The walk to the outhouse was some thirty yards—across the bare back yard, past a fishpond filled in with sand after a turkey had drowned there, and through a gate at the garden fence—to a little unpainted hut behind two salt cedar trees. It was quiet inside, the murk tempered by sun slanting in between weathered boards. The hush was lovely—breezes outside cocooning the silence inside. When I was seven years old, I discovered solitude there. And the pleasure of staring. At men. In lieu of toilet paper, our outhouse was stocked with last year’s mail order catalogs, with pages of men’s underwear for me to hover over. I was several years shy of learning about sex—from a Roman Catholic booklet so primly informative that I pictured two fully clothed adults just returned from Sunday Mass, facing each other in straight-backed dining chairs and holding hands while some kind of mystical transference occurred between their covered laps. Though I had been to confession, I hadn’t yet discovered that my body could be an instrument of sin, of shame. Somehow, I had absorbed the need for privacy, for keeping the secret of my mail order fascination.

In this regard, the child in the outhouse was well-trained. The farmhouse where he spent his days, the surrounding fields, the parents who raised him, they too harbored a cumbersome secret. They trained him in the habits of silence. Before he had the words for what it meant to look lovingly at the torsos of men, the briefs they modeled for Sears, for Montgomery Ward, he was rooted to this place, to its silences.

An aerial view of the Meischen family farm (circa 1980s)

Midway Station marks the nearest major intersection—where Farm to Market Road 624, coming west out of Orange Grove, crosses Texas State Highway 281. Buses traveling south out of San Antonio once stopped here, just south of the Jim Wells County line, in what would have been Mexico had Texans conceded the Nueces River as their southern border. From Midway, follow 624 east for approximately two miles. Ahead on the left, at the top of a low rise, sits the one-room Dilworth community schoolhouse, to the right the community cemetery. Just short of the graveyard a county road cuts south through the brush country toward Aqua Dulce Creek, a mile drive with caliche dust pluming behind. Little traveled, the road marks the farm’s eastern border, trees along the dry bed of the Agua Dulce its ragged southern edge. The farmhouse is set back off the county road, accessible by a narrow lane.

It is 1941, eight days into May, the stillness marked by sparrow chatter from the hackberries, chickens along the fence line, breaths of breeze at the open windows. Inside the quiet house, a ringing phone. Lillie Bruns Meischen, age forty-five, mother of three, picks up, listens. She cries out then, and her sons come running from their chores outside. What she tells them will change everything.

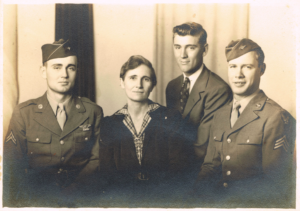

At some point during the previous year—looks to be summer from the shoes and clothing—the farm’s inhabitants posed for the only photograph to survive showing all five of them intact. Herbert George Meischen, his wife Lillie, twin sons Wilton and Wilbert, seventeen when the shutter clicked. And the youngest, Elwood, who would become my father, fifteen-turning-sixteen in 1940, though he looks younger beside his brothers; their father dominates the group at well over six feet.

A number of years back, I borrowed this photo from my father and made a high-resolution scan. I study it sometimes for clues. Who is Herbert Meischen? What is it that bides inside him, patient but deadly, so powerful when it wakes the following spring that he will be removed from the farm, taken away to San Antonio, to what was then called an asylum. A place so poorly managed that the first night of his incarceration, he will get his hands on a razor blade and open his wrists.

The photograph was taken in Orange Grove, where my father and his brothers attended high school. In the background, across the highway, train tracks. Just behind the posed group, gas pumps, a Royal Crown Cola sign, a covered driveway, a pickup truck. This is the Roth filling station, owned by Herbert Meischen’s niece and her husband. It stayed there, little altered, through the years when I was growing up, an anchor for me, a place where this family paused to let themselves be preserved on film, a place where I might almost see them breathe—where, looking back, I might reclaim the fleeting sense that I, too, am one of them, at home among kin.

