By ISSA QUINCY

This piece is excerpted from Absence, out now from Granta (UK), and forthcoming from Two Dollar Radio (US) on July 15, 2025.

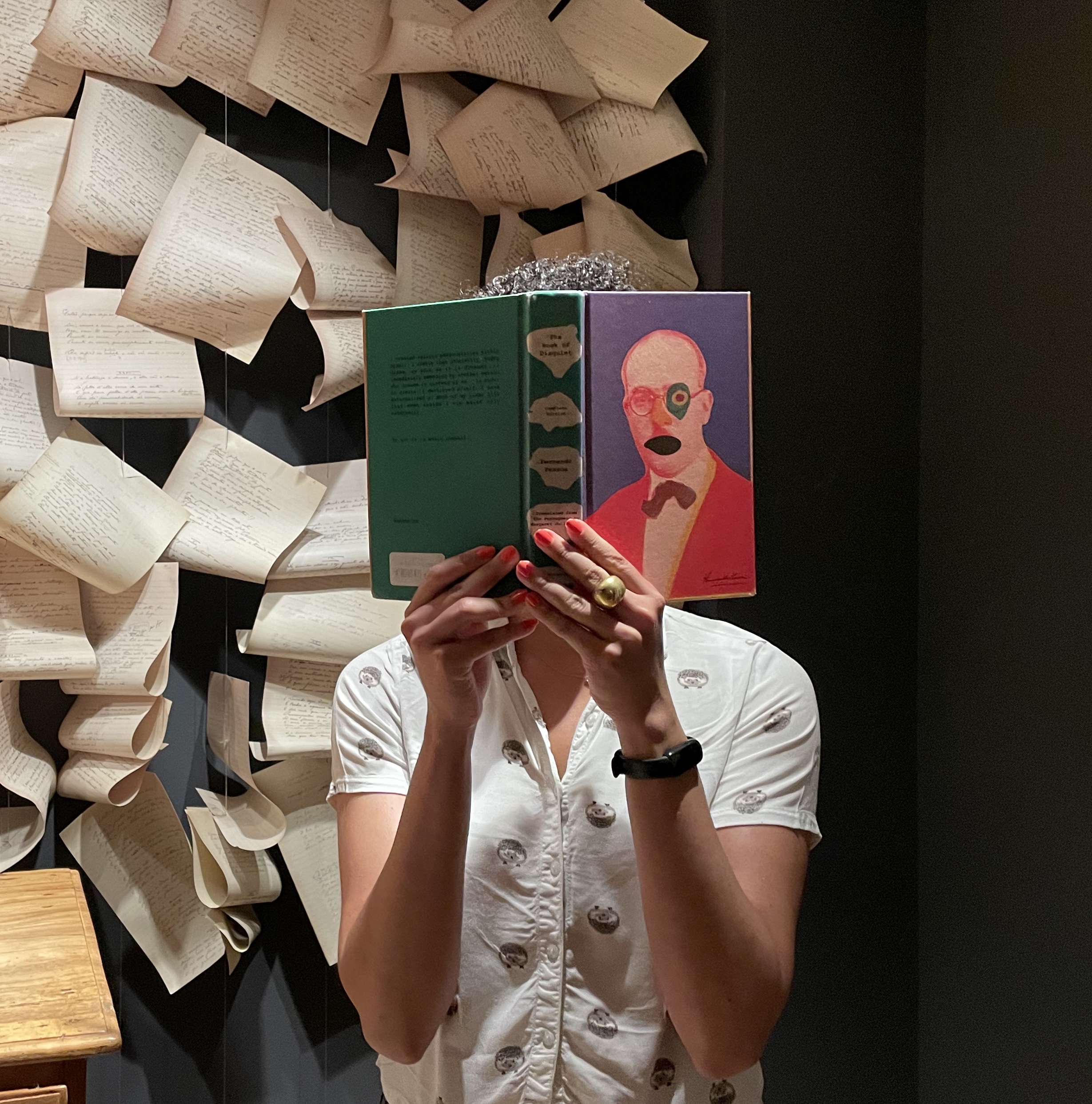

In the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, there is a painting by Hendrick Avercamp, the mute of Kampen, hung on a deadening grey felt and squeezed in amid other Dutch masters. One’s initial glance at the painting will see it reveal little more than a benign winter scene. However, when you look at Avercamp’s painting closely you begin to notice the close detailing of the variance of life. There in the painting exists death, pleasure, ecstasy, frivolity, poverty and secrecy, closely exacted alongside other states of being and non-being all perceived by Avercamp from a heightened position, a vantage point for an incorporeal observer; a drifting onlooker that watches and takes in the immediate while the rest of the yellow-grey land and sky disperse outwards into misty incomprehensibility. What is presented is the sight of the intangible spectator that sees what is in front of him, recognizes everything and curtails his judgement of anything.

