I was waiting at the top of the escalator, as we had agreed the night before by phone. The marble palace of the metro station Gorkovskaya, named after a Russian writer whose name means “bitter,” felt solemn enough for the occasion. I was peering into the face of every woman delivered by the moving stairs, as if each was a final product on a factory line reaching its destination. I watched their wandering looks, their wrinkles, the tensions of their mouths and speculated which one was my mother. Any of them could be.

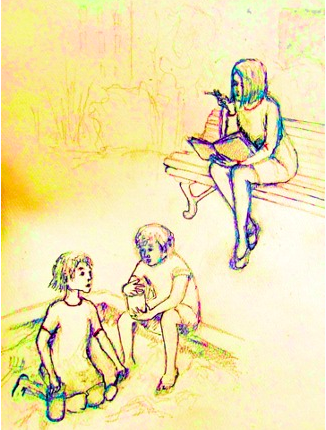

She had disappeared before I was two, so it was quite a labor to pull her face to the foreground of my mind from the weathered jigsaw puzzle of babyhood memories. I remembered a small, dark-haired woman with high cheekbones sitting on a bench in a playground. She had a cigarette in one hand and a book in the other. I was monitoring her presence from a sandbox where a girl, slightly older than myself, was telling me that the sand in her little red bucket was ice cream. Unable yet to say that I knew it was not, I surrendered. I took some in my mouth and chewed it slowly as it rattled in my ears. Absorbed by the book, my mother glanced at me and smiled. She was eighteen.

Shortly after that, my father’s parents “rescued” me from my mother and secured me in their home full of dolls, stuffed animals, and chocolate candies. I liked my grandparents, but I wanted my mom. I called her on a toy phone and begged her to come get me. She didn’t respond. Invincibly, I kept dialing the plastic disc and running to the door whenever the doorbell rang. Other people came. She couldn’t. She was lying face to the wall in her parents’ house, her bed unmade for days, mourning separation from her child. Were her parents consoling her? Did they plot to steal me back? Or had all four grandparents co-authored the plan to end the two-year-long marriage of their teenage children? I never got the answers to these questions.

Over the course of days and months, then years, my memory muddled, and I started to call my grandmother mother. My father, an aspiring young composer, became the center of my little universe. He would appear on weekends from the world of atonal music to borrow some cash from my grandparents and, along the way, check to make sure I did not listen to “pop” music like Chopin or Beethoven. He was busy with his artistic ventures and love life and impatiently awaited the day when I would be old enough to comprehend the big philosophical ideas that interested him. I did my very best to meet his expectations: I committed to loving Schoenberg and Warhol so that I would be deserving of his praise.

Busy impressing my father with yet another original thought so that he would not abandon me, and preoccupied with behaving well so that my grandparents would love me, I gradually forgot my mother. When I was nine, though, my classmate Marina asked me how the hell my father and I had ended up with the same mother. Marina was voicing the curiosity of ten other peers of mine who stood behind her, their eyes drilling into me. I honestly had no clue.

The question infested my mind. I began to wonder if what I considered to be pieces of an elusive dream were actually prints of some forbidden and forgotten reality. In one, a grey-eyed woman wrapped a towel around me after a bath; from the inner corners of my eyes, she cleaned what she said was the poo of a little mouse. In another, the clear drops of the piano music she was playing lured me to the other end of a different apartment than the one I lived in now. Was that forbidden Chopin? On my journey through the apartment, that younger me stopped by the living room, where an older woman—my other grandmother, I later realized—was sewing green-flowered underwear for my doll Nina.

I launched an investigation. First, I opened a drawer filled with obsolete toys and looked under Nina’s skirt. She was still wearing that underwear. Then, I excavated a photo album from under a tower of old Science and Life magazines on the bottom shelf of a wooden bookcase. I had noticed that album before and thought it suspicious, since the other albums were proudly showcased for guests. I cautiously turned the cardboard pages.

Among the glossy cards crammed with smiling gray faces, two drew me like a magnet. One was a passport-size picture of a teenage girl with a seductive look on her face. Dark hair framed high cheekbones. In the other, the same girl in a short 60s-era wedding dress was holding hands with my 19-year-old father. She was pregnant. My heart pulsated in my throat as I prepared to interrogate my grandmother-mother. I wouldn’t dare ask my father about such worldly, lay things.