I concede that I’m not in the photograph. Simultaneously, I insist that I am. Before I took my first breath, I was shaped by the man I contemplate, by his wife, his sons. They don’t know what’s coming. I do. Hindsight makes this moment part of me. Hindsight inserts a suicide they don’t know will happen into the moment of the photograph, into me. Who I am does not begin with my first breath three days before the end of 1948. Who I am begins on the night of May 7, 1941, with a razor blade. Who I am begins with my grandfather’s final breath.

From left: Wilton Meischen, Lillie Bruns Meischen, Herbert George Meischen, Wilbert Meischen, Elwood Meischen.

He stands at the center of the group, a step or two closer to the camera, looming larger, taller against those who flank him. To his immediate right, in plain black pumps, a simple print dress with white collar and white belt, my grandmother. Short dark hair, no evidence of makeup: a farm wife dressed for town. To her right is Wilton, with his sleek, shining hair—open-collared shirt, suspenders, white shoes—the only male in the photo not wearing a hat. Wilbert, his twin, stands just behind my grandfather’s left shoulder, his face turned due right, his right foot turned as if the shutter caught him mid-step. To his left, Elwood, youngest of the gathered Meischens. Like Wilton, his shirt collar is open at a rakish angle. Like Wilton he wears suspenders and white shoes.

My grandmother squints into bright day. No one smiles, not even Wilton, though his brows arch and he alone hasn’t compressed his mouth into a line. He has the look of a seventeen-year-old who knows he’s good looking and would rather not ruin it by pretending he’s graveside or in church. My grandfather and my father face the camera beneath the brims of hats—a dark band of shadow masking their faces from the nose up, darker shadow where the eyes would be. Or does the imagination supply eyes where the camera sees none?

I look and look. I see only masks. I hear a whisper of something unsaid: I will not be known.

Lillie Meischen and her sons in 1942, the year after Herbert George Meischen’s suicide. From left: Wilbert, Lillie, Elwood, and Wilton Meischen.

My grandmother cried out when they told her that her husband had killed himself. This is the one fact I know from that day. What came after has been lost to the silence that took hold from the moment his suicide was spoken. Her sons adhered to the hush, and when they married, their wives followed suit. When children came along, when we got old enough to wonder aloud about our missing grandfather, our mothers took us aside, each child in turn, and said what had happened. I hear the hushed voice—He took his own life—or words to that effect, a simplified version of the facts, edited for the curious four-year-old. Then the mothers said what needed to be said, ensuring further silence: We don’t talk about this in front of your father.

Much of this is inference, of course. I know that my mother told me the facts about my grandfather, that she said the manner of his death was not to be mentioned in my father’s hearing, that in many silent ways as I was growing up, my sister, my brothers and I learned the Meischen family version of the fourth commandment: Do not disturb your father. I remember a rehearsed quality to what my mother told me, a quality of ritual. I have always assumed my sister and brothers had been subject to the same rite, that my aunts initiated my cousins in a like manner, eliciting their promise of silence.

Elwood and Valerie Meischen (center) and their wedding party, June 5, 1946.

My mother was raised on a farm east of Orange Grove. Born Valerie Morgenroth, she was old enough—thirteen—in the spring of 1941 that no one kept the news of Herbert Meischen’s suicide from her. Five years went by. On June 5, 1946, Valerie married Herbert’s youngest son Elwood and moved to the Meischen family farm. Children, anniversaries, crop cycles marked the decades that followed. On June 12, 1979, Elwood’s mother Lillie Meischen died. My parents lay awake that night until dawn, my father, awash in memories, talking to my mother—their bedroom softly aglow from moonlight at the windows, the gray of dawn hesitating, brightening into the chatter of sparrows. They moved their conversation to the front porch swing—so much unsaid to say between them.

