By SCOTT GEIGER

Last month I enjoyed following media coverage of an unusual writing workshop and design studio held at Columbia University. Italian architect and writer Matteo Pericoli originated his “Laboratory of Literary Architecture” course in Turin, and brought it to New York this spring as a joint course for students of the School of Writing and the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.

Part of Columbia’s Mellon Visiting Artists and Thinkers Program, the workshop coordinates collaboration between student writers and student architects toward a radical goal. Pericoli has charmingly presented his studio in The New York Times and in The Guardian this way: “I encourage the students to find—or, rather, extract—and then physically build the literary architecture of a text.”

I smiled, thinking about a post I wrote here last May, “Speculative Summer School,” in which I was just dreaming up themes for writing workshops structured like architecture studio courses. These classes might be for architects or writers, I thought; each would work within their own discipline, deploying their the own tools in parallel investigations. Pericoli’s workshop is both purer and conceptually more daring. His writers pair up with architects to produce a single project: a physical model that renders a well-known text into an architectural experience.

You can read more about the course from the Columbia University’s page for the School of the Arts. The SOA advertises that, “The students used basic materials: paper, pencil, cardboard, scissors, tape, and box cutters. There was no expectation of previous experience in design or model making. The goal was for each student to dig deeply into his/her text in order to reveal its architectural and structural essence, as he/she perceived it.”

“It is a process of reduction toward a wordless spatial structure,” Pericoli continues in his piece for The Guardian. “In architecture, once you remove the skin—the ‘language’ of walls, roofs and slabs—all that remains is sheer space. In writing, once you discard language itself, i.e. words, what’s left?”

I’d pay to read transcripts of conversations within the teams. Joss Lake (Columbia SOA Fiction) and Stephanie Jones (Columbia GSAPP M.Arch ’15) worked on Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald, and they describe their model in a design statement:

“The structure is a tall and narrow space, reflecting both the vast scope of the book as well as the intimacy of the reading experience. An uneven path is suspended along metal supports, and gradually rises and falls across the entire length of the structure. The path’s shape is dictated by the fragmented and surprising nature of the narrative, in which the novel leaps from subject to subject through unconventional avenues, such as the documentary playing in the narrator’s hotel room… The darkness of the tall and narrow space is broken by clusters of light bulbs. The constellations of lights are not comforting; they too are disconcerting … These light bulbs are the core of the novel, the details that Sebald, and his narrator, use to recover the past.”

