When I nurse my baby son Oliver to satisfaction, a beautiful look grows on his face. His small damp lips purse; his cheeks pinken; his black lashes rest delicately shut. If I try to offer more, those lips squash upwards in contented refusal. “You’ve o’er-brimmed his clammy cells,” my partner Paul always observes.

He’s quoting of course from that most beautiful of poems, John Keats’ To Autumn.

To Autumn was the last of Keats’ great Odes. Just over a year later, at age 25, he would be dead of tuberculosis. When he wrote his Odes in 1819, he hadn’t yet been diagnosed with the disease, but death had already profoundly marked his life. Both his parents died in his youth; his beloved brother Tom had succumbed to tuberculosis the year before, nursed to the end by Keats. The poet must have known his own infection was likely.

There’s something modern to my ear about To Autumn amid the ranks of Romantic poetry, despite its sometimes quaint diction. In contemplating the penultimate season of the year, Keats captured something indelible. As so many of us straggle to the end of a long winter confined to our homes by the pandemic, To Autumn speaks to both our loss and our longing. Though 200 years old and written in the presence of death, it feeds a contemporary hunger for harmony.

Reading this poem now, in this forced break from the rush of modern life, is a kind of medicine.

*

I’ve always loved that Keats is a poet where you don’t have to dig, search, and puzzle for meaning. Instead, his work’s depth derives from the sheer intensity of his imagery, from the power and breadth of his language. “The excellence of every Art is its intensity,” Keats once wrote, and his work is the apotheosis of that philosophy.

Scholars have, nevertheless, proposed a variety of possible underlying meanings for To Autumn, from a meditation on the artistic process to political undertones. Most obviously, the poem suggests that Keats had reached or was reaching for a kind of peace with the final season of life – whether his loved ones’ or his own. Fall, after all, is a season overflowing with the beauty of impending loss. Keats honors the sorrow of departures with pensive gentleness: “Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?/Think not of them, thou has thy music too,—”

To Autumn is also more than a paean to endings. It’s a lush celebration of landscape; a celebration, not of autumn as a symbol of something else, but of autumn itself.