Daddy was fifty-four then; he’d been just short of twenty-two when he and my mother said I do. Growing up, we knew—Judi, Larell, Vance, and I—that our parents were absolute in their commitment. They loved each other without reservation. Not with the easy public words that became the mark of a later age, and not with the poisoned terms of endearment that have marked other family marriages. No. Elwood and Valerie Meischen built their love out of the work, the years’ accumulation of what they did for—not to—each other.

From left: Family portrait: Elwood, Larell above and Judi below, Vance above and the author below, Valerie.

My parents spoke often. Many nights when I studied late, I heard their voices, muffled, behind the closed door of their bedroom, my father confiding in my mother, my mother confiding in him. Still, the night after my grandmother died, when Daddy turned to Mother and spoke of his life growing up, he broke a silence of almost forty years. This was the first time my mother heard him put into words what mattered most: his missing father. The years of work and hardship alongside his missing father. His missing father’s voice inside the farmhouse; his missing father’s life outside the farmhouse in field and town. The blunt force of his missing father’s death. And Daddy’s accumulated grief, the words begging to be given voice.

(I have called my father Daddy all my life. I’m aware of the truisms—that Daddy is a child’s moniker, a relic of patriarchy, a retrograde Southernism akin to wedding thirteen-year-old cousins or growing geraniums inside of ruined tires. I can’t help it. Everything he means to me lives inside the name I’ve always called him. Now that he’s gone from this life, these two syllables are especially dear to me—the feel of them at the tip of my tongue, the sound of them released into the air I breathe.)

Daddy’s chair was a ponderous reclining rocker that occupied a corner of the living room—all shadows, a space rarely entered during daylight hours. This man napped in his chair. He presided over televised sports there. He sat with us during Gunsmoke, Wagon Train, Rawhide, Bonanza—the steady diet of westerns we consumed as a family. Many times, too, my father came to his chair, rocked back, and succumbed to one of his moods, his face a mask of wordless hurt.

Life went on around him while he sat there. Mother would have walked by, going back and forth between the kitchen and the bedroom they shared. Or she might have been at her sewing machine, in a corner of the dining room, with just a wall between them. The dining windows were often open to the breeze, the sounds of farm life drifting into the house—hens cackling as they scratched for worms out back, cows mooing where they grazed, my brothers, my sister and I, at work or play, calling out to each other. Still, when Daddy went to his chair, he took silence with him.

My mother told me about my grandfather’s suicide and, years later, about her remarkable conversation with my father the night his mother died. But these were rare moments, brief forays into difficult territory, quickly released to the prevailing silence. As a child, I readily absorbed the tacit understanding that certain things were not mentioned. This silence carried the weight of shame, the weight of Church teaching. Catechism taught us that suicide was a mortal sin, that a mortal sin had to be confessed and absolved before the perpetrator could re-enter a state of grace, that suicide would be eternally unforgiven. Consider the verb in the common expression commit suicide. To commit an act is to perform it knowingly, premeditatedly, in full control of one’s faculties. To commit suicide is to choose damning sin.

To violate precepts governing what can and can’t be done with the body incurs damnation too. During my years of looking at mail-order men’s underwear, sin played no role. Four years later, though, entering puberty, I discovered temptations of the flesh. When I was fourteen, I let my hands stray beneath the waistband on a pair of tangible briefs.

A bedroom in town, a summer breeze, the occasional car driving by out front—a wash of headlights in bands through Venetian blinds. An invitation. Tentative touching. And then more. Touching and touching and touching. Release. This time the guilt was crushing—but also short-lived. Without thinking, I found a space separate from my sense of myself for the shameful needs my body proved unable to resist. There was ample room in the silence that framed my family story. If suicide is expunged from the record a family constructs with words, did it really happen? If proscribed sex is boxed up in the confessional, maybe I could leave it there, with a shadow version of myself who wasn’t really me.

