Eastern Shore, Maryland

My late husband was a man who invented facts. He was Danish by birth, and at a dinner party he mentioned that aardvark was Danish for hard work. “Copenhagen households keep them to clean the floors,” he said. Our otherwise intelligent friends, who hadn’t been to Denmark, believed him.

He told overnight guests about the time I was flashed at a train station. He claimed that when a police officer asked for a description, I held my hands a foot apart and said, It was about this big. Our friends, who like us were in their mid-fifties, believed that, too. I was mortified. I protested, “That’s not true. All I noticed was the flasher’s trench coat.” After our guests left he asked, “Why would you ruin a perfectly good story?”

In revenge, I decided to prove I was equal to his game. On a steaming Friday afternoon, he and I set out from our home in Washington, D.C., for a weekend in Chincoteague. He was driving and listening to music. I had three hours to plan.

All the way to Annapolis I dreamed up gossip from my politically-connected hairdresser, gossip I hoped he would believe, gossip he would pass on to out-of-town relatives as a first-hand account of what happens behind the scenes in Washington. But by the time we’d reached Kent Island, I was stumped. What imaginary scandal could top Congressman Wilbur Mills’s dive into the Tidal Basin to avoid being seen with the stripper Fanne Foxe? What could outshine Congressman John Jenrette having sex with his wife on the Capitol steps?

In Easton we passed H & G, a family-owned restaurant with perfect home fries and a toy train that circled the map of Maryland on the ceiling. H & G was on our family roster of quirky Eastern shore landmarks along with the fresh-muskrat-meat stand in Fruitland, the Eat Here Before We Both Starve Diner, the giant toast that popped up from a Salisbury billboard, the strip mall where we’d seen an elephant tied to a stake, the One-Way sign on Cemetery Street in Cambridge, which John Barth memorialized in a novel, and Blanche’s Funeral Parlor, which my husband had noticed on a back road when we were driving to Chincoteague in separate cars.

Shortly after Easton, we passed the tie-up of gawkers near the Tuckahoe Tractor Pull, an invention for grown men who liked playing tug-of-war. My landmark needed to be as good at that tractor pull. It had to make him slow down the car.

No, it needed to be better, like the neon sign in front of Blanche’s that blinked Home of the Cool Cadaver—a you-just-missed-it site—so he’d turn the car around.

Near Vienna I was juggling ideas when traffic came to a standstill. We had just passed the last turn-off for an alternate route. There was no place for a U-turn. We were trapped by cars and endless cornfield. He turned off the ignition.

We lowered the windows. People tossed frisbees on the median strip. A woman in a bright green leotard did wheelies on her bicycle on the now-empty, northbound side of Route 50. A guy in an eighteen-wheeler with a CB radio shouted that the problem was the open drawbridge across the Nanticoke. Guess who wanted to announce that the drawbridge had opened for the Sequoia, the Presidential Yacht, and that he had inside information that the President would be on it. I held him back. He could be so believable that he might cause a stampede to the river.

By then our jeans and t-shirts stuck to the seats. His mood fizzled him flat, like a tire that had lost its air and was hugging the road. “We could be stuck here for hours. We should have eaten pizza in Cambridge,” he complained.

I reminded him that the week before we’d waited so long for pizza that we’d seriously contemplated using the pay phone in the restaurant lobby to get faster delivery from a competitor. “We’d still be waiting,” I said.

He pointed to the glove compartment. “What’s in there?”

Badly folded road maps, plastic spoons in cellophane wrappers, a packet of towelettes, and a pencil stub.

Could I talk him into eating that pencil? I imagined an article in Office Worker News on the dietary value of trace minerals, which quoted a study—New England Journal of Medicine, well-controlled, I would say—on the surprising nutritional benefits of gnawing on pencils. But why risk letting a perfectly good husband choke to death just for a moment of revenge? “Nothing you can eat,” I said.

“What restaurants are in downtown Salisbury?” he asked. Frustration oozed from his pores.

I tried to remember. There were none on Camden Avenue, which we took to avoid traffic lights, a right turn immediately after the Perdue chicken processing plant. As I recalled, the plant was squat, cement block gray, surrounded by chain-link fence, and—eureka—“We haven’t tried the Perdue employee cafeteria,” I said.

