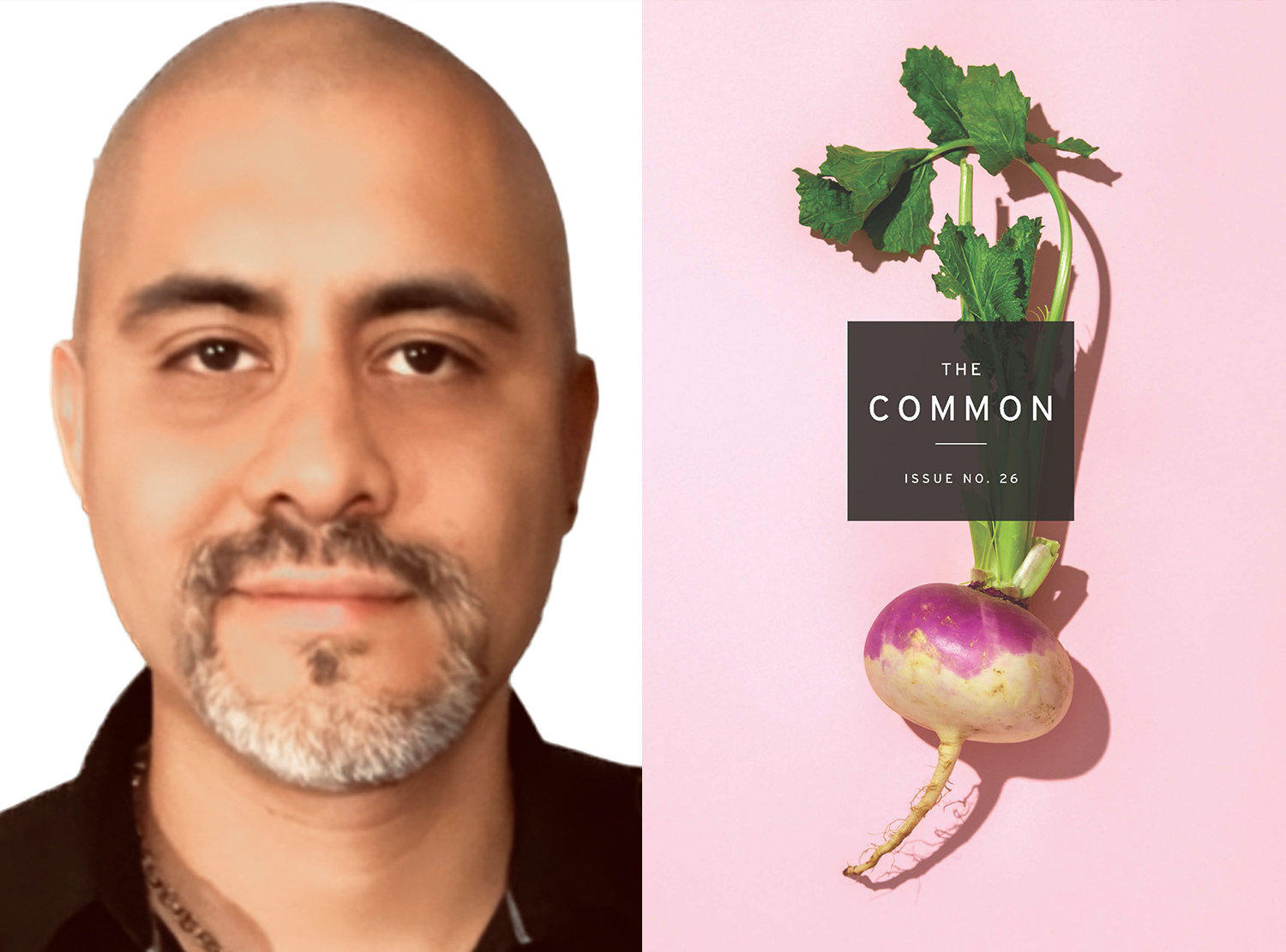

By LEI HU

A Good Girl

When she stepped outside and closed the door, the iron handle was so cold, it felt like it was burning. With the basket on her arm, Fu Rong slipped her hands into a pair of cotton mittens her mother had made. She knew she would warm up once she started walking. The stone lane in the village was slippery with ice; someone must have spilled water carrying it from the village well to their house. She slowed down and kept her pace steady, leaving the village behind her.