My grandfather was not a Catholic. He and my grandmother—my father, too—were members of a small Protestant parish affiliated with the United Church of Christ. I have no idea what Protestant doctrine of the time had to say about suicide. I do know that the Christian churches of my youth, Catholic and Protestant alike, were prescriptive and judgmental, parishioners inclined to condemn any act of radical nonconformity. With suicide they were caught between judgment and sympathy. Small surprise, then, the unequivocal silence that followed in the wake of my grandfather’s death, all of us tongue-tied by dueling impulses.

And while the silence bothered me, while I wanted words to explain my grandfather’s death, I let the stillness be. There is a curious relief in not speaking of the difficult thing even as you long for the release of naming it. A curious relief, too, in avoiding difficulties of the self. A boy who learns to enclose a missing grandfather in invisible parentheses can learn to edit himself for others. A family that doesn’t acknowledge grief beating at the heart of things might be perfectly suited to embrace the girly boy in their midst and not see the gay in him.

I didn’t have the words; that would take years. But I knew I was different. My parents knew—my brothers and sister. Cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents. We were experts, though, in not knowing what we knew, in not putting words to what was right before our eyes.

Oddly, our silence was wrapped in sound. We Meischens are talkers. On Christmas Eve, when I was growing up, we gathered at Grandma Meischen’s house—her sons and their wives, her nine grandchildren, all of us in a modest living room, the furniture crammed with adults, children overflowing onto the floor. All of us exclaiming at once over a just-opened gift, all of us rising to sing.

O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum

wie schön sind deine Blätter.

Du grünst nicht nur zur Sommerkeit,

Nein auch im Winter, wenn es schneit.

Three generations removed from the Germans who’d landed at Indianola, my German was fragmentary at best. Such comfort, though, in syllables that meant family, such comfort in my father’s baritone, in memorized sounds emptied of meaning—and brimful of kinship.

Between carols and verses from the Bible, side conversations erupted at random. Aunt Madeline’s recipe for Waldorf salad, a new pair of heels my mother had allowed herself, a deer hunting excursion planned by the men—all were grist for the mill, with the children yammering full throttle between shushings by our parents. The joke about Meischens is that we talk in one another’s presence, that listening is optional.

Outsiders, newcomers, have thought us rude. And perhaps we are. But sometimes gathered with my family, the words flowing—I dropped out of myself, out of the alphabet and beneath meaning, into pure sound, a swirl of voices cocooning me. The wordless message of family—that I was one among these. If only briefly.

My parents regularly hosted holiday meals for the extended family. After we’d eaten until we could eat no more, the men were ready to sit back and watch football. Perfectly inept at team sports of any kind, I had developed a special immunity to the televised spectacle. While the men cheered and scoffed and carried on, I adjourned to the kitchen. Pitching in, washing up, refrigerating leftovers—I was at home among the women. Again, it was the voices, the way my mother and my sister, my aunts and my grandmothers absorbed me into their company. The blunt truth is that no one paid me any mind. Not that I was ignored, but my presence drew no unwanted attention.

When I was ten, my mother showed me how to make basic Texas chili con carne. Even now, I can hear the sound of a chopping knife against our old wooden cutting board, onion sharp in the heavy Gulf Coast air, the sting of onion tearing my eyes, the scent mellowing as it sizzles in butter. I grip an old wooden spoon, its handle charred, and stir chili meat into the browning onion. I sprinkle chili powder, inhale spicy steam above the bubbling pot. I stir in tomato sauce. I raise the spoon, blow to cool the pungent mixture, bring the spoon to my tongue.

In no time I was a fixture in the kitchen, frying and cooking and baking—fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, cookies and brownies and cakes. I could disappear into the magic of devil’s food batter, the perfect layer cake, seven minutes over a double boiler to produce airy peaks of seafoam frosting. One evening at the lake, after hours of skiing, our host for the occasion paused before forking into a second slice. Someone had told him I’d baked the cake he was eating. Like all my father’s friends, this man loved raucous humor. Like my father himself, he wouldn’t miss a good opening. Grinning in my direction, his teeth flecked with bits of chocolate, my father’s friend winked at me.

“If you weren’t so ugly,” he said, “I’d marry you.”

