ZINZI CLEMMONS interviews ELEANOR STANFORD

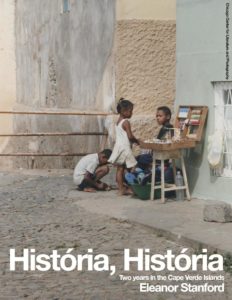

Eleanor Stanford is the author of the memoir História, História: Two Years in the Cape Verde Islands, and of a poetry collection, The Book of Sleep. Stanford’s essay “Geology Primer (Fogo, Cape Verde)” was published in Issue No. 06 of The Common. Fellow Philadelphian Zinzi Clemmons chatted with Stanford about poetic form, the importance of language, and ways to feel at home in the world.

Zinzi Clemmons (ZC): Where is home for you?

Eleanor Stanford (ES): Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania (just outside Philadelphia).

ZC: Where did you grow up?

ES: Outside D.C. My family moved to the Philadelphia suburbs when I was 12.

ZC: Are you able to feel at home wherever you are in the world, or do you find comfort in leaving, and returning home?

ES: I think writers always feel at least a little bit out of place wherever we are. (Or maybe that’s just me.) There is a quote by the poet Czeslaw Milosz that I thought about often when I was in Cape Verde: “Language is the only homeland.” I took (and continue to take) some sort of comfort in it.

ZC: Your essay in Issue No. 06 of The Common,“Geology Primer (Fogo, Cape Verde),” takes the form of a glossary of geologic terms. The glossary definitions are both factual and anecdotal. In a sense, your definitions actually resist definition. What element inspired this feature of the essay? How important is language to you?

ES: As a poet, form is of paramount importance to me, and often the spark of a piece (prose or verse) occurs in finding the form. For “Geology Primer,” the glossary allowed me to use some passages I had written a long time ago, but which hadn’t yet found a home, and I added many more to fill it in.

Language is extremely important to me (see the Milosz quote above). This is true in writing, of course, but took on new resonances as I thought about the languages of Cape Verde—Portuguese and Kriolu, a Portuguese-African creole. Learning Kriolu and immersing myself in it was one of the main ways I began to relate to Cape Verdean culture, and because it is so fundamental to understanding the place and its people, it suffuses much of my writing about my time there.

ZC: Your essay evolved from your stay in Fogo as a Peace Corps volunteer from 1998 to 2000. A Peace Corps Worldwide review says your book “captures the ambivalence of being there, the love/hate relationship on both sides, the desire for connection and the desperate need for solitude, the wish to fit in and the resistance to going over completely into the other culture…”. Does this describe your experience there as a volunteer? How did your professional role mediate your experience of the area?

ES: Yes. I tend to be a solitary person by nature, and Cape Verdean culture is very communal, so that was a challenge for me. It was also a struggle to live in a very traditional, machista society as an American woman.

I worked as a teacher at the high school, which allowed me to become a part of the community, to become friends with Cape Verdean teachers and get to know something about my students and their families.

ZC: Have you returned to Cape Verde since 2000? Have you thought about how it might be different returning a second time, under different circumstances?

ES: I haven’t been back. I have thought about it, and while part of me would love to return, and see the people who meant so much to me while I was there, and to be back in that striking, unusual landscape, circumstances have prevented me. (It’s quite expensive and difficult to travel there, more so since I have three kids.) I also know Cape Verde has changed in many ways—more development, cellphones, paved roads, violence in the capital—and in some ways is no longer the same place I lived fifteen years ago.

ZC: A few years after Cape Verde, you lived in Brazil with your family, and wrote about that time in a 2011 essay. How did that visit, undertaken for personal reasons, compare to your time in Cape Verde?

ES: In many ways it was quite different. I had my children with me, of course, which makes for a different experience than being young and single. My husband and I were also working at a fancy international school, not at all like the disadvantaged local school where we taught in Cape Verde. On the other hand, I did feel a similar warmth from the people I met in Brazil, and there are a number of similarities in the cultures, as developing nations and former Portuguese colonies.

ZC: Aside from essay writing, you’re also a widely published poet. Do specific journeys inspire your travel essays, or have you always been drawn to travel writing as a genre? How does the genre differ from poetry? Does it afford you more creative possibility, or less?

ES: My travel essays have been inspired by visiting a place, and feeling the need to explain that place and my experience of it in a sustained, literal way. The thrill of poetry for me is how it allows for a certain obliqueness, for different and unexpected ways of using language and getting at meaning. I suppose in some ways there is less (or different) creative possibility with nonfiction, as the writer is bound by what actually happened, and usually more subject to the conventions of syntax and narrative.

ZC: Which travel writers, if any, do you draw on for inspiration and guidance?

ES: I am most interested in writers for whom travel is not an end in itself, but a way to explore some other question or obsession—for example, Geoff Dyer, Alexandra Fuller, Olivia Laing.

ZC: Have you traveled much outside of Cape Verde and Brazil?

ES: Not really. I’ve taken short trips to Senegal, Venezuela, and France.

ZC: Are you planning another journey? Where in the world would you most like to visit next, and which place would you most like to write about?

ES: I am! I am a Fulbright fellow for 2014-2015, and will be back in Brazil, this time in the interior of the state of Bahia. My plan is to research rural midwifery there, for both a novel and nonfiction writing.

*

Eleanor Stanford’s “Geology Primer (Fogo, Cape Verde) “was published in Issue No.06 of The Common.

Zinzi Clemmons is a writer and editor living in Philadelphia.