ALEXANDER BISLEY interviews RICHARD FORD

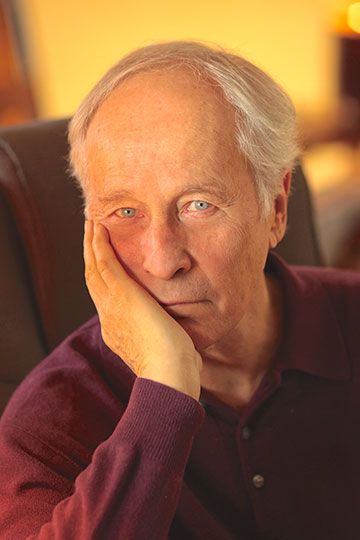

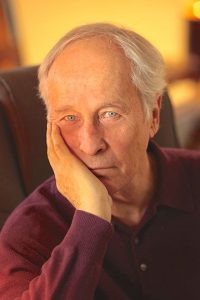

Talking to Richard Ford, the 76-year-old author of The Sportswriter, Independence Day, and Between Them, provides some hope, a feeling of being somewhat consoled. The great Southern writer is considered and insightful, with that courtly Mississippi inflection. Evoking his classic A Multitude of Sins, Ford’s latest short story collection Sorry for Your Trouble proves he still has gas in the tank.

Richard Ford is the author of the New York Times bestseller Canada. His story collections include the bestseller Let Me Be Frank with You, and Rock Springs. His novel Wildlife was adapted into a 2018 film of the same name. He is winner of the Pulitzer Prize, the Prix Femina in France, the 2019 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction, and the Princess of Asturias Award in Spain. Born in Jackson, Mississippi, he now lives in Boothbay, Maine, with his wife, Kristina Ford. Sorry for Your Trouble is out now from Ecco.

During the days leading up to President Biden’s inauguration, Ford and Alexander Bisley discussed sport, place, process and America’s future.

1. I recently reread your classic The Sportswriter, in preparation. Numerous passages resonate with me, including: “But in these literal and anonymous cities of the nation…your St. Louises…even your New Jerseys, something hopeful and unexpected can take place.” In this challenging period for America, do you still believe this?

Yep, I still believe it. I still believe in the possibility of romance. I still believe in the possibility of illumination. I still believe in the possibility of renewal. Most of which can be achieved through the agencies of literature.

2. Is America going to improve in 2021?

I don’t know. It can hardly fail to improve. I mean the harm that has been done to America, and I don’t mean to say structurally but in its spirit, is going to be hard to put back up on its wheel. So I’m glad for Mr. Biden. I certainly voted for him. I certainly wanted him to be president. I certainly think he’ll be a good president. But his problems are monumental and they are chiefly bound up in the fact that 71 million people voted for this monster Trump and they’re not going away. They don’t think they’re wrong. Probably some of them aren’t wrong, but most of them are. They’re citizens, they’re going to be listened to, and they’re going to have a force to play in the country as it becomes itself again, so I really worry about that a lot.

3. Do you laugh enough these days?

Absolutely not. No, I don’t laugh enough at all. One of the things that makes me laugh the most is the books that I’m writing, especially from these Frank Bascombe banks. Most of my laughter comes from that. There is not very much to laugh about in the United States these days.

4. Staying on the sadder side, does death remind one of our responsibilities to a larger world?

I don’t feel any formal responsibility to a larger world. I feel a responsibility to my readers. And I try to find more readers to tell them the things that literature can best tell people. To say you have responsibilities to a larger world would in some ways impinge on my freedoms. The freedom to do what I want to do and write what I want to write is responsible only to me. Literature can do those things, if it wants to. But I’ve never felt it was my responsibility to do anything other than what I please.

5. In reference to your Frank Bascombe books, you’ve talked about the “vital necessity of the play of light and dark” in literature?

It originates in that notion in Henry James, in which James says at the beginning of his little novella called What Maisie Knew, “there are no themes that seem so human as those that reflect out of the city of life, the relation between bliss and bale, between the things that help and the things that hurt.”

You know the two sides to the drama, one grimacing the other laughing, that seems to me to be the essence of what it’s the most worthwhile to write about. Being a writer means that you are invested in the future. Somebody you don’t know in a place you don’t know, maybe at a later time, will find some use in what you do.

6. You are writing your last Frank Bascombe book at the moment?

It must be the last one. I’m 76, I don’t know where I’ll find the energy to do another one. It’s called Be Mine. Frank is now in his 70s and taking care of his terminally ill son Paul.

7. How did your two years living in Paris influence your thinking and writing?

It gave me some things to write about. It gave me some places, some locations where I could set things. That was very useful. It made me feel very writerly to be able to be an American from Mississippi writing stories set in Paris. It made me feel very cosmopolitan, even though I’m not. That was great. Influence is such a tricky thing, such an indeterminant thing. I wrote a few stories that were set in Paris during that time and after that time.

8. Between Them, your superb memoir about your parents, puts us right there in Mississippi.

Mississippi is a place that I should be able to write about with some fluency. But I find it kind of a challenge because I knew it when I was young, and it was also so much a part of my reading experience with [William] Faulkner. To really have my own fast grip on things that are in Mississippi has been hard in a way. Nothing I do is hard, OK. It’s just been a little more demanding than usual. Being a writer is not hard. Anybody who tells you otherwise, hold on to your wallet.

9. I liked Paul Dano’s film Wildlife, adapted from your Montana-set book.Do other adaptations interest you?

I thought it was an interesting little picture. He made some great changes to my book. He corrected a couple of problems that the book had, which I thought was very generous of him. So all in all, I was really very pleased with how Paul did that. If he wants to have, he has a future on that side of the camera.

Someone called me about doing a film of Canada recently, which I think will make a good film. For several years HBO had the Bascombe books all under a rather nice paying contract, but then they let it go. That’s funny money to me. I don’t expect it and if it comes I’m happy for it. But I never really think about the movies. I certainly don’t work in the movies so it’s just not a thing I must think about. Sometimes it pops up and you’re “good that’s it right there,” but then after that I don’t think about it anymore.

10. Has your writing process changed?

My writing process hasn’t changed since 1982. I still do things the very same way I’ve always done them, which is a rather draconian immersion in raw material. Which is what I figured out how to do when I started writing The Sportswriter, and it seems to set me up to write the book I want to write each time. I do the same thing with stories as I do with novellas and novels. I accumulate a great deal of raw material. Then I study and immerse myself in it, more or less memorize it, and then I try to figure out a way to write myself forward.

I write with a ballpoint pen, as I always have written. I rather like making letters on the page, I like the homemade quality of the whole thing. It’s onerous that eventually I have to type it up on my computer. That’s a very useful editorial process to go laboriously through all my handwriting, and try to figure out what I wrote.

11. Do you still enjoy teaching?

I do. I really enjoyed teaching my graduate students, my literature seminars at Columbia. I only teach one course a year and I really do quite enjoy it, largely because I like being in the room with my students. I like the books that we get to read, really good books. I’m lucky to be able to do it…Out of this Sturm und Drang [America’s current situation], great literature will emerge, I’m confident of it.

*

Alexander Bisley’s previous interview for The Common was with Viet Thanh Nguyen. Further literary profiles include Paul Theroux, Tony Bourdain and Karl Ove Knausgaard.