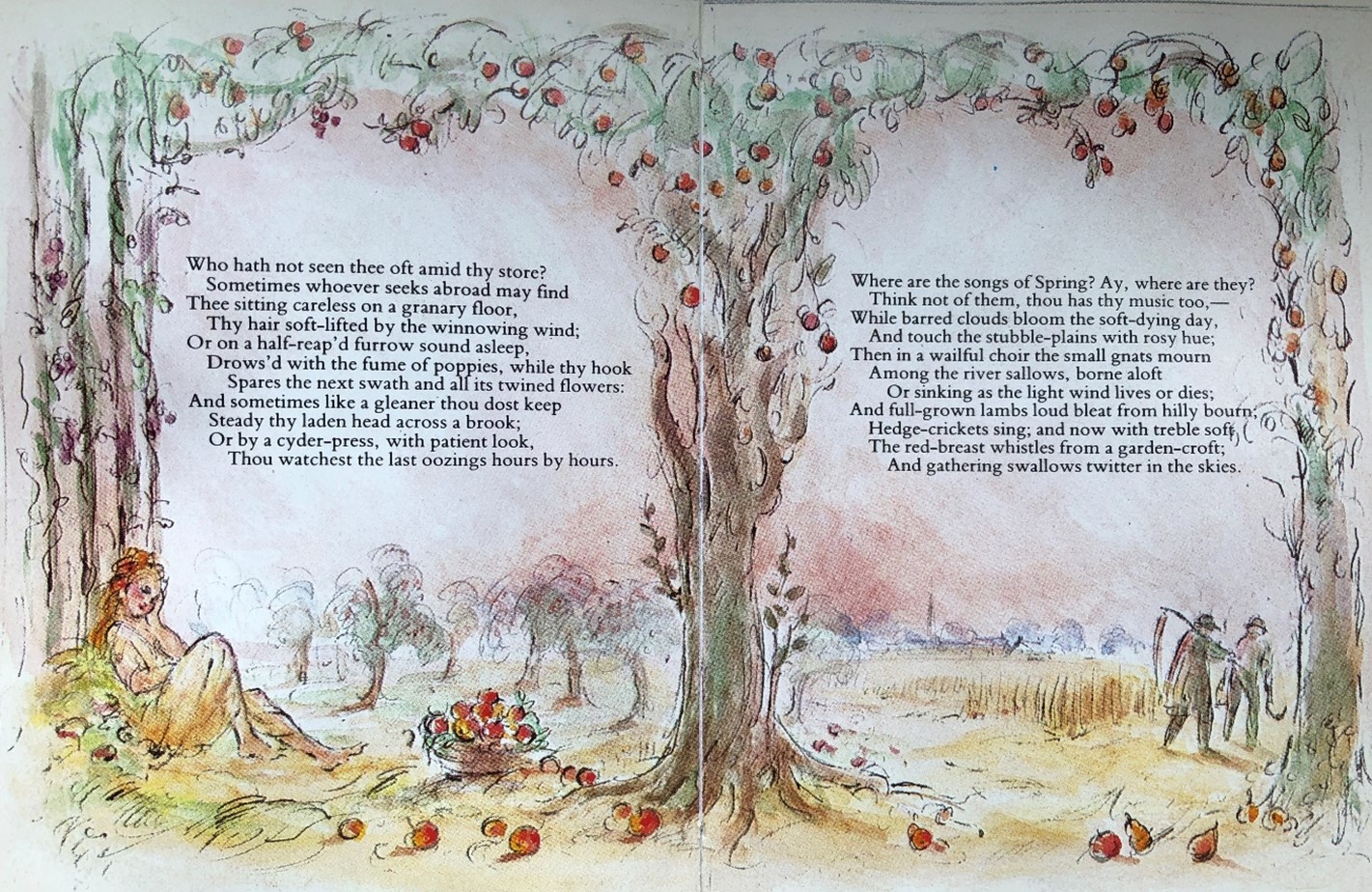

The edition I have at home of Keats’ poems was a gift to me from my parents. A little book barely bigger than my hand, it’s part of the Salem House Pocket Poet series of the great Romantic Poets. Sensitively illustrated by Patricia Machin, the pages of To Autumn have nestled themselves in my heart and mind since my teenage years.

In the illustrations, figures walk a country landscape; the dryad form of Autumn herself luxuriates on a bank beneath a tree. The watercolors of the pages are the same hues that burst from the lines of the poem, even though, miraculously, Keats uses only one color word in the entire poem (“rosy,” if we except the noun “red-breast” as a stand-in for robin). He does the work with nouns, from apples to poppies to a granary to the stubble-plains. Russet, orange, brown; burnt sienna and green; red, gold, sunset purple and peach.

In the illustrations, figures walk a country landscape; the dryad form of Autumn herself luxuriates on a bank beneath a tree. The watercolors of the pages are the same hues that burst from the lines of the poem, even though, miraculously, Keats uses only one color word in the entire poem (“rosy,” if we except the noun “red-breast” as a stand-in for robin). He does the work with nouns, from apples to poppies to a granary to the stubble-plains. Russet, orange, brown; burnt sienna and green; red, gold, sunset purple and peach.

Those shades glow each October outside my New England window, but both the poem and illustrations are English at their core, native to the British countryside that brought Keats into being.

He knew that landscape intimately. Moss’d cottage trees. A half-reap’d furrow. Gathering swallows in the skies, preparing for southward departure. The poem’s three stanzas follow successive phases of the season, from the warm close of summer, to the central harvest season, to the gentle greying and fading of late fall. Fertility and finality go hand in hand as they have since the days of Demeter and Persephone. The poem’s sounds, too, bring me back to the country where I spent my first five years and my partner’s family still lives. Nothing could be more English than a chorus of bleating from a pasture.