In Eastern Massachusetts, there are three identical buildings that protrude out of the soft brown earth. They are dense redbrick high rises. Each one perfectly equidistant from the other. Along the face of each building is an endless number of windows that on certain days, in certain lights, with the sun shimmering off them, seem to ripple like great red undulations flashing as you drive in their shadow.

This was not how I first saw them.

When I was seven years old, my parents made a doomed and brief move to Boston; for work for my father, to be nearer to her family for my mother. This move would only last three years, and resulted in my parents return to England, and their divorce that same year. In that time, however, when my mother and father were busy, I’d often be left in the company of my grandmother, whom I frequently accompanied in car around town. When going to either the cinema or the grocery store we’d drive to Fresh Pond Mall. To get there, we wound down tree-lined streets, verdant suburbs and on past old and newly painted colonial houses with damp wooden facades and Boston-blue trimmed windows to eventually arrive at the shopping centre from behind, not from off the Alewife Brook Parkway, not from past Fresh Pond itself – an old pond from which Native Americans would fish for alewives and drink from, a pond which you can skate on in the winter.

When you arrive at Fresh Pond via the back entrance you must drive across an overgrown portion of abandoned railway line that was once a part of the Watertown Branch Railroad. In the autumn, you can follow this trail round through Cambridge, and with the shimmering leaves scattered around you, you feel warmed by their fervent colours even against the bite of the sharp Atlantic air, like you’re ensconced within the roar of an ancient funeral pyre.

It was snowing when I first saw the towers. I remember the day as being emptied of life. Thick snowdrifts were piled high on the roadsides and an ice-thin wind whipped around me. I remember scowling as a young boy at the sight of the towers, believing them to be miserable and seemingly abandoned, despite knowing little about them. When I think back to it, or rather when the images resurface in me thoughtlessly, the disturbance I felt at seeing the towers I now know related less to the immediate structural nature of them and more with the looming symbolism of refuge, endless corridors and hidden lives consigned to the silently suffocating margins of this world. The feelings of imposition and silence, more cognate than we think, are ones that have haunted me since and continue to, even now. I believe that this nauseate moment as a young boy was the source of these sparring powers that have beleaguered my thinking since.

The fact that the buildings could elicit such an immature revulsion and wonder in me as a young boy spoke to the imposing power of these looming structures. Often, from the backseat of her car, I would ask my grandmother why they had even been built in the first place. For people to live in, she’d respond, but this answer, which she would repeat to me each time I asked seemed both detached and uncaring and in some way to be lazy; an obvious answer that didn’t reveal to me what I hoped it would despite the fact, of course, she was right. As a boy, I could never make sense of the towers, like their very presence sat contrary to the land that they occurred of. It seemed they had erupted through deep fissures in the ground, steaming up from the hissing depths of a terrain entirely unlike the one they now domineered.

After finishing school, little more than a decade after my boyish judgement of them, I moved to Boston to work for a year, and the three towers came back into my view. At the time, I was working as a kitchen porter in a narrow restaurant called Les Sablons in Harvard Square. The restaurant, an old MBTA bus terminal, had been repurposed into a French eatery. Buses still ran past it, stopping and starting beside it, and there drivers changed shifts, some pausing for a smoke and a conversation as if the altered interior of the building hadn’t at all changed the operation that had for so long run within it.

February 2004

It was quiet at the restaurant. I had taken a smoke break and come out from the heat of the kitchen into the snowy evening when I asked a woman sat in a faded blue bus driver’s uniform on a bench for a lighter. You’re British? What the hell you over here for? she cackled as smoke seeped through the gaps in her teeth, revealing one or two gold crowns.

