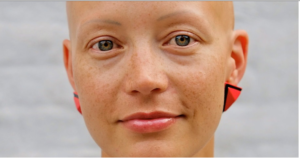

HILARY LEICHTER interviews HELEN PHILLIPS

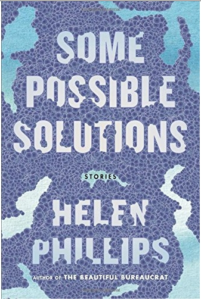

Helen Phillips was born and raised in Colorado. She is the author of four books, most recently the short story collection Some Possible Solutions. Her novel The Beautiful Bureaucrat was a New York Times Notable Book of 2015, and a finalist for the NYPL Young Lions Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her collection And Yet They Were Happy was named a notable collection by The Story Prize. Helen has received numerous awards, including a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award, the Italo Calvino Prize in Fabulist Fiction, The Iowa Review Nonfiction Award, the DIAGRAM Innovative Fiction Award, and a Ucross Foundation residency. She is an assistant professor at Brooklyn College.

This summer Hilary Leichter met with Phillips at Elk Cafe in Brooklyn, NY, where they discussed wordplay, weirdness, and confronting the void.

Hilary Leichter (HL): The world today seems to move ever closer to the realm of science fiction, the absurd, the surreal. I heard someone say recently that realism was the new fantasy. Do you feel like a realist writer, even though you often work in the fantastic?

Helen Phillips (HP): What you ask resonates with me because I do always feel like what I’m writing about is just a slightly different version of reality. It doesn’t feel like I’m doing something that dramatic. I see a smudge on the wall in my office and I think, “what if that’s a handprint?”

One of the stories in Some Possible Solutions, “The Beekeeper,” is about a world in which teenage girls and their objects are disappearing. I wrote that around the time the earliest articles were coming out about the bee population’s disappearance. To think that these bees—such a symbol of fertility and fecundity—are disappearing seemed so science-fictional to me. So I wrote a science fiction story about it. I don’t feel like I’m a realist writer, but I do feel like what I’m interested in is just one or two steps off of the familiar.

HL: Right. So you’re on the cusp of reality.

HP: Yes, on the cusp of reality. I think some writers veer far away from reality really well, really excitingly. I’m more interested in ambiguity. With “Contamination Generation,” the final story in Some Possible Solutions, some early readers asked me, “Wait, is this set in our world, or in a dystopian world?” And that’s exactly the question I want people to be asking when they read my work.

HL: So you described seeing the smudge on the wall and wondering, well, what if that’s a handprint? Do you normally start your stories or novels from some sort of image or tangible thing in the real world?

HP: I would say image is where I start. I was on a panel at a SLICE conference, and one writer said “I begin with plot,” another writer said “I begin with character,” and I said, “I begin with image.” It was so interesting to have three of us on that panel feeling like the first thing that comes to us is a very different component of the process.

Sometimes overheard dialogue in the street or on the subway can be generative. You overhear two lines of dialogue that out of context seem like they come from an alternate reality. At times I use those seeds of language, but mainly I begin with image. A bee vanishing out of thin air, or a woman going to the grocery store and seeing a woman who looks identical to her down the aisle from her, these weird little moments.

This is an odd way to write a story, because an image alone doesn’t help you a ton with plot or character. But having a single image and trying to build out from that to explore that fascination or obsession—I find it very exciting and hopefully it ends up making the character and the plot organic. I don’t think it’s a very efficient way to do it. But efficiency is not the point.

HL: I wanted to talk about dopplegängers in your work. There are so many all over the place, in your short stories, and in The Beautiful Bureaucrat, where all of these women who sort of look like Josephine (the protagonist) work in offices that sort of look like hers. Even in And Yet They Were Happy there are stories that have the same title, that are differentiated by numbers—almost like we’re all one in a series. What is it about the uncanny space that’s created between two dopplegängers, or two twins, or two similar things, that’s fascinating to you?

HP: I think the idea of dopplegängers brings up a very natural question about identity: is your dopplegänger the ultimate threat to your identity, or is your dopplegänger your ultimate collaborator? I really do think of it that way. And I think this is asking a broader question, because we spend a lot of time noticing the differences among people, and I’m very interested in the similarities and the common ground. I appreciate that everyone is a unique snowflake, but I also appreciate that there’s a lot of shared ground in human experience, in terms of losing a loved one, or becoming a parent, or falling in love, or falling out of love. I’m interested in the ways these human experiences would be familiar to a lot of people.