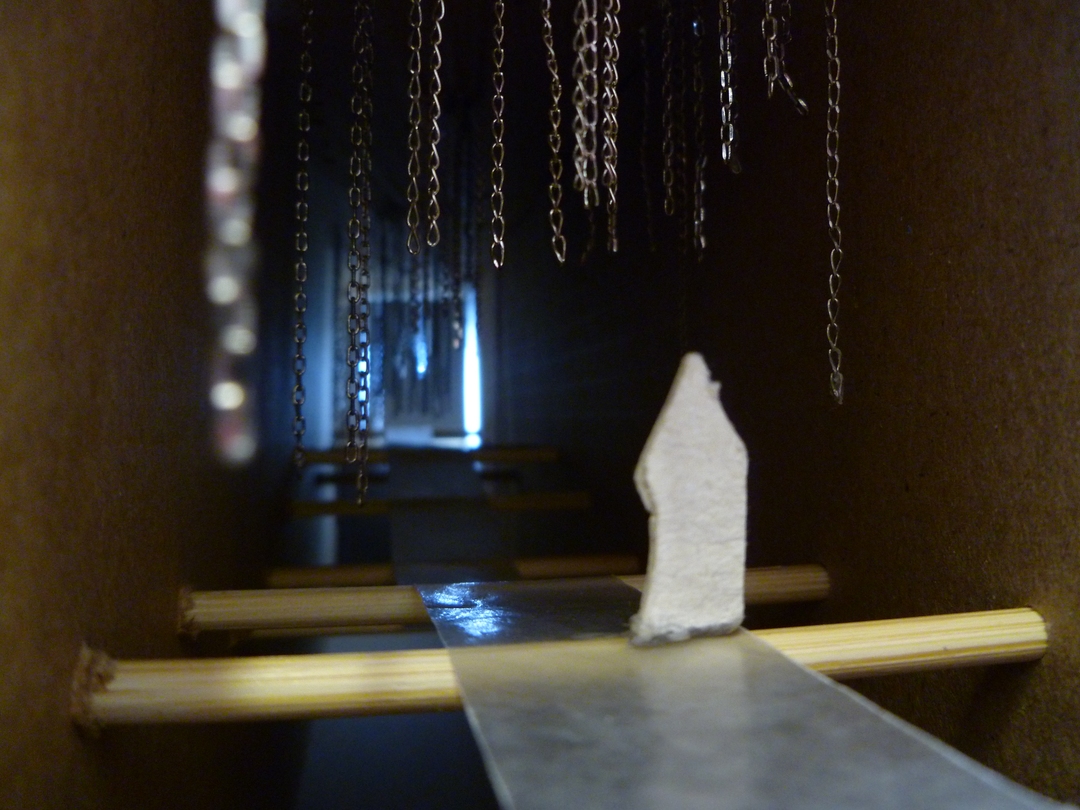

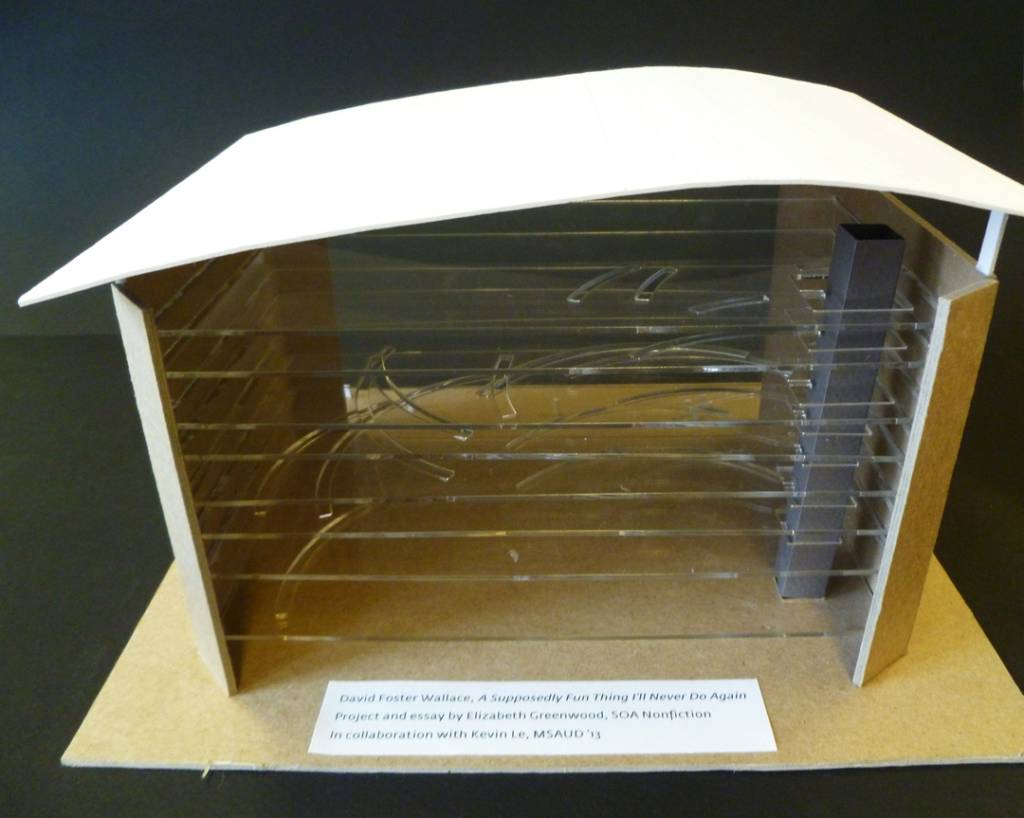

Matteo Pericoli’s stated agenda is “Literary, not literal.” Teams cannot design a text’s setting: for example, David Foster Wallace’s “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” cannot be modeled as a cruise ship. Elizabeth Greenwood (SOA Nonfiction) and Kevin Le (M. Arch ’13) instead produced “a rectangular structure with many floors” inspired by the structure of Wallace’s sentences. Of their project, they write:

“[We] designed a rectangular structure with many floors. Bolstered by concrete brackets, the end pieces represent the hard, inescapable fact of heavy things in the essay: the Harper’s assignment, the ship itself. But the floors inside these brackets are made of glass to represent the clarity and truth Wallace sees during his time at sea. On the outer edges are two parentheses turned away from one another (which might one day be openings for stairs) representing the thoughts and connections between seemingly unrelated things. These cuts into the plexi allow light to filter through between the floors, illuminating their invisible links and also tracing seemingly disparate themes and digressions. As the floors ascend, these parentheses edge closer to the upper right corner, where an elevator shaft penetrates through the structure. This burst of continuity between floors represents the author’s presence, and the author himself, who cannot be contained even within the clearest of glass, and who stubbornly refuses to be subdued even in the most ostensibly light of occasions, like a vacation on the high seas.”

If nothing else, Laboratory of Literary Architecture demonstrates that literary works are made meaningful through our experience of them, through the way we use them. Like buildings and public spaces and parks. All are enriched when we make the venture together with friends.

I am reminded of Edward Gauvin, who has been asking me to clarify an intuition I shared with him a couple years ago, while we were discussing his translations of French novelist and tale writer Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud. A prose fiction, I said, might be like a graphical-user interface (GUI) on a software application—the thin digital layer of user experience placed atop a larger, crazier operating system, something running on dark oceans of computer code. Like the part an ATM we see. Like a smart phone. As a translator, Gauvin has created Châteaureynaud anew for English readers. A good writer or translator is a good user experience designer, I said.

Experience is the axis on which the “Laboratory of Literary Architecture” spins. The Laboratory for Literary Architecture pushes students to compose through their model a fictional architectural experience. Donald Bartheleme’s “Concerning the Bodyguard” is “translated into skyscrapers.”Raymond Carver’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” is a pavilion inside a “sunken ellipse” with a “false wall.” Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse is a house set on a steep cliff.

I wonder how the writing and the designs of Pericoli’s students will evolve over the rest of their time at Columbia. In its coverage of the Laboratory, the premier social media platform for the architectural community Architizer suggests “perhaps architecture schools should reintroduce writing classes where possible, in order to teach architects how to think in narrative, in metaphor, and ultimately, to translate these concepts into imaginative spatial structures.”

I am in strong agreement about Architizer’s point indeed. But I also bet Pericoli’s writers have collected the windfall here. Now I wonder what they’ll make of it.[1]

Scott Geiger is the Architecture Editor for The Common.

[1] Long ago, before going after my MFA, I remember reading that Ben Marcus began drafting the first stories that would become The Age of Wire and String in a challenging seminar at Brown with Robert Coover called “Ancient Fictions.” This anecdote is one of the reasons why I went to graduate school.