“Do you know Amadou Cissé? His ancestors lived in the bush and herded cows—and this Cissé has no cows, he lives in town, and he works as a guide herding white tourists!”

An old man on a motorcycle pulls up to the pharmacy. His boubou is starched and very white against the laterite dust of Djenné’s unpaved streets, and the watch on his wrist looks golden. He recently has sold his cows to pay the bride price for a second wife, and to buy a television for his city home. The griot chants:

“He has nothing now—just his penis.”

Passersby snigger. The old man just stands there. No one dares contradict a griot, a hereditary documentarian, a descendant of historian-poets who, for hundreds of years, have preserved and passed down through bloodlines the ancestral sagas of their neighbors. A griot decides whether to keep or broadcast people’s iniquities and virtues. His praise and reprimands stoke or resolve conflicts, bestow or retract fame, devastate or strengthen. Only a blacksmith—who uses fire to forge matter out of nothingness—evokes more awe.

The scholar-traveler Ibn Battuta, who wrote about his visit to Mali in 1352, found griots repugnant, their performance comical, and, in the chapter he titled “Account of what I found good and what I found bad in the conduct of the Blacks,” lumped them with sinners: “Other bad practices are the clowning we have described when poets recite their works, and the fact that many of [the Malians] eat carrion, dogs, and donkeys.” But the Djennénke know better. They submit to the griots’ fearful poetry because it comes from the very forces that helped shape the universe. They recognize the awesome power of storytelling.

Bruce Chatwin proposed that, as the indigenous Australians’ totemic ancestors had sung into being a geographical score at the era of creation they called the Dreamtime, so had the first humans sung their way across the world. The poetry of those first songs, says Chatwin, was the original poïesis, creation. In a manner of speaking, it was: the command of complex language may have enabled our ancestors to share plans and gave them the cohesion to strike out of Africa some sixty thousand years ago. Stanza by millennial stanza, we talked ourselves all the way to Patagonia.

That initiatory song is unceasing. It enacts its magic again and again in myriad individual instances of becoming: When a mother names everything to her infant. When new lovers point out to each other a moonrise, a sunset, a freckle, as if these had never been seen before. Look! Look! Each story is foundational, each makes the universe afresh. Like a griot’s testimony, each creates a new world and a new way of being in it. When a writer tells faraway stories, she sings the Other into existence on the page. We can only create dangerously, because every story is loaded with the potential to transform lives, profoundly and at random.

On the surface, my storyteller’s work is straightforward. I enter a community, a culture, and cut an unambiguous covenant with my hosts: I will absorb their caring instruction and recount their story to the world. On a planet constantly redefined by the Anthropocene, where avarice and technology rend and throw together landscapes, and megacultures subsume whole ways of seeing, their accounts testify both to our connectedness and to the astonishingly different ways in which we are alive.

Two years ago, to research a book, I plodded around the Malian Sahel with a family of Fulani nomads. The Fulani herd their lyre-horned zebu cattle on foot, keeping the pace set twelve thousand years ago, when a man first took a cow to graze and committed to life on the hoof. It is a pace as old as Abel. Two thousand footsteps per mile. Twenty to forty thousand footsteps a day. Seven to fifteen million footsteps a year, chasing rain in the African savanna, faithfully hugging the routes hewn by centuries of common sense and bad habits, with minor deviations for temporary things—crops, droughts, borders, wars. Every footfall is an umbilical cord that connects the Fulani to the very first cowboys, reminds them of who they are on Earth. Every footfall propels the narrative of being human.

In West Africa, the right to spew blessings and augury is a matter of caste. A griot is born into it, anointed a poet in the womb. And who appointed me, a stranger, a storyteller from the edge? The responsibility was immense: I could be the single conduit between my subjects and my audience, their only megaphone. No other would document, mile after mile, the stories of loss and redemption and fear and love that Fulani nomads tell round the campfire on ancient transhumance routes. Everything was at stake.

“You catch the snowflake but when you look in your hand you don’t have it no more,” an old brujo tells the boy Billy Parham in Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Crossing. “If you want to see it you have to see it on its own ground. If you catch it you lose it.” Who gave me the right to package something so magical, and why? What if all life could be beheld truly only on its home ground?

“Things separate from their stories have no meaning,” a Mexican hermit priest tells Billy later on. But what about stories separate from their things?

The maddening paradox of representation lies in the innate contradiction between the moral imperative to expose the world’s iniquities by honoring the lives these iniquities most affect—and the constant doubt in the right to render something so exceedingly private, to distill it the way one distills an essence. To exhibit it apart from its context. To transpose it onto a different context: my own.