HL: In your story “The Joined” we see this planet where everyone has a perfect match waiting for them. It’s amazing how threatening it is and also how liberating. It becomes an ultimate goal to find your match on this planet. There’s a kind of danger that goes hand in hand with love, or acceptance, or finding your place.

HP: In “The Joined” this couple realizes that they can find their perfect hermaphrodite match—yet they end up choosing their imperfect human relationship. And this is not unlike in the “MyMan Solution,” because why not bring up the life-sized male sex doll? At the moment when he stops being the perfect man, and becomes imperfect, that’s when the narrator starts to love him. So I think there is something about this idea that you don’t love someone for the ways in which they’re perfect, you love them for the ways in which they’re imperfect. That’s where you get a foothold for love: seeing someone’s vulnerability, their little weirdnesses.

HL: I wanted to ask about the wordplay in your writing. I’ve heard you talk about it in interviews before, but what is it about that playfulness that’s so much fun for you? When did you start playing with language in that way?

HP: I’ve always been interested in words. I remember as a kid being fascinated by the word raise. That it means opposite things. You can raise something up, or you can raze a building to the ground. I think that language is this arbitrary thing, and when you find these little chinks in it, these little contradictions, it kind of unveils the whole system as a bit imperfect.

For some reason I’m thinking of Blood on the Tracks, the song “Lily, Rosemary and The Jack of Hearts,” when Bob Dylan mispronounces the word precious as press-ish. It’s my favorite moment in the album, because it’s a glitch, and witnessing a glitch feels intimate. I always felt this real longing in the gap between the correct and incorrect pronunciation of that word.

Language is trying to represent reality, and it can’t always do it. There’s no good language to describe what it feels like to lose someone. There’s no good language to describe what it feels like to become a mother. And wordplay is a way, for me, of acknowledging the failings of language. Hopefully by acknowledging it, language ceases to fail as much.

HL: When you play with language on the page, specifically in The Beautiful Bureaucrat— where there are long trains of words becoming other words and breaking down to their syllables—is that you trying to describe the indescribable?

HP: Yes, there is something more serious going on in those passages—but it’s also playful. It’s also joyful. It’s also: look at this mud that we as writers and readers and humans are surrounded by all the time, that fills our minds, and oh look, it’s as malleable as clay, we can mess around with it. In The Beautiful Bureaucrat—and this is a bit of a spoiler—I was trying to figure out how a voice would speak if it had no context. How would a person speak in the very earliest phases of existence? And what I came to was a voice that has no prior relationship to language, that feels playful with language.

My children play with language naturally, and it’s a thrill to see them. Whenever my son sees a fire truck, he really wants to see another fire truck immediately, and obviously we can’t make another appear. So we’ll say, “You have to hope to see a fire truck.” And so he’ll hop. He thinks we’re saying hop, not hope. And I think, oh, hop and hope, they’re kind of similar words. They’re kind of similar things, aren’t they?

HL: You’ve written a middle grade novel as well. What was that like in terms of this playfulness? Did you have to approach language in a different way?

HP: One thing that my agent said to me really early on when I was working on that book—because I was very preoccupied with questions of “do I have to change my language, my vocabulary?”—was “no.” She said you don’t have to. Kids don’t like to be written down to. And it didn’t end up feeling different, in that regard. My narrator was a twelve-year-old girl, and so you have a different kind of narrative voice to some degree. But it felt easy to access, and I did not clearly separate it from my other work in terms of the voice or vocabulary.

That book was very different for me because it followed And Yet They Were Happy, which was a collection of 340-word stories. They’re all exactly 340 words. Aside from that one rule, I allowed myself to do anything. So I could have characters from different time periods interacting, and figures from pop culture or mythology, usually in the interest of illuminating one particular image or scenario. There was a plot in each of the stories, but there wasn’t an overarching plot. Coming out of that project, I wanted to do the opposite thing. I really wanted to challenge myself: “Can I do a plot with a mystery and characters?” So the middle-grade book was very different from my other work in terms of creating an arc. In The Beautiful Bureaucrat I was actually trying to do both. I wanted the plot, and the building action, and the characters. But I also wanted the mystery, and the sort of abstraction. The more existential mystery. And the focus on language.

