With V. PENELOPE PELIZZON

Your name: V. Penelope Pelizzon

Current city or town: Willimantic, Connecticut

How long have you lived here: 13 years.

Three words to describe the climate: Southern New England. That is, winter lasts only five-and-a-half rather than six months.

Best time of year to visit? September and October are the safest bet for “good” weather. That said, if you’re someone who likes stomping around in the slushy woods seeing the first redness come into the trees, March can be pretty exciting. There’s a reason Thoreau tracked not only seasons but months just north of here; it’s a climate of extremes with all the sensual variety they produce.

1) The most striking physical features of this city/town are. . .

Willimantic is an urban-rural place in transition. It’s an old mill town within a few minutes’ drive of several big forests and land trusts. Great rivers of money once flowed in via thread manufacturing, but the mills closed in 1985. Now the downtown has some of the usual strip mall chains, as well as glorious but often empty nineteenth-century commercial buildings. Victorian houses in various stages of repair abound. There are serious attempts at revitalization: an organic food co-op; several quite good restaurants; a microbrewery; a rails-to-trails bike path linking downtown to the East Coast Greenway, a developing 2900-mile trail system running from Maine to Florida. It’s ethnically diverse: 18,000 residents identify as 8% African American, 40% Hispanic, and 50% White. Wildlife lives with us: this year a moose was spotted one town over; a couple of summers ago a black bear wandered up Main Street.

2) The stereotype of the people who live here and what this stereotype misses. . .

Willimantic is often stereotyped as “dangerous” because of the heroin trade documented in a Hartford Courant article in 2002. It’s home to a concentration of social service agencies, so there’s a transient population and people in various stages of recovery. But probably the “danger” image is as much a race projection; this is where brown people live, and Spanish is heard. It’s also a more urban locus in an otherwise rural area, so it feels “different.” Out walking the dog on a one-mile loop, I might encounter a panhandler, five old-school hippies petitioning outside the organic co-op for more green energy, two gay men with their daughter, a Marxist professor/colleague, skateboarders from Eastern Connecticut State University, the local lady who runs the kennel, a neighbor from Puerto Rico, and another neighbor who has Ben Carson promotional material on his lawn. Not long ago I heard Iraqi Arabic being spoken behind me in line at the Dollar Store.

3) Historical context in broad strokes and the moments in which you feel this history. . .

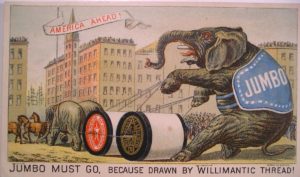

Entering town on the bridge over the Willimantic River, you see giant sculptures of frogs on thread spools. These commemorate two things. First is Willimantic’s heyday, when it was home of the American Thread Company, the world’s largest producer of cotton thread. The company closed in 1985, but for a century attracted immigrants from around the world. The frogs are a local icon from the 1754 “Battle of the Frogs,” when colonists mistook the croaking of bullfrogs for the war cries of a raiding native party. Artist Leo Jensen cast the four bronze frog sculptures; they weigh about a ton apiece, and viewers often note that they have extremely sexy legs for amphibians. Soon after you cross the bridge, you pass the building that for many years housed progressive Curbstone Press. You’ll also pass Poet’s Corner at the park named for Puerto Rican writer Julia de Burgos.

4) Common jobs and industries and the effect on the town/city’s personality. . .

It’s impossible to overstate the impact of the American Thread Company. The architecture of the town is what you might call American Industrialist Integrated Vernacular: around the riverside and near the mills sit older, poorer multifamily buildings. Up the hill that rises away from the mills you find increasingly-ornate Victorian houses. In a rectangle spreading from this center are later twentieth-century houses, with split-level ranches built between the 1960s–1980s, a dominant design. The town’s multi-generational immigrant populations—many arrived to work in the mills—mean that a Polish breakfast place sits across the street from a panaderia, a taqueria, and a Jamaican restaurant (called—yes—“Jamaican Me Crazy”). Eastern Connecticut State University’s presence creates a booming real-estate market for (overpriced) student apartments. The old stone mill buildings have been rehabbed in the past decade into offices and apartments; one houses an art space.

5) Local/regional vocabulary or food?

This is the land of fish. It’s a cliché to eat a lobster roll, but what a delicious cliché! It should be hot—just fresh hot lobster meat soaked in real butter on a cheap white hotdog roll. (Why does the bread have to be so crummy? I don’t know, but it does.) Steamer clams are a specialty, too; you have to learn how to peel the foreskin-like neck tissue off and dip them in hot salt water to get the sand off, before you dip them in butter. In February you see a lot of maple-tree tapping going on in the surrounding towns if not Willimantic per se. Bigger farms hook yards of plastic tubing between the trees; I swear you can hear a low, rushing, sucking sound as the sap pushes from the tree through the tubing to the collection vats. By April, someone has often gathered ramps and fiddleheads you can buy at the Willimantic Food Co-op.

V. Penelope Pelizzon’s most recent book of poems is Whose Flesh is Flame, Whose Bone is Time.

Photo 1: courtesy of Digital Commonwealth

Photo 2: by author