She was a weathered woman: her life written into her skin in the etchings of her smiles and the lines of her frowns. She wore her hair in carefully maintained coiling curls that bounced just above her shoulders and a gold Cuban link chain with a Jesus-piece pendant turned the wrong way on her chest, his callow and mournful expression shying away from me, nestled into her bosom. Beneath photochromic glasses, her eyes studied me vaguely. Patricia, or Pat, was her name. She was a bus driver for the MBTA. I was born in Harlem, she explained, and grew up way up there on 151st street, the Harlem River houses. I came here to Boston about thirty years ago now. With my son. When I asked her why she left, without hesitation and in a stony and resolute voice she said, I didn’t have a choice. It was dangerous for me. It was dangerous for my son. I couldn’t tell no one there. I just had to go. And one night, he was out, I don’t know, working or drinking, something like that. I took my son and we upped and left, got on the coach. We didn’t look back. No one knew. We just had to go. She then paused and softly said again, There wasn’t a choice. It was . . . What they call it? a wry grin suddenly curling across her face, A matter of safety, she said mimicking my British accent before chuckling to herself.

I clearly remember that even with her incessant smoking (a carton of Marlboro Lights a day), which had grazed her voice down to a hoarse drone, she managed to maintain the fragrance of a sweet and sharp perfume that I subsequently discovered to be ‘1000’ by Jean Patou. Patricia would later tell me that they had discontinued it, and that when she found this out she went online and bulk-bought as much as she could. And even then, over a decade after it had stopped being manufactured, she’d find herself trawling through eBay and outmoded webstores for any lingering bottles.

When I first smelt it on her an odd sense overcame me. It was the scent of paling summer evenings spent at dinner tables as a bored young boy listening to the drone of adult conversation circling around. Where distant and alien-sounding regions like Helmand and Basrah and words like fiscal and unjustifiable were frequently uttered and re-uttered with increasing fury long into the night. And as well, upon smelling her perfume, I found myself lost in a memory (that I can’t be sure was not a fabrication) of being sat at my grandmother’s house as a boy, leaning wearily into a garden chair, my gaze fixed on the tree swing wobbling in the wind as uncles and family friends fumbled over a grill. A breeze would blow and I’d become cold and slap the mosquitoes on my arms and legs as I lay there happily watching as the gathering evening that had lengthened around us became punctured by the starry glints of fireflies.

Those thoughts, however, were washed away by the sudden blue-black darkness outside the restaurant, as well as the conversation that had ensued between Patricia and me as we shivered in the soft and vanishing snow. I told Patricia that I had finished school and was working here before I hopefully would be able to continue my studies somewhere. But tell me about England, she said with a smile, I wanna know about London and where you grew up. I’ve always wanted to go there. Believe me, I will soon. And what about this restaurant, any good? I heard it’s expensive. I gave her the answers that I gave everyone: mechanical ones that I had perfected in the time I’d spent there like they were the lines of a script.

Despite all the distractions of the evening and the transience of our encounter, I didn’t forget the first sense I had when I met her and smelt the perfume she wore. I had been overcome with indiscernible feelings, scattered memories and images that I couldn’t piece together. It is true, to some extent, that her smell nudged at something in me that I wasn’t yet sure of and called down to some forgotten part of me. It’s my only luxury, she would later repeat defensively to me whenever the struggle of living costs arose in conversation, It’s my treat to myself.

Years before, Patricia had come into contact with the perfume through an old lady who would take the bus from Harvard Square to Fresh Pond to feed the ducks each morning. After almost a year of her boarding the bus and the two of them talking, Patricia asked the elderly woman which perfume she wore as she liked the scent. The old lady refused to tell her, saying with a wink, Not until I am closer to death. And when one morning, five years after first getting on, Patricia helped the old lady – who was by this point immeasurably frail and required a carer to attend to her – off the bus, the old lady whispered, Patou ‘1000’. Patricia knew naturally that would be the last time she would see the old lady and it was. For Patricia, wearing the perfume felt like A kind of inheritance.

In the time I worked at Les Sablons I came to know Patricia more as our shifts and breaks began to align; much like when there comes a certain natural, biological alignment in the early stages of a symbiotic relationship, one that seems entirely organic but is in fact willed into being from both sides, either unconsciously or consciously.

You remind me of my son, Patricia told me one afternoon, You aren’t like him . . . But you remind me of him . . . It’s something in you. I don’t know what. Patricia told me she wasn’t in touch with her son. She never told me anything more. His name. His age. Anything. She only had had one boy. She never told me what had happened between the two of them and I never asked, as to me there remain certain things, many things, that do not require words to be understood: the change in her gaze, the contortion of her posture, the manner in which her smile would fade and silence seeped into her person whenever her thoughts distracted her and they were only of her son. All this quietened my own curiosity like the silence I kept granted her the space she didn’t allow herself.

