One might ask: “What is this ‘new’ writing in the Arab World?”

Is it a “new generation” of writers? Is it an unprecedented form of writing? The new writing that this essay wants to explore has nothing to do with the age of the writer, nor does it claim that “new writing” suddenly dropped—rootless and without precursors—into the vast space of literature. Rather, “new” writing is an evolution in the techniques of the literary form; in the themes and subjects that correspond with societal change in “real-time”; and in the relationship between the writer, the “cultural authority,” and the official cultural sphere designated by governments and institutions. “New” Arabic writing is also the result of a struggle between the writer and his exploding surroundings.

An offshoot—and departure from—the “old”

A writer cannot claim to be completely separate from and untainted by his society and cultural history. The “new” is born out of the old, and successful experimentalism necessitates the mastery of older forms. The legitimacy of experimentalism depends on a clear underlying intention, and it is only through such clarity and mastery that experimentalism can be truly subversive. Experimentalism is not a “shot in the dark.” It is not “practicing” the form but exploring its potential: it is the expression of artistic intention underscored by deep artistic knowledge. The experimentalist understands, comprehends, and intends the techniques adopted and the forms utilized. The space for experimenting is created by a refusal to stay within rigid definitions of genre, the monotony of a clearly defined structure, and by being unafraid to cross boundaries and to connect with other arts.

The fall of romanticism

The modern-classical Arab writers, as represented by Nagib Mahfouz, Abdel-Rahman Munif, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, and Suheil Idriss, wrote mainly in realist and romantic veins. They addressed themes of liberation and progress because they were rooted inal-Nahda, the “Arab Renaissance” at the beginning of the 20th century, which catalyzed the era of anti-colonialist nationalist upsurge during the ’50s and ’60s. These writers were also bound by a paradox. They possessed both an internal (subtle, undeclared, but discoverable in their literature) admiration of the West and its accomplishments of material progress, order, and state-building and an external (declared, outspoken) anti-colonialist national liberation drive that fueled their aspiration to independence and sovereignty. This aspiration has not yet been realized, but has rather stumbled in the opposite direction. These successive defeats became the womb of today’s “new writing.”

The defeat, the retreat

In an era of inherited defeat and fragmentation, an era where hopes collapse and fall prisoner to the ever-rising walls of poverty, injustice, oppression, tyranny, colonization, occupation, and interventionism, the “new” writers, the experimentalists, retreat to their own selves as the only guaranteed, liberated space. It is from there that they launch their literary attack on the outside world.

“New” writing walks among the collapsed and depressed, the sacred statements of the past (unity, liberty, a better life) torn to shreds by the sharp teeth of the modern world and its power structures. In search of meaning, the “new” writers withdraw inwards, to a space where they can contemplate and write, or get angry and write, or raise questions and write. New writers seek to engage “the whole”—overarching social/political/economic conditions—and the limits of the existential, but from the starting point of internal conflict: questioning, premonitions, losses, and defeats.

Though today’s experimentalist writers may engage some of the language and perspectives of modern-classical writing, such as the stories “A House of Flesh” and “Little Bird on the Telephone Wire” by the renowned Yusuf Idris, unlike their predecessors, “new” writers do not aim to preach, build hope, or find compromises. They have departed to a new land of broken hopes and shattered dreams. After climbing the hill of hope and progress forecast and described by the previous writing tradition, they find themselves overlooking torched fields.

Arabic “new” writing and the institutions

In the wake of the departure of colonial powers and the rise of post-colonial Arab regimes, the gatekeeper of Arabic letters has been the government and governmentally controlled institutions. These institutions are isolationist by definition. The government thrives on control; it marginalizes those outside it and combats their projects. It assembles itself around the same “values” it claims to confront: nepotism, sectarianism, and other types of factionisms.

At the turn of the 21st century, a new institution entered the literary playground to compete with and supplement the power circle of Arabic regimes: the institution of “the market” as represented by “the era of the novel.” The emergence of flashy, generous prizes, mainly financed by the oil- and gas-rich countries of the Arabian Gulf, set the pace for writers: a mass exodus to the novel occurred as this genre became the literary commodity of choice in the publishing world.

The institutions of governments and markets do not readily acknowledge “new writing.” One reason might be that certain forms of new writing have exposed the mediocrity of institutional “products” and are a threat to its pitiful political and social traditions. The writers of official institutions must acquiesce to the long list of censored topics: the holy trinity of religion, sex, and politics. Commercial writers have managed to break the taboo on sex, but in such a way that renders it artistically obsolete. It is the scandal that they seek, the sales, the stardom, not the art.

“New writing” is not afraid of taboos. It challenges them rather than utilizes them and maintains its position at the margin, its rebellious, independent, and critical stance.

I have found “new writing” mainly outside the novel, in forms that lie outside genre conformity and market commodity, such as short stories and poetry. Not only in the Arab world, but on a global scope: in the short works of Jorge Luis Borges and Fernando Pessoa, the Invisible Cities of Italo Calvino, the Saharan Journey of Sven Lindqvist, the deep, rough poetry of Charles Bukowski, under The Tent of Margaret Atwood, and in the flash fictions of Lydia Davis.

