SCOTT GEIGER interviews MATTEO PERICOLI

To go from inspiration to the completion of a work of art or literature or architecture is a voyage in the dark. Artists smuggle intuitions from a place beyond words into achievements the public can regard and appreciate or not. This voyage fascinates the Italian architect Matteo Pericoli, author of the new book Windows on the World, which collects 50 of his drawings published over recent years by The Paris Review. Strong, solid lines render rooms around the world, rooms where every day the likes of Orhan Pamuk, Teju Cole, Francisco Goldman, and others sit down to do their writing. In Pericoli’s drawings, the architectural feature of the window frames a writer’s consciousness.

I met Pericoli one morning in November at New York’s Neue Galerie. We talked over an early coffee before heading upstairs to look at the museum’s special exhibition of Egon Schiele’s portraiture.

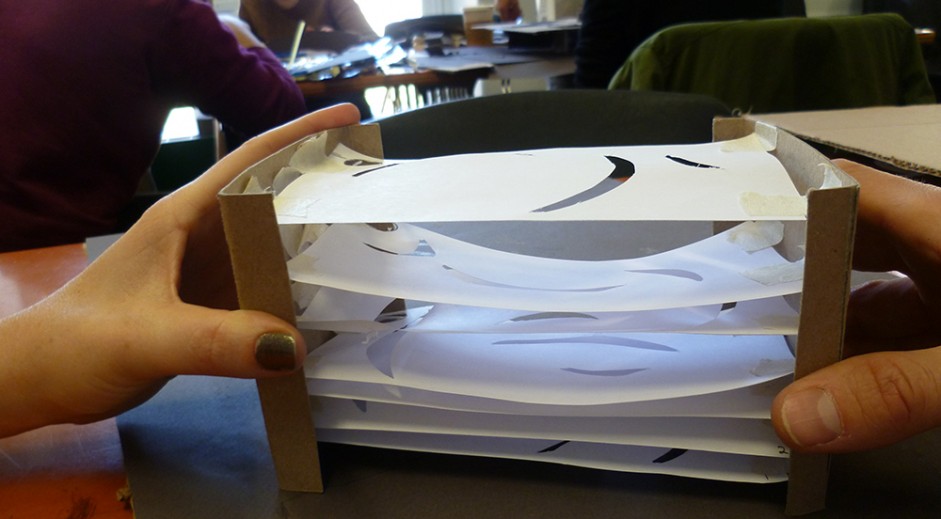

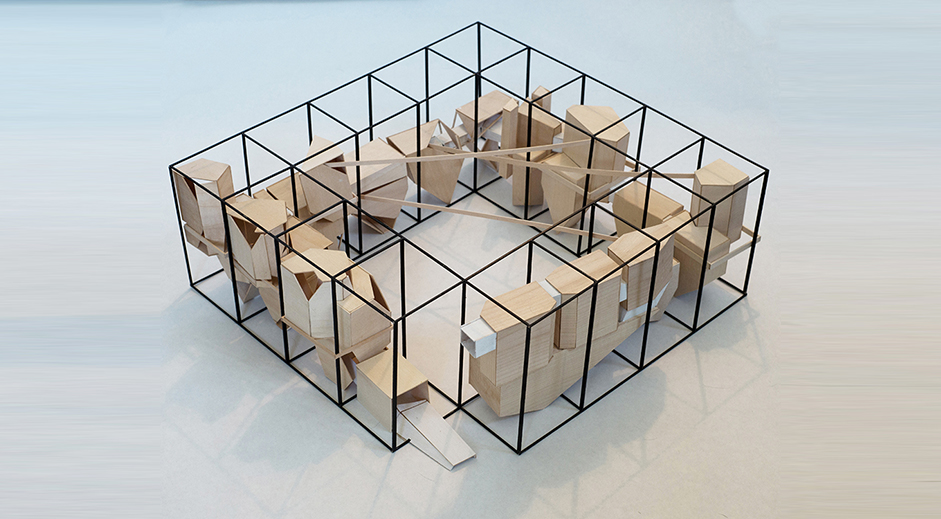

I wrote last year about Pericoli’s Laboratory for Literary Architecture, his graduate writing course at Columbia University where MFA students worked with architects to produce physical models of literary works. After our visit at Neue Gallerie, we sat in the sun outside Central Park’s Delacorte Theater discussing the Laboratory, writing as a design process, and reading as a spatial adventure.

Scott Geiger (SG): What can you tell me about your agenda for the Laboratory of Literary Architecture? What are the models students are making in the Laboratory exactly?

Matteo Pericoli (MP): The spirit has always been one of experimentation. A gamut of ideas springs out of a book, a physically nonexistent thing.