Often Patricia and I would talk about the news. She would lament the escalation of prescription opioid usage that she saw quietly, even then, as a problem in her community in Boston, and with each passing ambulance she would say, There goes another off them fucking pills, with a kind of matter-of-factness and disdain.

I remember arriving at South Station late one night off a Greyhound bus. It was around 3 a.m. and I wanted to buy a carton of cigarettes. Because of the recently changed laws, I was no longer able to legally do so, and so instead I cantered around the station looking for someone old enough to buy them for me. Outside, beside two backpacks resting against the wall, I spotted two young men leaning on one of the exits at the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Summer Street. One was considerably younger than the other. The older one smiled and approached me for some money.

I asked the older one, offering him whatever change remained from the purchase, to buy me the cigarettes and together we walked to the nearest store. The man, Patrick, had just turned twenty-two and was broad-shouldered and appeared physically fit. He and his younger brother – who by contrast was a quiet and cowering boy – had returned from a retreat in upstate New York. Patrick was handsome: he had cropped ash-brown hair, cutting cheekbones and was tall. It was only the smut that covered his cheeks and brow, the thick-tongued speech and the state of his clothing, fraying and sullied, that gave away the nature of his problems. I asked him about himself as we proceeded on our walk along Summer Street to a nearby 7-Eleven whose lights painted the tarmac outside in a lurid white light.

My brother and I are from Gloucester, Patrick began, our parents still live there, right out on the coast, just beyond the city. You know it? It’s beautiful there but there’s not much to do. He paused and turned back at his brother, who was leaning against the station wall, before eventually admitting to me, We’re trying to get back home. Back from where? I asked myself. Why couldn’t they get back home? What had happened between their parents and them that meant that these two young boys were trying to find their way back home? What had led them to find themselves as dishevelled as they are now? And as our conversation continued, more questions flooded my mind. Why was it that their parents had refused contact with Patrick and banned him from their house? Why did Patrick talk with subtle traces of disgrace when he mentioned his parents? Was it that he thought of his father calling him a sickening disgrace? Or, a stain on this family? Or was it that he knew his parents felt threatened by him, much bigger than them both, as after an argument years ago now in a drug-addled rage, he reached for his father’s gun – was that it, the final straw? Or was it that he knew they couldn’t bear to look at him for what he’d turned their youngest son into? Or was it that like him, they felt an implacable pain each night when they thought of the time before then, and that they were forced to reflect on what in some way they felt responsible for? But that distance – that is ever-extending yet not as wide as we often feel it to be – helped them cope with their dreams, their terrors and the quieter times when one of them would stumble across a photo of their eldest and forgive him, deep within them, forgive him a thousand times but never in actuality permit themselves to; leaving them all, the two boys, the two parents, to instead walk the earth separated, divorced from each other but full of crumbling thoughts of the other, all only wishing that that distance they had cemented over time would one day collapse.

Our family run a landscaping business there, Patrick explained. Over the summers, I would work it with my dad and uncle. In the evenings I’d go to football practice. My little brother wasn’t sporty like me. I was always a sports player, you know, that’s the way dad wanted it, he went on, clearing his throat, even from when I was young, like five or six, I played football. Dad pushed me to do it. I wasn’t too big on it at first, didn’t really mind it much, but there wasn’t much else going for me. I used to like doing landscaping: the pruning and gardening especially. I always said if I don’t do football, I’ll have my own landscaping business. When I got to Amherst, I was playing Division One and was doing good there, until my sophomore year when I broke my ankle pretty badly, snapped some ligaments and it was sorta’ rough for me from then. I was prescribed pills, Oxys, to deal with the pain. I finished my course and moved on to something stronger. Struck by his sincerity, his totally affectless words, I asked about his brother. I was shooting up at my parents’ house, he explained, in their basement. I don’t know how. I don’t remember too much if I’m honest. I don’t like to. But my little brother got hooked too. He was fifteen at the time. Now he’s worse than I am. I don’t like to think about it if I’m honest. After buying me the cigarettes, we walked back to his brother and each of us had one. The younger boy didn’t speak but smiled with a beautiful and admiring timidity at whatever it was Patrick spoke of. I stayed with them until the conversation petered into silence then left them with my cigarettes.