No one laughed. The unsayable had been said.

My mother tried once.

I was twelve at the time, smack in the middle of junior high. Loud and flamboyant, I had stumbled upon a two-pronged approach with boys my age. My jokes, my clowning around, allowed them to laugh without explicit ridicule. My short fuse inspired caution. If they needled me and I lost my temper, teachers would converge and all of us would pay.

Mother and I were sorting laundry. Easing her way, she remarked that it was okay I didn’t participate in organized sports. No need for me to be out on the field with the guys. There is always a but in this kind of conversation between mother and son. Here was my mother’s.

“Why not take an interest?” she said. “Pay attention to baseball and football. Know the rules. Follow sports on television.” Why? “Because,” Mother said, “that way you’d have more friends.”

I don’t remember what else was said. I do remember what I thought: I don’t need more friends.

It was an awkward conversation, the subject quickly put aside. We simply didn’t have the tools. Besides, memorizing sports trivia would have been a fool’s errand. The boys my age would have seen through such a con. The trick lay in not saying.

My mother died on a Saturday evening in May. It was 1995, and the next day was Mother’s Day. The year that followed was extraordinarily difficult for Daddy. He was not the kind of Texas man who turns helpless with frying pan, dust mop, laundry; he was perfectly capable of feeding himself, of keeping his house, his clothing clean. It was the empty rooms he couldn’t bear. Several times that summer he spoke to me of his life on the farm after Mother died. As so often before, he would drive to town, sit down to cards or dominoes with old friends in the VFW hall. There was comfort, he said, in company, but afterwards he drove home alone. To an empty house. Sometimes, when he closed the door behind him and heard the silence, tears came out of him—bitter, painful tears.

I felt close to this man in the months after Mother died, an understanding between us that he could speak his grief, that I was not afraid of tears. Since the end of my marriage a year before, he’d known that I am gay, and though he would not speak of it unless I forced the issue—and then with anger—he’d managed to set aside this knowledge and love me anyway. And so, one summer afternoon, I asked him the question that had been pushing to be spoken since first I heard the bare facts of my grandfather’s death. I was sneaky with my timing, holding off until the end of a visit.

“There’s something I want to ask you about,” I said, my hand at the door. “If you don’t want to talk about it, I’ll head home and you can forget I asked.” A pause. “I’ve always wondered about my missing grandfather. If you could talk to me about him, I’d like that.”

“Might be difficult,” Daddy said. But he didn’t say no. Then, ever the cautious son, I got in my car and drove back to Austin.

My next visit to the farm, we sat at the picnic table out back, and my father broached the subject. He started with a ringing phone. My grandmother answered and took the news. She gave a great cry. Her sons came running. Further, Daddy said, he knew of another bad episode, one that had occurred years earlier, before Herbert and Lillie Meischen pulled up stakes from the Garfield community west of Yorktown, Texas, and moved to the farm in Jim Wells County. This move took place in 1929, shortly before Daddy’s fifth birthday. What he remembered, many years later, is that his father had been absent from the Garfield farm for an extended period of time. Days? Weeks? Daddy didn’t know, only that for a stretch his father was not there, that he was in an asylum—or some such euphemism for where the broken were taken when their families could no longer handle them.

In the summer of 1995, beside me at the picnic table in the back yard on the Meischen homestead, Daddy said he’d wondered if moving to the farm west of Orange Grove might have been his parents’ way of forging a new life in the aftermath of his father’s breakdown. It’s an all too human failing, this notion that a change of venue will fix what’s wrong with us, forgetting as we often do, that when we get to the place we are headed, we will be there. My heart breaks thinking of the hope, the strength of will, the work my grandparents put into their new life on Agua Dulce Creek. If it made a difference for my grandfather, the difference didn’t last. But my grandmother carried a well of personal strength wherever she went. She made a home for my father that lasted to the end of his days. She carved out a place for all of us. I feel the pull of it still.