The excitement pounding in my ears was so loud that I hardly heard him say, “Perdue has a cafeteria?”

“I forgot to tell you when it opened to the public last month. It’s highly recommended.” I was ready to describe gleaming white walls, stainless-steel counters, and colorful trays with Frank Perdue’s picture on every one.

I didn’t have to. He said, “The chicken will be really good. Perdue wants its employees to have confidence in its product.”

How typical. Although I hadn’t yet heard the word mansplaining, I realized that his desire to show he knew more than I did was turning him into putty in my hands. “Excellent point,” I said, adding that I’d heard they fried up the pope’s nose with a really good crunch.

“The pope’s nose?”

When had we started moving? We were crossing the Nanticoke. “You know, the delta-shaped tail. My mother stockpiled them until she had enough to crisp in chicken fat. My sisters used to fight over them,” I said.

“Must be like chitterlings,” he said as we passed the house with the topiary sofa and chair in a weedy front yard, another landmark on our list.

“Better. More like the crackling on your pork roasts.”

“Why not?” he said. He made crackling well. We passed the sign to Dames Quarter without his usual jokes. We sped past Pop Pop’s fruit and vegetable stand. If he hadn’t been so focused on chicken, we would have stopped for peaches. Now I was hungry.

I fantasized about food. “The cafeteria’s cold chicken consommé would be refreshing on such a hot night, and they serve chicken cutlets, fried chicken, roast chicken, chicken Caesar salad, and capon stew,” I said.

“I wonder how they cook wings.”

In flights of fancy, of course. Why didn’t he realize that? “Oh! I should have told you,” I said, “on Fridays they dredge wings in crab spice, sauté them with a touch of hot chili oil, and give you cocktail sauce for dipping.”

“Ah,” he said—as if my Friday night special were reasonable.

I moved down my menu to chicken kidney pie, chicken scrapple with grits, and gizzard salad. When would he catch on?

As we zipped along, he said, “I’ll have that pope’s nose for my appetizer and a plate of chicken legs with coleslaw. They do serve chicken legs, right?”

Pulled chicken legs, dear husband.

We passed Hebron and were near the turnoff to Bivalve. Maybe a platter of boiled chicken heads would have broken his trust in my cafeteria, but it was only years later, when a friend sent photos of his lunch in Shanghai, that I learned that chicken heads were food, served with cilantro.

We were approaching Camden Avenue. “The parking lot’s around back,” he said. “That’s where the gate must be.”

A gate?

He moved into the righthand lane for the turn. Would there be armed guards protecting Frank Perdue’s trade secrets? “It’s late. We should find the takeout window and eat while we drive,” I said. And then—I have no idea where the thought came from—I spurted out, “Chicken feather sandwiches are the house specialty.”

He slowed the car and flicked the right turn signal. People who make up facts are so gullible, I thought. Just as it occurred to me that he must have convinced himself of a culinary process, using a blow torch perhaps, that transformed chicken feathers into a mouth-watering spread, he pressed the gas pedal. With the right turn signal still clicking, we shot straight ahead. “It takes too long to lick feathers off your teeth,” he said.

Touché!

That weekend in Chincoteague and later back in Washington, he urged friends to try the Perdue Cafeteria. “Don’t forget to look for the Pope’s Nose on a Stick and the yellow bags of candied chicken lips beside the cash register,” he said.

“Chicken lips?” I asked when we were alone.

“Chickens don’t have lips,” he explained. His expression said you dummy.

It was many years later, long after his death, that I received the email with the photograph of that Shanghai lunch. When I saw the faces on the chicken heads my friend was about to eat, I realized that, sans beaks, chickens do have lips, little pouty, kissy ones. You can find images on the Internet. If only I had known that while he was alive.

I wish I could tell him that although the H & G and the pop-up toast are long gone and the Nanticoke drawbridge has been replaced, the Perdue cafeteria remains high on our family roster of Eastern Shore landmarks, right up there with Blanche’s Funeral Parlor and its neon sign. He would be glad to know our game lives on. Blanche’s would have been perfect for his funeral. I wish I could tell him how hard I tried to find it.

