By GRACE SEGRAN

I tucked my hands into the pockets of my cardigan and pulled it around me in a hug as I set out for my walk. The sun was low in the west, the air nippy. I wandered into Central Square just as the City Hall clock above me struck seven. Crossing the street, past the noisy tavern on the left of the sidewalk, and people enjoying conversations and dinner al fresco on the right, I arrived at Rodney’s. The bookstore is an institution in Cambridge, MA. It sells used and rare books with a fast-changing inventory. I made a beeline for the New to Rodney’s table in the center of the store.

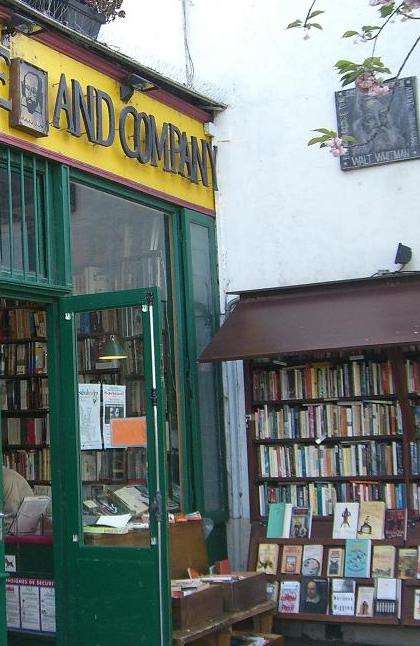

Rodney’s reminded me fondly of the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in the Quartier Latin in Paris, where two decades ago Raja and I used to go after our leisurely Saturday morning café au lait and oeufs sur le plat. We sat on comfy well-worn armchairs and read books from the dusty oak shelves, inebriated by the mustiness of the place. On a beautiful spring or fall day, we took the books outdoor to the sunny benches, or sat in the shade on the grass in summer.

Perched on a display stand in the middle of the Rodney’s table was a hardback copy of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. Raja would love that, I told myself as I reached for it. We’ve got several copies on the shelves at home already, including some vintage ones culled from bookstores all over the world. How he loved that meditative, gentle book of heartfelt personal prayer. As I put it back on the display stand, I looked over and there he was three yards to my right with his back to me, browsing in his favorite business management section.

I froze. Stunned.

My beloved Raja. South Indian complexion. White hair. Dark-rimmed nondescript glasses. Full white beard. Chinos underneath navy-blue sports jacket. Unbuttoned white shirt collar peeking above the jacket. Head bowed, looking at the hardback copy he was holding with his left hand while he flipped the pages slowly with his right, pausing to read certain parts.

I didn’t know what to do, what to think. I had thought about such a moment since he died four years ago. I don’t believe in ghosts or visitations. But, hypothetically, what if I saw Raja again? What would I do? How would I feel? What would I say?

His hair was full and tousled, probably rearranged by the wind outside. I’d always loved it that way because it made him look vulnerable. It would be at about this length that I would tirelessly persuade him to get a haircut. Good grooming, I’d say. It was so hard to get him to get one. I don’t know what his problem was. My theory was that it was hard work for him to sit still for the entire time, doing nothing. He would go to Helen’s for a haircut if we were in Singapore. Only she knew how to do his hair the way he liked it. He didn’t like the razor to be used to tidy up the base. But when we were not in Singapore, which was most of the time, I did it for him.

I caught myself staring at the man for an extended period of time. Better move away from the center table. I decided to move towards the street windows where I could observe him in full view. I went past Motorcycles, Aviation and Nautical, and stood in between Graphic Novels at the end of the row and the Classics on low shelves in front of the poster printing counter. I was now ten yards from him and I could see his full profile.

The resemblance was astonishing. Down to the slight paunch he had developed in his middle years. Raja was very thin as a child. There was barely enough food to eat at home and he regularly went to bed hungry. His mother often gave the children her portion.

Married to Raja for over thirty-one years and having known him since I was five and he was six when we first met in Malaysia, I knew every detail about him. Standing between The Astonishing X-Men Omnibus (Hard Copy) on the left and Henry James’s The Aspern Paper on the right, I began to notice differences. This man had on sneakers under his chinos. That would be a faux pas for Raja; he would have had on his casual Clarks lace-ups for going to town on a weekend. He was particular about his shoes. The first pair of shoes he bought after he started working in 1980 were a pair of suede oxfords by Clarks. They were brown and cost RM36 ($5), which he had to save several months for. That was a lot of money in those days, especially since most of his salary went to supporting his mother and sister back home. But he loved those shoes and reluctantly replaced them only when they were threadbare.

From my new vantage point by Dying, Aging and Vegan, now at the same table opposite the man, he looked somewhat shorter than what I remembered Raja to be. About two inches shorter.

That made him the same height as me. Did that mean we would now see eye to eye on everything? What would it be like to live with a man who agreed with me all the time? I’d hate that, I thought. I liked some dissent, some variance, because that’s what made us us. He took his soup lukewarm; I liked mine steaming hot. When I felt we should put in a bunch of money while a fund was selling low, he said we should do it regularly over time and reap the compounding effect. Dissent made us make better decisions, kept me in check and accountable when I was impulsive. Our differences made us stronger.

Despite the variations in the man’s appearance, the setting was certainly right. A secondhand bookstore Raja would have loved to spend hours in. He was drawn to big, heavy hardcover books, a quarrel we often had when it came to packing for a trip. For a week-long hiking trip to the Malvern Hills, he’d have a jute Sainsbury’s shopping bag packed to the brim with his books sitting in the doorway even before our luggage made it downstairs. I’d have just one book in my purse, which I left behind when I finished, hoping to pick up another when we got to the bookstores in the country.

Why so many books? I’d ask him. You never know, he’d say. The long evenings when it rains. Or I finish what I am reading before the holiday ends.

Bookshops or charity shops with a book section were pit stops wherever we went. They were also a good place to leave Raja when I wanted to explore the rest of a town, though then we often come back to London with two Sainsbury’s heavy-duty shopping bags full of books.

Imagine our delight when we visited the UK in 1979 for the first time and discovered secondhand bookstores. Not just a couple, but everywhere. Floors and floors of any imaginable title in bookstores like Foyles in Charing Cross, and Hay-on-Wye in Wales, a town in which every shop is a bookstore, punctuated only by cafes for refreshment and to rest tired legs from standing the whole morning in front of bookshelves.

Back in Rodney’s, I caught myself on the hardness of the present, embarrassed by the intrusion of memory. We were a long way from Shakespeare & Co and Hay-on-Wye. Yards away, the man’s pair of worn sneakers and shorter height betrayed the conspiracy. I watched the man with the tousled hair and white beard make his way across the old oiled boards of the bookshop. The stirred-up lifetime of memories began to ebb away.

I stumbled out of the store and back into the chilly air, just as the minute hand of the City Hall clock moved deftly to the number one.

An essay version of this dispatch won First Prize in the Memoir category of the 2019 Keats Literary Competition.

Grace Segran has been a journalist and editor for 25 years. She lived and worked in Asia and Europe before settling down in Boston, MA six years ago where she discovered creative writing at GrubStreet. Her personal essays have been published or are forthcoming in Entropy, Pangyrus, Woodhall Press’s anthology Flash Nonfiction Food, and elsewhere.

Image by Joao Araujo on Flickr.