HL: Do you often set up structural constraints for yourself? Where did the idea of 340 words come from?

HP: I’m very interested in the way that something really arbitrary and almost bureaucratic—like saying every story will be 340 words—is ultimately liberating. The void is terrifying. Confronting the void with one, tiny weapon, like, “I’m going to use 340 words,” or, “I have to have a mystery story involving children,” it’s a little weapon. Or maybe that’s too aggressive. It’s a bridge—

HL: I like weapon.

HP: Weapon, sure. To go forth into the abyss. And to not be overwhelmed by it. So with every project I write, yes, I definitely have some kind of explicit challenge I’m giving myself. And that challenge is usually something that will steer me in a different direction: that’s how I stay interested and passionate. As a teacher—I teach at Brooklyn College—I always have my students do this kind of thing. One of my favorite assignments is [to] have my advanced students create an obstruction for themselves that gets at whatever they feel is their weakness. So if you feel like you’re bad at writing dialogue, okay, write a piece that’s entirely dialogue. Or if you always write realism, okay, write a piece of science fiction. And the students typically find it the most challenging and most rewarding assignment of the semester.

HL: It means so much to have that single hinge on which everything else in a piece of writing can happen.

HP: And then you don’t freeze up.

HL: How did Some Possible Solutions change over the course of the ten years you were writing it? How did it become the book that it is?

HP: When you’re putting together a short story collection, there’s so much moving around of the stories. To give you a little insight, the very first short story I wrote for the collection was “The Joined.” And the very last one was “Contamination Generation.” It’s not ordered that way in the book, although “Contamination Generation” does happen to be the last story.

“The Joined” was a life-changing story for me to write. This idea was knocking around in my head, “what if we could find the planet to which Zeus banished our hermaphrodite ancestors?” Then I had this image of a couple living in a kind of dystopian, urban environment. And I thought in order to do justice to all of this, the mythology, and the alien planet, I’d have to write a novel. And then I was like, maybe not. Maybe I don’t have to write a novel! And so I just sat down and I wrote it as a short story. I gave myself permission to do that. That story was a launch pad for me to give myself permission to say, “Okay, I can write a short story that has this much stuff in it.” Or a short story (“The Knowers”) where a woman learns her death date, and then I go through her entire life, and it’s ten pages long. “The Joined” was the first story where I brought in images of science fiction and mythology in one cohesive piece. So it was a landmark, watershed moment for me. All of the other stories inSome Possible Solutions flow from that epiphany. I want to write short stories that have too much in them, even though they shouldn’t have all of these different things in them. I’m just going to do it. Then when I’m writing them I never get bored because, there are aliens! How can I be bored?

HL: I want to ask more about the sci-fi elements in the book, and your influences. The story “Flesh and Blood” reminded me of this cult movie from the ’80’s called They Live. It pivots on this X-ray vision element, where some people can see what certain people really are underneath, and they’re these gruesome, skeletal zombie aliens. It’s great! The imagery in your story felt very much pulled from that world to me. And I was wondering, where do you mine for ideas? Do you read a lot of science fiction?

HP: I’m not really well read in conventional science fiction. Someone like Kurt Vonnegut is a big influence. Ursula K. Le Guin. I’m certainly influenced by people like George Saunders, literary writers who are straddling that line. Kelly Link and Karen Russell. I feel like I read a lot of science fiction as a child. Madeleine L’Engle? I don’t know if that really counts as science fiction. But those books that I would gobble up as a kid, series I can’t even remember the names of, they’re in the mix for me.

HL: How does liberating your stories to include these elements open up your fiction?

HP: I think it’s mainly about metaphor. It’s mainly wanting to draw on different imagery in the interest of saying something that’s very much about the world as it is. I could write a story—and I’m sure someone else could write a story very beautifully—in which someone in a completely reality-based world speculates about her own physical fragility, and the fragility of her parents, and everyone around her. But for me, it feels like a more visceral expression of that if she can actually see through people’s skin to their bodies, and witness their organs, and witness her parents’ organs, and witness her own organs in the end. A lot of times it just feels more visceral to me.

HL: Yeah, literally!

HP: Yeah, quite literally in this case!