Cynthia Graae lives in New York City and Hiram, Maine. She writes short fiction and nonfiction. Her late husband, who appears in “Fowl Play,” also appears in her stories about: falling in love (The Bridge: Journal of the Danish American Society), his temper (Griffel), being robbed at gunpoint (Humans in the Wild: a Swallow Press anthology about gun violence), going to a furniture store with their daughter (10 x 10 Flash), and his success at explaining cloudless rain (Alternate Route).

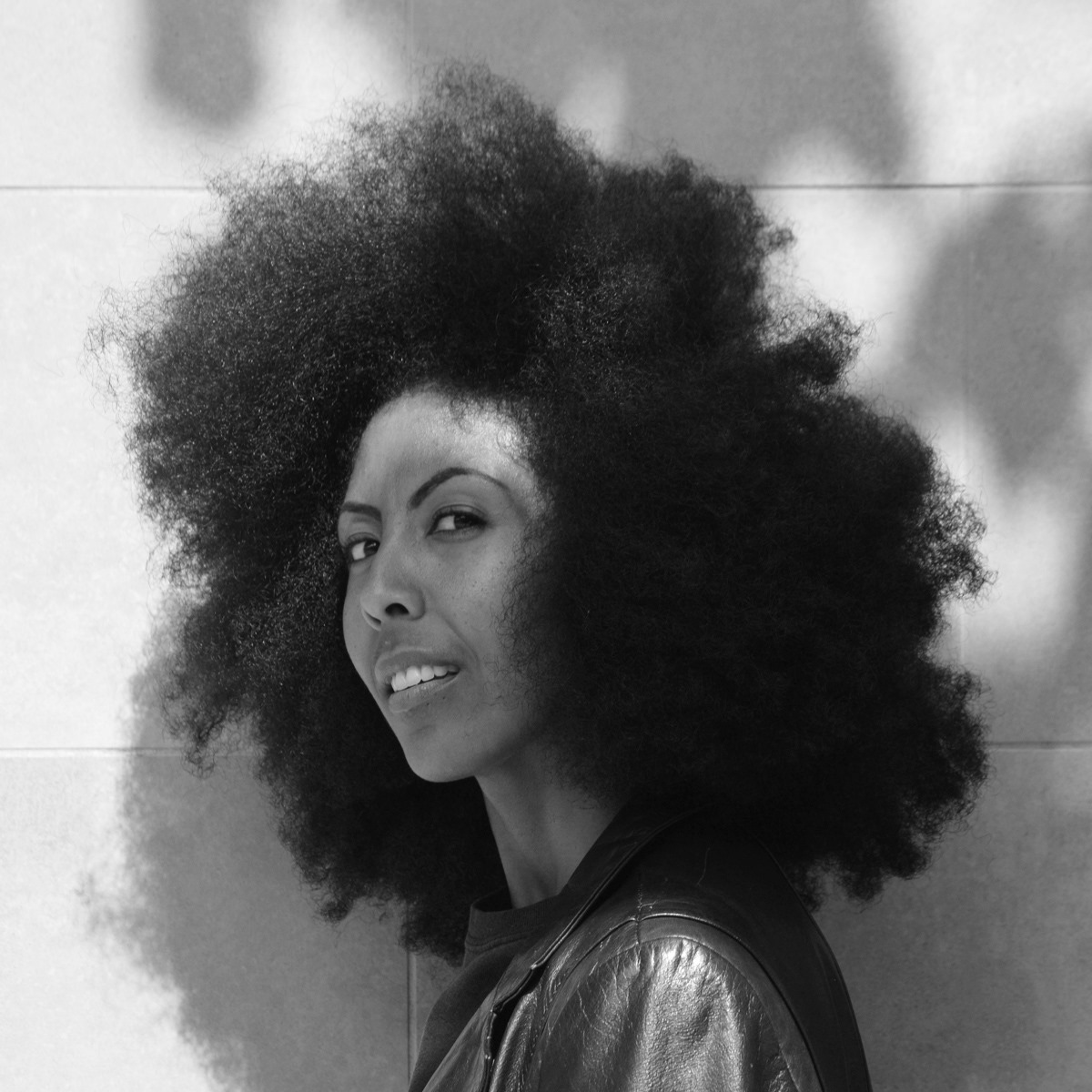

Featured photo by Pexels user Italo Melo.