My grandmother wiped the tears crossing the furrows of her face and explained that Svetlana, a young pianist, simply was not the right mother for me. She had not breastfed me long enough. At times, she would leave me with other people and go partying. She read the Bible — a sin in Soviet times. She did not like to wash my clothes, and she would lose patience and yell at me when she was cutting my hair because I would not sit still.

Besides, my grandmother had always wanted a daughter. Her own baby daughter had died in her arms between Aldan and Never on my grandparents’ long return to Moscow from visiting family in Siberia. Exhaust fumes permeated the covered truck. In her red velvet coat trimmed with white fur, the baby became clay pale. The parents banged on the glass of the cabin, but the driver refused to stop. He had people on board illegally and did not want to take the risk. “When we arrived to Never,” my grandmother sighed, “In ihren Armen das Kind war tot.”

To the nine-year-old me, my grandma’s reasoning felt logical. Don’t cry, mama. Thank you for saving me. Thank you for making me into your daughter.

I had to be grateful—snatching me from my evil mother had also been a big sacrifice for my grandparents, who were already leading busy lives. My grandfather worked on creating lethal weapons for the Soviet government, and my grandmother taught metallurgy at a university. They loved my father and were proud of him, even though they were a bit confused about what he called “music.” After his concerts, to which they invited their friends, they would shrug their shoulders, their smiles tinted with an apology for the cacophony, receiving with embarrassment their friends’ dutiful compliments. And yet, when they had no time for me, they would rather leave me in nurseries and summer boarding kindergartens than distract my father from composing, from his mission of translating the music of the spheres for the mortals to hear. In the nurseries and kindergartens, strangers pulled my hair as they combed it. There, people with faces I did not recognize pushed a spoon into my mouth while I was already choking on too much food. There, caretakers didn’t let me pee at night and punished me for wetting the bed. There, there. It was all for the better: my mother was young and revolting. She wanted to be free, and was, therefore, not ready for motherhood.

Later in my life, when people felt sorry for my motherlessness, I shrugged. Mothers were transient. Every time my father introduced me to a new woman he’d met, I’d prepare myself to be a possible child for her: Patricia from Chile, Katya from an amusement park, Alla from the theater, Natasha from Kazakhstan, Lena from the Conservatory, and others. Each seemed to want to be my mother for a while, and I did not mind being their daughter, but then one would be replaced by another and never return. I did not mind having a mother, but really, as I grew up, being motherless did not really hurt me anymore. It was as if my mother’s name was no more than words written on a piece of paper among the names of all the other women who could have become my mothers. The paper was made into a little airplane and carried away by the wind to lands beyond my reach.

***

Thoughts about my first mother began to sneak back into my head when I had my own baby. Singing lullabies to my daughter, I imagined how my mother had sung to me. As I rocked my screaming child for two hours, my arms becoming numb and disobedient as if made of cotton, I deemed it unfair to hold Svetlana’s impatience against her. In my exhaustion, I thought about that teenage girl who had just had a baby, and who had wanted to drop her burden and go party. Who wouldn’t?

I considered looking for her. Maybe, I could search through an old address book in my grandparents’ apartment for her number. I hesitated. What would I say? “Hello, I am your daughter. I am just checking on you after thirty years.” What if she had erased me from her memory? Would she want to talk with me? Was she even alive anymore?

Eventually, I had good reason to find out. My father’s fourth wife, unlike the many other women in his life, was serious in her intentions to become my mother. Though I was now an adult, and a mother in my own right, she decided to adopt me because she didn’t have children of her own. After her own miscarriage, making me her official child seemed like a solution. She thought, perhaps, obtaining adoption papers would tie the three of us together as a real family. I just needed notary-verified consent from my biological mother. What would be wrong with asking this of her? Growing up in a family that had cynically separated a mother from her child, and observing a succession of women who might have become my mothers and never did, I’d learned that mothers came and mothers went.

And there was yet another reason: since having my own baby, I had been growing curious about my birth mother. I was wondering if I would feel any connection if I saw her. I was even wondering if she was real. So, going to a notary public seemed like a good reason to meet Svetlana. Would her consent mean anything? Wouldn’t it just be dotting the i’s?