The year I spent with the nomads, I was missing someone very much, and my sadness clung to the savanna like wet silk. It contoured everything, created a frame of reference of its own. As my hosts migrated, in each of their footfalls I saw a separation. I saw them leave behind loved ones, lovers, graves. I saw them shape their living within sequences of holding on and letting go, trying to accept the transience of everything—and to embrace man’s innate impotence to accept it. My narrative of their journey is an imperfect decoction of a world seen through my particular tragicomic bird’s mask.

Neuroscience explains that such inadequacy is predetermined and unavoidable. It is a function of anatomy. Something particular—this melancholy song of a milkmaid, that solitary cattle egret like an enormous lotus blossom descending—stirs the storyteller’s neurons to respond, reverberates off the memories they store. Except these memories themselves are malleable, unreliable, even possibly untrue. Our brain may even create them on the fly, in the very moment of the encounter, when something indefinable in the unique and ephemeral soundboard of our cortex is strummed just so and resounds. Neuropsychologists call such memories, ominously, “false,” “ghosts,” “superposition catastrophes.”

“Creativity … is largely unpredictable,” writes the cognitive psychologist Margaret A. Boden. “The most important reason is the enormous complexity, and idiosyncrasy, of human minds, the detailed contents of which are largely unknown even to the individual concerned.”

In other words, what we elect to see and how we see it is irrevocably conditioned by our history, our longings, our joys, the way life appears to us in the specific moment of seeing, and our impulse to draw connections, identify patterns, establish syllogisms. The modest call it a coincidence and, virtuously, stop at that. Writers take or create context, then fit life into it. The result is a story.

It is a paradigm Eliot Weinberger—writer, poet, editor, translator—describes in his essay “The Desert Music: South” about the mysterious geoglyphs on the Nazca plain in Peru. For almost a hundred years, people have been trying to decipher these lines. “The plain mirrors one’s own preoccupations,” writes Weinberger: some see celestial data, others engineering feats, or runway markers for UFOs. Toward the end of the essay, Weinberger reveals to us what he himself perceives. “Nazca, empty of the forms of life, was pure description itself: the world turned into writing, with the plain as its page.” Of course. He is a wordsmith: he sees a text.

Like most sacred rites, storytelling usually happens at night. This makes sense. It is easier to imagine different realities in a dark void, where nothing distracts the mind and possibilities seem limitless. It is like closing our eyes. Gretel Ehrlich tells us that in Qaanaaq, Greenland, where the sun goes down in October and does not rise till February, the dark months are “a deep, rich period of storytelling.” Fulani nomads tell stories after dinner, after the campfire has grown cold and the children have jigsawed themselves on thin moonlit mats under their mothers’ skirts and grandfathers’ blankets.

The nomads are egalitarian storytellers. Men, women, and older children take turns, piecing together new worlds in equal measure from the ornate allegories of Islam and griots’ incantatory oral histories and ancient animalistic parables that traveled on transatlantic slave ships to become tales about Br’er Rabbit. They populate these worlds with cowboys whose herds spill beyond the horizon, water spirits that feed on human eyes and bellybuttons, spendthrift youngsters who squander their inheritances of cows on women and cigarettes, herders who lose their pasturelands to the intensifying drought or to the global war on terror that is ravaging traditional nomadic routes on the edges of the Sahel. Hunters, griots, elephants.

At the end of each anecdote, the listeners click their tongues in appreciation. Then they say:

“Good story. Go on.”

Our need for stories may be coded in our genes. It is an instinct, says the art philosopher Denis Dutton, that we use for sexual display, for pattern recognition, for bonding, and to interpret the world. The art theorist Brian Boyd says storytelling is a specifically human adaptation, an ancestral cognitive tool we use to identify ourselves. This takes us back to Chatwin, to griots, to John 1:1, to narrative’s foundational power to chart our humanness.

Still, scientists acknowledge gaps in our understanding of the purpose and mechanisms of the art of story. In his book The Storytelling Animal, which draws on modern neuroscience, art studies, psychology and evolutionary biology, the evolutionary literary scholar Jonathan Gottschall concludes: “Nothing so central to the human condition is so incompletely understood.”

A good story leaves room for the indefinable. Gottschall allows, too, that “story may be for nothing at all.”

My hosts trusted me to convert their intimacies into stories because they wanted people beyond the Sahel to hear about their life. They encouraged me to write things down. They made sure I sketched the right number of teats on a cow’s udder. (Four teats.) Maybe they understood that bias was inherent to any narrative. They live a premodern lifestyle, with no access to radio, television, or Internet, and they must have learned, over centuries of listening to stories told by griots, marabouts, and other nomads, that every storyteller introduces distortion into her tales. Perhaps they even like them for the flaws.