Attempts to purge the “new”

During the Second Amman Short Story Conference (2010), many critics demanded that the short story form be purged of poetic language and that prose and poetry remain completely separate. This was in addition to an array of objections to experimentation with the short form, especially flash fiction; a demand to return to “plain” language; and a re-introduction of genre-based rules and demarcations.

At the same conference, a reading of my story “Penis Envy” was met with shouts of objection. The story, from my collection The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, explores various layers of patriarchy through the tale of a university professor (who is also a consultant to the story’s “Deified Leader”) who sexually harasses his female students. “This is not what university professors are like,” shouted one university professor, while other writers thought the story was “obscene” and “not suitable for public reading in a literary conference.”

One can imagine what is it like when (“institutional”) critics and fellow writers demand sterilized literature, in form and content. One result is the further challenging of these perspectives, increased engagement with the troubling issues of modern existence, and the investment in literary progress and renewal.

Experimentation: evolution; the Arab region in fast-forward

In literature, as in all arts, experimentation is the path forward, toward new forms. Of course, what is “new” now becomes, as time moves inevitably on, part of the classical. New forms and themes exhaust their potential as time, society, history, power structures, and language change; thus new ways of expression that correspond to these new challenges and transformations must emerge.

And how rapid the changes have been in the Arab region. In less than 150 years, the region has seen the fall of centuries-long Ottoman rule; the first World War; European colonialism and the division of the region into states by the colonial powers; the rise and fall of the “Arab Renaissance”; the establishment of a Zionist settler-colonialist Israel; the rise of oppressive Arab regimes; the defeats of al-Nakba (1948) and al-Naksa (1967) in Palestine; the rise and fall of Arab Nationalism and its hope for a unified prosperous modern Arab state; the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982; the establishment of the Khomeini regime in Iran and the long Iran-Iraq war; the rise of Islamism and religiousness among wide swathes of the population; the proxy-war in Afghanistan and the rise of the Mujahedeen; the rise of the petrodollar and the influence of Gulf regimes; the first Gulf War; the second Gulf War and the US occupation of Iraq; the rise of sectarianism and other types of fragmentation; the Arab Spring; the collapse of some of Arab pseudo-states such as Libya, Iraq, Yemen, and Syria; and the rise of the so-called Islamic Jihadists and their horrific practices; all in parallel with the rapid transition of mainly self-contained, self-sufficient, and interdependent rural/Bedouin communities to the highly dependent, malformed, pseudo-urban clusters of the high-tech, ultra-consumerist world.

This is a simplistic, superficial fast-forward view of an era so bloody and complex that it lies heavy over the consciousness of all citizens. As the writer himself transforms, engages or disengages, attacks or withdraws, so does writing itself, so does language. The search for meaning amidst cataclysmic change and in opposition to restrictive institutions is what is “new” in contemporary Arab writing, something that cannot be found in the commercial, institutionalized forms.

Pioneers: “new” writing as a continuum

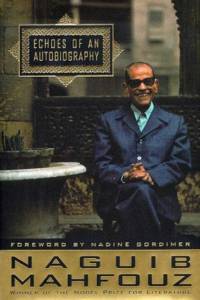

To list the names of the pioneers of “new writing” in the Arab world is to do an injustice to others, but I will take that risk in order to shed some light on a literature so unrepresented in the global literary scene and so neglected (rather than lost) in translation. Zakaria Tamer, Mohamed Zafzaf, Mohammad Khodayyir, Haidar Haidar, and Mohamed Makhzangi are members of a regiment that introduced new sensitivities, new styles, new techniques and—to an extent—a new language in literature. From the dystopian to the contemplative, these writers have defined a new artistic effort that today’s writers are now pushing forward. Naguib Mahfouz himself, the great novelist who concluded his life not with a novel but with six short story collections, approached new forms in his masterful collection of flash fiction, wrongly described as non-fiction in the West because of its name: Echoes of an Autobiography.

The past, the future, now

I take “newness” to be an expression of both a writer’s interest in innovative artistic forms and his engagement in current affairs. For the new writer, “now” is the condensed point where the past meets the future, a collision of different sensibilities in the boiling pot that is today’s Arab world. It is a mere coincidence that I, a writer, happen to be here at this point in time, and I take it to be my challenge to engage this point on different levels and from various perspectives. Engagement with the coincidence of existence at this particular collision point in Arabic life, a point burdened with all the unaccomplished hopes and dreams of the previous generations, with rapid transformations, with the need to question a stagnant past/present and contemplate a transition for the present/future, this is what I call new Arabic writing.

Hisham Bustani is the author of four collections of fiction and has been featured internationally in publications such as Poets & Writers, the German magazine Inamo, and Britain’s The Culture Trip.

Image 2: From “What I Create Will Outlast Time” by Rafik Schami, calligraphy by Ismat Amiralai, Interlink Publishing, Northampton, MA. Reproduced by permission.