Another thing Daddy said to me: If they’d had Prozac back then, maybe Herbert George Meischen would have lived to die of old age. So. Depression.

But why was my grandfather taken away? Was he catatonic? Aggressive? So hostile my grandmother feared for the safety of herself, her sons? And taken away how? Did they come for him—Was there a straitjacket? Or did my grandfather let himself be driven to San Antonio? Did he beg to be locked away?

I didn’t ask. I let Daddy talk. I assumed this would be the first of regular installments in a conversation so long in the making. But for the remaining twenty years of my father’s life, neither of us raised the subject again. Old habits take hold. They outlive necessity.

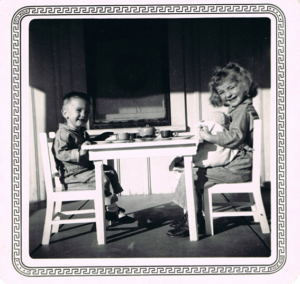

My sister Judi and I—eighteen months apart, firstborn child and eldest son—have always been close. In one of my favorite snapshots, we’re sitting on the front porch, ages three and four, at a little table our mother’s father built for us, having a tea party. As young adults we spoke about relationships, about the ways in which our values had diverged from the Catholic catechism, the small-town customs we’d absorbed growing up, though we never discussed our grandfather’s suicide or the silence we’d subscribed to. And Judi got a carefully abridged version of me—no mention of the sex I was having with men.

I do not wish to suggest that my grandfather was a homosexual, driven to suicide by self-hatred and repressive dogma, that I link myself with him in this reductive manner. What I am trying to say is that being gay—in denial and afterward—has often left me on the outside looking in, that I have felt a kinship with the grandfather I never knew—set apart from community, family, self, by an ineffable, unnamed something inside him. I have never been suicidal, but I know what it feels like to live a masquerade version of myself, to be at home but not of home. This has been the most painful experience of my life—feeling invisible among kin, a vital truth about me wrapped in silence.

Countless hours of my growing up were spent in Uncle Wilton and Aunt Madeline’s back yard, playing with my cousins and siblings. We had a swing set; we had monkey bars. We had expanses of carpet grass suitable for any hyperkinetic game that popped into our heads. One Saturday afternoon when I was twelve, my cousin Gary, four months older, stepped over a line with me.

I have long since forgotten the putative subject of our disagreement. It doesn’t matter. Gary was twelve going on seventeen. Gary was itching to knock a bit of the girly out of his cousin.

“Panty waist,” he might have said. “Why don’t you go inside? The Barbies are waiting.”

I don’t remember what I called him. Asshole? Bastard? Son of a bitch? What I remember is this: I let go with my mouth, and Gary backhanded me.

The pain pulsed in my jaw. The pain shot up my nose, singeing the corners of my eyes. The pain ignited me. For the space of an instant, I was pure rage. I lunged and locked my teeth into the flesh of Gary’s chest. I tasted sweat. I tasted blood. I ran howling into the house.

It was like that with the two of us. Beyond banalities of insult, we didn’t have the intermediary of words. And what about our fathers? What help might they have been?

Herbert George Meischen’s sons had been well trained. They were not going to specify what lay in the no man’s land between Gary, well on his way to being the badass black sheep of the family, and David, utterly inept at any and all of the signposts that said male, that said masculine.

A summer or so before high school, Gary and my brother Larell spent weeks insisting they be allowed to camp overnight in the brush country of a neighboring ranch. My cousin and my brother wanted to carry guns; they wanted to sleep under the stars; they were eager to be men. I didn’t care about guns or practicing a slouch I’d never be able to master, but I wanted to cook over an open fire.

We set up camp on the embankment of an earthen stock tank. I built us a fire. I cooked. I don’t remember what I cooked. What I remember is the feeling that I was useful, that I belonged. I want to say this outright: I was a happy kid, a benefit, at least in part, I think, of denial—my own denial, my cousin’s, my brother’s. The three of us ate and talked that night beside the stock tank, at home with each other as cousins, as blood kin, peacefully unaware of whatever inside any of us might run at odds with who boys were supposed to be.