One model translates how, hypothetically, the designer, the writer, set out to build the novel before the words went all around and made it real. Say I have a space filled with action and relationships, the void of someone dying or disappearing, then a reunion of something that is the same place but clearly with some kind of loss in between. This I think is a literary-spatial idea that could have come in a writer’s mind before the words were ever on the page. That, I think, is a successful project, in the experience of the Laboratory, because it expresses the essence of the novel and why it works and doesn’t fall. It has an architectural structure that could be built. You, as a one-day visitor don’t recognize the novel but go through and experience a space, seeing the thoughtfulness of a concatenation of things that clad nothingness, which is space.

Another model expresses how the reader lived the reading of the novel—as in, This is how I felt the novel. I felt I was constantly brought to the edge of something that was going to happen and I was going faster in the reading but never getting to it. Maybe that was a design or maybe it was my reading. But that’s another very appropriate model. There is not one solution that works, there’s only how I experience architecture. When you go into a 20-story building in New York, you think, Look at this cute building. But when you go into a 20-story building in Turin, you think,Whoa, this is huge. When we think of a work of architecture we always try to put it in context. Is it a park? Is it a building? If it’s a building, what are the other buildings around it? When you read a novel, likewise, you read it in the context of your age, your mind, your culture—even though there is an essence to the work.

A final model is that of the life of the protagonist. He goes through misery and he has always shifted from one place to the other, never realizing his life is like a flag in the wind. So I’m replicating the protagonist’s experiences, which is not impossible as a way of imagining a writer-designer who says I want to come up with a book’s literary architecture about a person who goes through these things.

So I would say these are the three areas of focus in the Laboratory, broadly: the very subjective, the subjective in terms of a protagonist, and that pseudo-objective replica of authorial design.

We always are very careful not to dismiss anything for any preconceived idea, but it’s important we can always tell when something is going in the wrong direction. One problem is when you read To the Lighthouse and you think, literally, lighthouse. Or you think simplistic things, like good is up,bad is down. Architecturally, as the Guggenheim Museum teaches us, down is actually good. Things are not always a then b then c,becausesometimesa followsb. You thinkthis person is good because they have achieved something, yet that person is bad because they killed somebody. That is not a story. You wouldn’t explain either a story or architecture in this way. And I think this is part of the magic of the Laboratory. And, you know, two different people can create models for the same novel, and they can get totally different projects.

SG: The process of the Laboratory opens up so many values released by the encounter with the work. You can get a physical document of a reader’s response or the replica of the artist’s intent.

MP: Reader-viewer, or the personal experience of architecture, is probably the best way to show this overlap of literature and architecture. Not intersection, overlap. You know a book, if you’ve entered into it on page one and exited on the last page. At Columbia, Fiona Maazel has a course about the devices you, the writer, can apply to make the reader not stop reading. That’s space! Architects present you with sequences of spaces, inviting you to immerse yourself, such that you learn but do not discover everything right away. You don’t want to move too fast or too slow.

SG: Do you think an exposure to literary space makes them better storytellers? Perhaps architects need to be better storytellers.

MP: I agree with that. When the tower for Ground Zero was announced, with its height of 1,776-feet height, that’s exactly what does not work. That’s not a narrative, that’s the most literal thing. The most successful moments in architecture are when the experience of space is truly arranged or composed or designed to be a piece of narrative or storytelling. The need of the visitor to a building is the same as that of the reader to a story. I get into an apartment or a room, and if the plan or the lighting is bad, it’s as if the writing were bad. Reading things that have nothing to do with architecture and understanding them, is a way of preserving your instincts about design—a vital curiosity enhances your ignorance.

SG: “Enhanced ignorance.” I love that as a premise, and it’s true. When you’re in a really well done space, your mind opens up.

MP: Right. I don’t want to know anything for certain. The Italian architect Michelucci, after 60 years of life, 30 years of practice, realized it’s about space. It’s about what’s not there, and it took him 30 years of forgetting what he’d been taught in order to realize that. Often I wonder if it’s not the same with writers. How do you get from the instinct of the story, which has zero words as of yet, to the completed work? It’s your ability to clad it with the words of your language, your culture, your century. Because 100 years into the future or 200 years ago, that same pure idea would not have been expressed in the same way.

SG: It’s almost as if a work is something atemporal. Then the artist arrives at the moment in time when the work can be made.

MP: Atemporal and wordless. We have this problem of language. I often want to think without words, but my brain doesn’t allow it. When we are in the Laboratory, we are forced to do so.

SG: How can writers hone their sense for space? Do they travel for research? Experience cities? Parks?

MP: Well, you can sit right here and still cultivate your curiosity, I think. Traveling with a true open mind is very hard. It all depends on how you set out to do that; whether we’re talking about architecture or literature, are you ready to change your vision?

Scott Geiger is the Architecture Editor for The Common.