HL: There’s a recurring theme of the known and the unknown in your work. In the story “Flesh and Blood” there’s all this stuff underneath our skin that we’re so close to, that we can’t see on daily basis. Then when your narrator can see it, the world kind of becomes unlivable for her. In “The Knowers” there’s this big question: do you want to know when your life will end? Part of being human is that you don’t know. So how does knowing the ending, which is supposed to be unknown, change your experience of everything in the middle?

HP: I like what you say about “Flesh and Blood:” that when you know, the world becomes unlivable. There’s a threat of too much knowledge. I feel like this goes back to Eve and The Garden of Eden. We have positive associations with knowledge, but of course it’s the Tree of Knowledge that causes all of the problems. Knowledge is dangerous. I get that.

I’ve been getting these alerts from New York City, or State, [that] say something like, “Tomorrow is an air quality advisory for all of New York City. Active children and adults should avoid being outside between 11 AM and 11 PM.” And I find these notifications somewhat horrifying. Do I want to know that there’s an air quality advisory, or do I not want to know that there’s an air quality advisory? I think that ultimately, I do want to know. As much as knowledge is terrifying and unpleasant, and ignorance is bliss, and we want to bury our heads in the sand, we should seek knowledge. You can live a better life when you seek knowledge. Though the world is almost unlivable when [the narrator in “Flesh and Blood”] can see through people’s skin, it also makes her life deeper and richer to have this awareness of her own fragility. Death is the spice of life. If we weren’t going to die, we wouldn’t appreciate this brief time we have.

HL: I was thinking about this too in the way it relates to how we talk about writing. “Write what you know,” versus “Write what you don’t know.” These kinds of phrases we throw at writers and at students. When you sit down to write these stories, how much do you know about where they’re going? And how much is unknown to you?

HP: Writing for me is a process of trying to understand some feeling or experience I have that’s creating tension in me. I don’t like that advice, “Write what you know,” I think that’s very limiting. At the same time, a lot of times, I write very close to myself. I guess there’s another phrase, “Write towards what you want to know,” and that resonates more with me. What metaphor can I use, what image can I use, what scenario can I use to explore and maybe ultimately lessen this tension that I’m experiencing about this particular issue? So writing is a process towards greater knowledge, or greater self-knowledge.

I feel like things are very unknown to me when I write. Very unknown. I believe it’s Amy Hempel who said she always knows the last line of her work. I find that so fascinating. I always know the first line, and I love first lines, and I love the way they’re portals and how you can make such big promises in the first line. But for me so much of the energy comes from [asking], how are you going to get from the first line to the ending? What will the last line be? That’s not only the arc of the story, but it’s also the arc of my writing experience.

HL: I feel like you can almost tell when a writer is writing a story that way. There’s an excitement there, upon discovering things, that the reader feels, that I don’t think you can fake.

HP: I think it comes through. I always feel shocked when I’m writing something. Oh, how amazing that that element came in! I never could’ve predicted that.

HL: What contemporary writers are you reading right now who you’re really excited about?

HP: I’ve really been excited by some of the nonfiction from people like Maggie Nelson (The Argonauts), and Eula Biss (On Immunity). Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams. I am interested in the lyric essay genre. I feel like my writing straddles different genres in a sense, and I’m interested in the fiction/nonfiction border, poetry/fiction border, scholarship/fiction, scholarship/poetry, criticism/poetry—just drawing on all different realms of knowledge in pursuit of more knowledge or understanding. Right now I’m reading Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler. I just read Fever Dream by an Argentine writer named Samanta Schweblin—it’s coming out next year; it’s a book that I blurbed. I had a physical reaction to this novel, and I’m obsessed with it, and I think about it all the time. I hope everyone reads it because I think it’s one of the weirdest, most powerful things I’ve read in a long time.

HL: And what are you working on right now?

HP: [The Beautiful Bureaucrat and Some Possible Solutions] have come out so close together that it’s been two years of editing and publicity. It’s been intense. It’s been very fun. But now I’m excited because I’m heading back into the cave and working on a new novel that’s about motherhood, but in a crazy way.

HL: Is there any other way to write about motherhood?

HP: No, there’s no other way!

Helen Phillips is most recently the author of Some Possible Solutions (Henry Holt, 2016).

Hilary Leichter is a 2015 NYFA Fiction Fellow living and writing in Brooklyn, N.Y.