We slept. I woke early and ambled a bit, soaking up the gray dawn light. Past a thicket of huisache, I stopped. Ahead, at the rim of the sloping embankment, stood my cousin, dick in hand, looking out over the silvery water, peeing. I stared—he never saw me watching—then turned and walked back to build up the fire for breakfast.

It’s embarrassing to admit, to see the words tapping across the page, but at the stock tank that morning—and in other unexpected glances—I liked what I saw, doubling the taboo of same-sex attraction by registering a cousin’s magnetism. I stored these glimpses—of Gary, of myself—in a bunker-strength compartment, knowing any hint would tear another hole in the family narrative. Shame and silence are so well suited to each other.

I don’t remember how it happened, but by the time I entered high school, my cousin—a year ahead in school—no longer bullied me, and I had learned to deflect the wisecracks he aimed at everyone. Years later, wondering how I sailed through high school unscathed, I arrived at my cousin’s presence. If any of the aspiring ruffians who walked the hallways with us, if even one of Gary’s blustering buddies had insulted me, harassed me, tried to push me around—Gary Meischen would have stepped in, fists raised. As for grades and studying—the kind of knowledge one might find in books—my cousin had no interest in these. When he got behind in geometry, he came to me and I helped him.

A cocksman in training, he bragged about his sexual exploits—and then turned small town expectations upside down. Gary refused to marry his pregnant girlfriend, and the girl stayed put during her pregnancy. My parents had an expression for unthinkable violations of the norm. It just isn’t done. But my cousin did. And then the girl did—not just by staying in town while her abdomen swelled. When the child was born, his mother kept him. She and her own mother raised him on the same streets Gary walked—his firstborn son, well into adolescence before someone pulled the boy aside and told him who his father was.

It occurs to me now that, although I’d learned not to tangle with Gary before he tripped on his own swagger, I felt genuine sympathy—even begrudging admiration—in the months after he refused to say I do. Honesty was my cousin’s real sin. He didn’t love the girl. He knew that marrying her would compound his mistake by saying I do to certain disaster. Turns out he traded one disaster for another.

By the time we were in our twenties, the few times I saw my cousin, psychic pain and alcohol released a floodgate of words. A beer or ten and Gary’s troubles came pouring out. I listened. But did I really? After a while Gary’s story was tiresome. At intervals I handed him bromides, all the while thinking that what he needed was a good therapist. Why didn’t I say so? Perhaps because by then I lived elsewhere, by then I was telling myself that I’d got out. By then I believed release had been easy as transporting myself to Austin.

In the spring of 1974, when Gary and I were twenty-five years old, I sat with him one Sunday morning on the steps of the drive-in grocery and ice service that had fallen to him two-plus years before when a sudden stroke felled his father. Gary was badly hung over that morning. The bags beneath his eyes, always visible during this stage of his life, had darkened like bruises. His hair was uncombed, face ashen, shoulders slumped, characteristic bravado conspicuously absent—no glint of irony, no words to needle me.

Rode hard and put away wet is the expression my father would have used.

“You look a wreck,” I said. “If you don’t take better care of yourself, just think. What’ll your life be like when you’re forty?”

“Oh, David,” he said, pitying me because I could see no farther than the nose on my face, “I won’t make it to forty.”

Gary Meischen was thirty-three when he died, coming home from a late night by himself at a club somewhere in Corpus Christi. He fell asleep at the wheel. His car sideswiped a freeway divider. He wasn’t wearing a seatbelt.

Here’s what strikes me now. At our closest, with Gary confiding in me, admitting—almost—a death wish, while I sat there and tried to talk him into a less self-destructive way of being in the world, we—neither of us—ever—put into words the specter of the shadow that haunted us, that has haunted every Meischen son since the day the phone rang and someone told our grandmother her husband had done himself in.