As consumption closed in on Keats, he tried to travel to Italy so the warm climate might cure him – a disastrously stormy voyage by sea that sapped the last of his strength. This consummate poet of Britain’s rural glories would never see England again.

As consumption closed in on Keats, he tried to travel to Italy so the warm climate might cure him – a disastrously stormy voyage by sea that sapped the last of his strength. This consummate poet of Britain’s rural glories would never see England again.

*

I was born in England, but I’m now a New Englander to the core. For comparison with Keats, I like a short journal entry about autumn by a great early American writer, New England novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, which opens:

Friday, October 6th, [1843]. Yesterday afternoon … I took a solitary walk to Walden Pond. It was a cool, north-west windy day, with heavy clouds rolling and tumbling about the sky, but still a prevalence of genial autumn sunshine. The fields are still green, and the great masses of the woods have not yet assumed their many-colored garments; but here and there, are solitary oaks of a deep, substantial red, or maples of a more brilliant hue, or chestnuts, either yellow or of a tenderer green than in summer.

Further on, Hawthorne reflects on the season’s “pensive gaiety, which causes a sigh often, but never a smile”:

We never fancy, for instance, that these gaily-clad trees should be changed into young damsels in holiday attire, and betake themselves to dancing on the plain. If they were to undergo such a transformation, they would surely arrange themselves in a funeral procession, and go sadly along with their purple, and scarlet, and golden garments trailing over the withering grass.

I like Hawthorne’s entry as a counterpoint to To Autumn. Unlike Keats, whose peaceful countryside represents centuries of domesticity, Hawthorne’s America retains a stark wildness, albeit one that Hawthorne tries to tame through anthropomorphized imagery. The chestnuts, maples and oaks that have begun taking color are “solitary” in a hulking mass of green woods – a woodland more forbidding in character than Keats’ mellow orchards. The trees “seem to smile,” Hawthorne writes, “but it is as if they are heartbroken.”

Hawthorne laments that he has never done justice to autumn and, I think, a comparison to Keats shows why. Hawthorne romanticizes with superlatives, adjectives and abstractions (e.g., “perfect gorgeousness”; “softness and delicacy”; “the most brilliant display of them soothes the observer, instead of exciting him”). Keats, instead, grounds himself in substance, in soil and fruit and scent.

In Hawthorne’s final lines, though, the waters of Walden Pond cleanse him. The most beautiful and incisive of his contemplation, they encapsulate the craggy fierceness of New England. In those clear waters, he writes, to bathe “was like the thrill of a happy death.”

*

Nurturing new life in a time of death. It’s a strange frame in which to raise a newborn. The pandemic has encircled our nuclear family of three in an iron solitude of parental leave and working from home, broken only by Zoom meetings, masked garden visits here and there, and a handful of coveted, all-too-rare, obsessively quarantined visits to my parents, who are 75 years old.

In Keats’ time, tuberculosis stalked the landscape much as Covid-19 does now. Much like today, poverty and age marked out the vulnerable. Poverty was part of why tuberculosis attacked Keats and his family so virulently. Yet why poverty was Keats’ lot is an existential mystery. Whatever spark of life became Keats was born to his penniless family and no other.

To me, what’s been perhaps most frightening in this pandemic winter is its randomness, the way, despite some risk factors being more flagrant than others, it’s unclear who will succumb. There are unknowable causes that govern our life. We can fight them, and sometimes overcome them, but which of us they strike down and which of us spare, at its universal core, has no answer.

In the untimely maturity of his artistic peak, Keats transformed that randomness into beauty, a landscape enhanced by contrast, the casual grace of a gleaner

“On a half-reaped furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers.”

Keats understood, as philosophers and writers have known throughout time, that life and death are contained in one another: the circle of life, the cycle of the seasons, the ouroboros. Decay is the bosom partner of fruition,

“Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom friend of the maturing sun,

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run.”