I went to my grandparents’ apartment when no one was there. In a shiny-from-use telephone book, with page edges reminiscent of dead moth wings, I found her name and number. I clenched the slippery phone receiver and listened to the rhythms created by the beeps layered over the pounding of my heart. Thirty years after I had desperately called her on my toy phone, I dreaded her answer. I almost hung up when a voice greeted me, thick with rust and residue. Yet I knew that voice. She was real. I said my name. Black silence swelled in the space between us. Then she punctured it, saying casually that she was glad to hear from me, and we made small talk about how we were both fine. After that, I explained why I was calling. She did not question anything. She did not protest. Easily and immediately, she agreed to meet me. She must have seen it as an opportunity to finally see me even if it was to officially sever our connection. We decided to meet at 12 p.m. the following day to go to a notary public. I suggested: “Let’s see if we can still recognize each other’s faces.” Svetlana paused and then said, “Well, just in case, I will be holding a plastic bag with a kangaroo on it.”

I entered the glass doors of the metro station and lined up with the people who waited near the wall. None of the women coming up the escalator looked at me with the uncertainty and persistence you would expect from a mother looking for the child she had not seen in 30 years. I kept glancing at the clock. 12:09—am I waiting in the right place? 12:16—some people are less punctual than others. 12:23—could she be scared to see me? 12:28—we must have failed to recognize each other. 12:32—another time, perhaps. Then the periphery of my eye caught a kangaroo on a plastic bag.

I turned and looked at the face of the lady standing next to me. A hot wave of disbelief jolted through me: the swollen face of a drunkard, roughly cut, greasy gray hair, a stooped figure that had lost its shape, a toothless smile. “Is that you?” she said. “We have been standing here all this time side by side!” An awkward hug.

On our way to the notary office, we fast-sketched the dotted lines of our lives. It would only take us twenty minutes to our destination, and there my mother would sign the document in which she would agree that she is not my mother after the many years of not being one. Ten minutes for each of our lives. Both of us must have felt it was futile to try to cram our combined sixty years of separation into that time. We hurriedly drew the outlines of the “main events” that we thought defined us, the carcasses of our lives. Svetlana told me she lived with her mother. She was working on and off at a newspaper for young parents. She proofread articles and letters selected for publication—a good eye for finding mistakes. No, unfortunately, the career of a pianist did not happen. There were reasons, she said, looking away, her lips pressed together into a thin, colorless line.

I told her about my teaching job, my husband, and her granddaughter. She was asking me about my future adoptive mother when we entered the dark notary office. “Oh, she is French! You will become half French, won’t you?” she asked. “Will I?” I wondered. We sat on a tired bench with several other people waiting in line, papers and folders in their hands. We were not in a hurry. She told me about my other grandparents. Her father, a military historian, had died two years before. Her mother still liked to sew. I asked her if she wanted to meet her granddaughter and she said we should make a plan. Then we were summoned “Next!” and entered a room with a peeling-off ceiling and a faded picture of a deer drinking from a brook in a chipped bronze-painted frame. The woman at the desk gravely asked us to present our passports. Then she read the document I placed in front of her on the table and glanced over her glasses at Svetlana with contempt. The notary slid the paper over to her. There were blanks where my name and my new mother’s name were to be inserted. Svetlana read aloud: “I refuse my parental rights and have no objectons for [you] to be adopted by…”. She cut out. “There is a typo in the word ‘objections,’” she sighed and signed the paper.

I called Svetlana about two weeks later, but my newly rediscovered grandmother picked up the phone. She said that she was happy to hear from me, and that Svetlana had told her what she knew about my life. Then I heard her sobbing. Right after our trip to the notary, Svetlana had begun drinking again, after a year of sobriety, and then she had left. My grandmother did not know where my mother was living. No, she did not have any other phone number or address. I called several times, but my grandmother did not have any news about Svetlana, who had shown up once only to ask for money. My grandmother sounded as if she was too tired to even want to know where her daughter was.

How could I have thought that Svetlana had ever really consented to our separation? That signature of hers tore us apart forever and tore her away from the flimsy world she was holding onto. For me, though, it had simply been a matter of obtaining yet another mother, as if I were an Olympic flame passed from one woman ripped of her motherhood to the next. I felt damaged. Could my own motherhood redeem me? For my daughter, I wanted to be what Svetlana had wanted to be for me but never could.

I stopped calling my other grandmother. I imagined my mother lying on the ground in layers of smelly rags, stoned, wet from piss, a kangaroo on a plastic bag keeping her company. I imagined how people pinched their noses and rolled their eyes as they squeamishly stepped over her. For many years afterwards, I kept looking at the faces of homeless women, at their hair, their eyes, their cheekbones. Any of them could have been my mother. All of them were.

An immigrant from St. Petersburg, Russia, and now a New Yorker, Polina Belimova teaches academic English to immigrants and first-year composition to the students of the City University of New York. “Another Mother” is her debut with The Common.

Drawing by the author.