Here, let me come back to the word commit, to the conviction—everywhere in the world my cousin and I inhabited—that we choose who we are. That my grandfather chose to take his own life. That I chose—in the words I used in Confession—impure deeds with another man. That Gary’s personal choices had brought him to the brink. The wages of each choice was shame. The wages of shame: silence. No words to reflect on our grandfather. No words I might speak if I wanted to live in the circle of my family’s approval. No words Gary could summon beyond the bleak admission that he felt doomed.

Five years passed after my conversation with Gary. When, on June 12, 1979, Grandma Meischen died, six grandsons survived her, and we served as pallbearers at her funeral. My cousin Scott was twenty-five then, the youngest cousin. Being Meischens, we talked, both of us at once, with much interrupting, much repeating of favored ideas, in the midst of which, Scott and I discovered a shared tendency, both of us drawn to thinking about the things we’ve been told are off limits, to wondering why the limits have been set where they are. Scott brought up our missing grandfather—named him in words that I could hear. We talked about the unspoken rule that Herbert George Meischen not be mentioned in front of his sons, a stricture that had banished him from any talk among Meischen kin. Scott told me that as an adolescent, he’d entertained a darkly humorous fantasy. He walks into a Meischen family gathering—indoors, close quarters—waits for a low point in the conversation, then raises his voice above the burble of words: “He killed himself!”

He watches while aunts, uncles, cousins scatter for cover.

Here’s what I notice looking back. Scott’s story turned our grandfather’s suicide into a punchline. And this: We didn’t pursue the matter further, didn’t ask ourselves what kind of price we’d paid for our part in a decades-long silence, didn’t speculate aloud about how we’d been fathered by men who’d not spoken their own grief, by a code that privileged silence over truth, over any kind of healing.

Scott’s story has a coda. In March of 2015, I wrote and delivered my father’s eulogy. Daddy was the last of his father’s immediate family, the last Meischen before whom his father’s suicide was not to be mentioned. As a tribute to those who survived Herbert George Meischen, I specified the manner of his death and spoke of the strength my grandmother and her sons summoned just to go on. Afterwards, Scott’s son Michael expressed shock at the news of his great-grandfather’s suicide. It was an episode of family history Scott had never mentioned.

And this: Months later, I answered a call from my brother Vance, who’d been brooding over my eulogy, who wanted to say that by speaking publicly about our grandfather’s suicide, I’d broken the fourth commandment. Vance seemed to think I was trying to settle some kind of score with Daddy.

Seventy-four years had passed. Herbert George Meischen’s wife and sons had joined him in the family plot. No one alive might suffer grief at the mention of his suicide. Still, his grandchildren, most of us now grandparents ourselves, were willing to erase him—his name, his story, his life, his death. As all of us have applied this long-held disposition by not seeing, not naming the clearly gay child who grew up among us.

I am that child. I carry him inside me. Saying the truth about myself is the hardest lesson of my life. I am still learning how to do it.

In the Kodak snapshot of the tea party I mentioned earlier, I sit facing my sister, though we are not looking at each other—grinning instead toward the box camera our mother is pointing in our direction—a three-year-old and his four-year-old sister. Say cheese. Sixty-seven years later, 845 miles away, I hear our mother’s words, her voice, her inimitable self. We’re sitting on the front porch of the house the Meischens built in 1930, a year after their arrival. My father and his brothers grew up here. In one of the rooms behind my sister and me, our grandmother answered the most difficult phone call of her life.

Judi wears a grin that looks as if it sprouts from that endless source of good cheer children seem born with. My smile is less expansive, but I am clearly a happy little boy. On the child-size table between us, a diminutive teapot, two cups, two small plates. I’ll leave us here, with our lives ahead of us.

David Meischen is a Pushcart honoree, with a personal essay in Pushcart Prize XLII. Currently at work on a gay-themed memoir—Crossing the Nueces: Reflections on a Divided Life—Meischen lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with his husband and fellow poet Scott Wiggerman.

Photos courtesy of the author.