I’ve never felt so close to death as in the moment of birthing my baby. A hole into the blackness of the universe seemed to yawn, confronting me with the boundary between nothing and identity, the void from which we yank the stuff of emergent life. For a screaming moment I stared into eternity. From that maelstrom of nonexistence, in an act seemingly too enormous to have chosen except that I did choose it, I brought a soul – one bound in a slippery fragrant body that for weeks felt as foreign to me as an alien until I settled into our bond.

Nursing Oliver while fearing losing my nearest and dearest to the pandemic has sharpened the poignancy of motherhood. As Hawthorne notes, it’s by plunging into waters cold as death that we’re wakened to feeling most alive.

*

No consideration of To Autumn can be complete without a discussion of its prosody. In his Odes, Keats wanted to invent a less clumsy form of sonnet. “I have been endeavouring to discover a better Sonnet stanza than we have,” he wrote to his brother. “The legitimate does not suit the language well, from the pouncing rhymes; the other appears too elegiac, and the couplet at the end of it has seldom a pleasing effect. I do not pretend to have succeeded. It will explain itself.”

He did succeed, with the brio of a true stylist.

To Autumn retains classical iambic pentameter. For rhymes, however, Keats chose a complex scheme that splits its aural harmony across odd-numbered sequences. After an ordinary Shakespearean beginning (abab), each stanza introduces cde and finishes with dcce or, in the closing stanza, cdde. The cc/dd couplet achieves the “pounce”, as Keats put it, of a Petrarchan beginning (abba), but in a better spot for emphasis – just before the end. When the “e” reappears in the last line for only its second showing, it’s like the soft voice of an old friend.

The result is a supple and forgiving structure that allows us almost to forget that the poem rhymes at all. The ease on the ear contributes to its more modern sound, coaxing contemporary readers accustomed to free verse into accepting its formal precision. The poem lulls the reader as surely as drowsy Autumn on her furrow.

Inspired by To Autumn, I wrote a Keatsian sonnet of my own. In To Winter, I borrowed an approximately Keatsian prosody, and sought to respond to the harvested and snow-clad cornfields of my western Massachusetts town. Mine shifts the final couplet slightly, running abab, cde, ccde.

I wrote it years ago, but it’s since come to represent for me the next step from the incipience of autumn, into the fact of winter, the inescapability of it. Winter in New England has its own beauties, its own sere music.

… Once despoiled,

The exhausted fields give freely what is left:

Pockmarks of fallen seed on the dirt track;

Black twigs stained by berries; the dead spines

Of grasses, kernels clinging still. Now cleft

Of summer’s yielding fruit, but handsome yet,

These rolls of land unconscious of their lack

Lie bathed in sparkling breezes cold as wine.

In writing it, I remember, I had the extraordinary experience of the lines of the final stanza rising in my head of their own accord as I walked through town. We age, we give birth, we fade away; we are, in one sense or another, reborn. I like to think that Keats himself, that gentle and brilliant spirit in life no taller than I am, was walking the streets beside me. Without paper, I was forced to memorize the closing lines:

Let footsteps lead away, nostrils confound

The smell of soil with factories and cigars,

The soul in school be tutored to propound

Basest convention, and in sordid bars,

Shy of the most, learn to accept the least –

Still the land will lie silent in the wind,

The heart be drawn here ineluctably

Among the searchings of the many beasts,

A landscape noble, poised after the feast;

Alluringly familiar to the mind,

Its riches still as endless as the sea.

Naila Moreira teaches at Smith College and has been writer in residence at the Shoals Marine Laboratory in Maine and Forbes Library in Massachusetts. Her poetry chapbook Water Steet (Finishing Line Press, 2017) won the New England Poetry Club 2018 Jean Pedrick Prize, and her middle grade novel The Monarchs of Winghaven debuts from Walker Books US in 2022. Her poetry, fiction and nonfiction have appeared in literary journals including Terrain.org, The Cider Press Review, Connecticut River Review and others. She holds a doctorate in geology and has worked as a journalist, environmental consultant and aquarium docent.