On storytelling nights they would ask that I tell them stories, too—about the emergence of stars, about lands so cold that snow covers pastures for months on end, about human origins. My accounts were improbable, my context strange, my perspective biased. The Fulani accepted all of that as part of the bargain. Their scabrous savanna had given birth to magical realism, and it has room for everything else. They judged each story on its own merit as a map of a new territory, a journey someplace ineffable, a way of being that offered some new wholeness.

There is a different way to describe Chatwin’s idea that people had narrated the Earth into existence. He was a writer and a wanderer, and he envisioned the perfect union of his two passions, a Dreaming-track song. If we fall in love with the world of his distinct creation, it is because it surprises us, takes us someplace new, resonates in some insatiable cavern within that forever wants beauty. It strums something that makes us say: Yes. Good story. Go on.

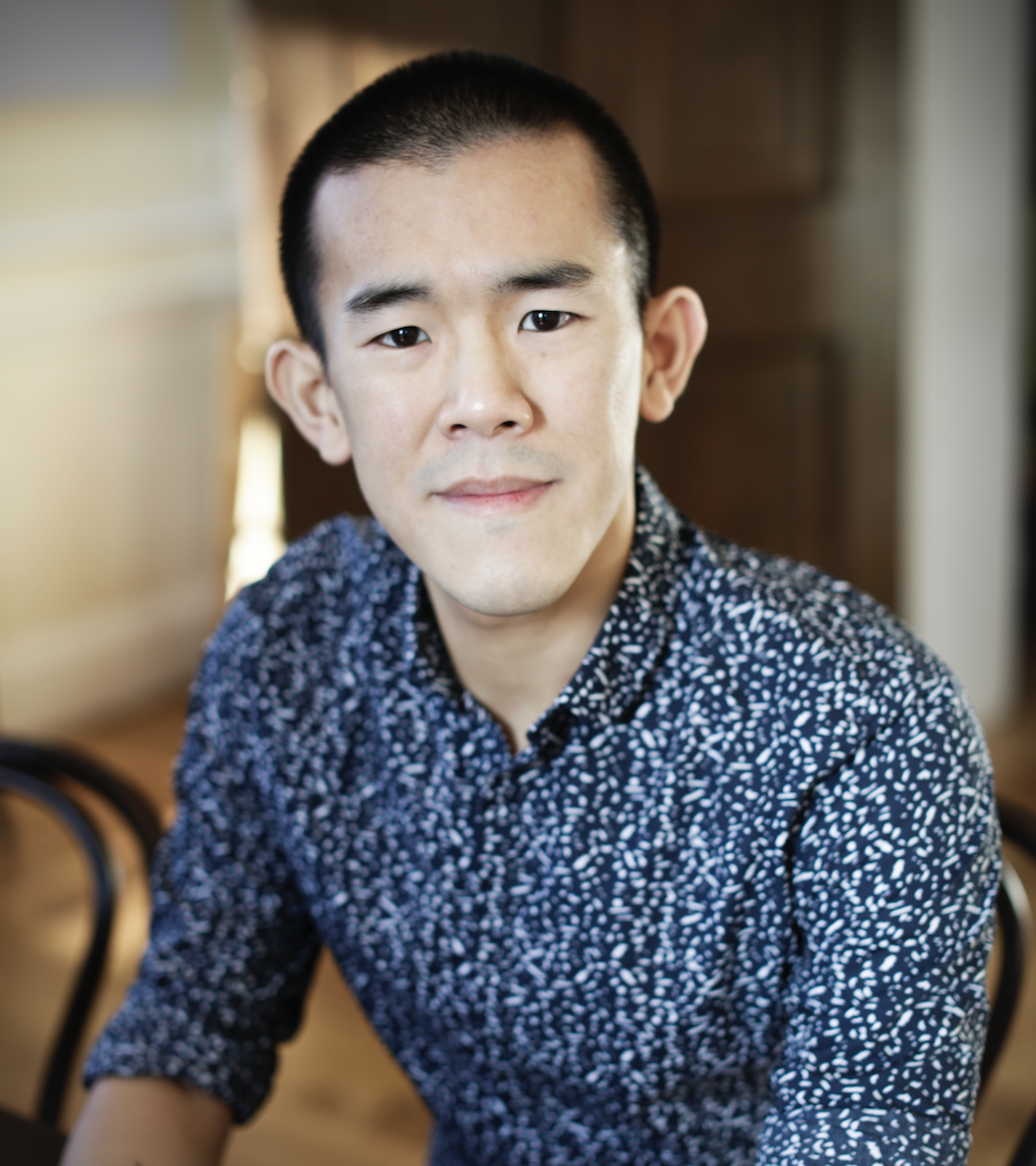

Anna Badkhen is the author of five books of literary nonfiction, most recently Walking with Abel, a book about transience, out in paperback this summer. She writes about people in extremis and is currently at work on Fisherman’s Blues, a book of magical nonfiction about fishing and boundaries.