After this encounter, whenever I would see an ambulance and Patricia would say, There goes another one, I would quietly believe it to be one of those two brothers, imagining one of them overdosing as though it was some cruel inevitability that had been fated by the blankness with which Patrick explained his tragedy to me. Making it seem that he knew before I did that death or near-death was to be the singular consequence of our encounter, that there was no use in systematizing a preventative strategy, that as far as he was concerned things were decided and simply barrelling, or dawdling, along to their unfussy end.

When I thought of it, I always imagined it to be Patrick first, but it was some months later that I saw a framed picture of his younger brother on a local news station, with the same self-effacing and quiet look I had seen in the dead of night outside South Station, held in the shaking hands of an inconsolable mother stood outside the gates of a pharmaceutical company, surrounded by a pack of sullen faces, young and old; a mother who couldn’t help but feel the full and oppressive weight of responsibility that had, in the days and weeks since she heard her little boy had died, pinned her to her bed, leaving her to linger in a lifeless and thoughtless pain. A feeling that was too strong for her to give words to and too absolute to remain in silence over. She, from then, would live in that strange position I have found so many of us having lived – pressed between a piercing howl and an irreversible silence.

In between working at Les Sablons, I spent my hours in a Dunkin’ Donuts tucked beneath a parking garage. There is something to be said for the anonymity conferred by franchise spaces as though it is the rigidity of their form, the immutability of their interior, that translates a similar kind of invisibility onto the passing faces that enter. I first experienced this sense in this Dunkin’ Donuts, or at least became aware of it, as I found myself unthinking for a moment and comfortably unnoticed. For each second my body was asserted as it was, it was simultaneously waning in appearance until soon no eyes inspected me, no one cared, no one questioned my figure, no one scrutinized me. I was there, so present, so accepted and so unheeded, that just as much – I was not there. I remember explaining this feeling to Patricia excitably and her laughing at me. Embarrassedly I asked why she laughed and still chuckling she explained, All I ever wanted was to be seen, to be heard.

Patricia often complained to me about her job: I’m gonna leave soon. I’m done with all that shit now, but she never did. It seemed the more she spoke about it, the less her conviction to do it meant anything and each time I asked her why she continued to work as a bus driver despite loathing it, her face would drop and she’d hastily cobble together a different answer made up of the same old words.

We’d sometimes take long drives in her old grey Subaru around Boston and she’d sing croakily along to whatever played on WHBR, the smoke from her cigarette mixing with the cold Boston air, blustering specks of ash onto the back seat. Sometimes, we’d stop somewhere for coffee and she’d tell me about the cities that she wanted to visit. The one in particular she kept talking about was Edinburgh in Scotland. I’ve seen photos of it, she’d say, I would love to go, and assuming the role of worldly traveller that I felt she wanted of me I would tell her about the Royal Mile, spitting on the Heart of Midlothian where the Old Tollbooth had once stood and of the network of tunnels and vaults that run beneath the city. And she’d listen, quiet, still, sometimes with her eyes closed as I spoke, imagining herself there.

One evening, near the end of my time in Massachusetts, Patricia invited me over to dinner at hers, I want you to see my boy. She gave me her address and in the quiet north-eastern evening I arrived from off the Alewife Brook Parkway and stood at the foot of the three towers that I had once scowled at as a boy, once questioned and scrutinized, unravelled and undone in my head, in disgust or confusion. Patricia told me that she had lived there as long as she’d been in Boston. When I first arrived, it was dangerous. I know it doesn’t look it now, but back then it was dark everywhere. I remember junkies in the corridors, slumped in the stairwells. At night, you could always hear somebody hollering. Someone always had to be shouting about something. Someone getting beat or whatever. The whole place had a different feel to it. But no one cared. The police, the housing authority – no one. It was like we were invisible in these towers. Which is crazy because you can’t ignore them, they’re the tallest buildings around. Anyways, that doesn’t matter. That’s what I’ve learnt, it doesn’t matter. No matter how tall, small, fat, wide or thin you are, you can still be invisible. And that’s what this place was and the people who lived in it – unseen.

The table was laid for three with a large dish of lasagne and a big bowl of salad. We began to talk and I waited for the third guest, but Patricia started on her food, so I joined in. He’s coming . . . He’s coming, she kept saying whenever I asked. The third guest never arrived. I stopped asking. After dinner, we sat in her brown carpeted living room, lit only by the glow of a naked bulb and a muted television which showed the news as Patricia told me about some of her experiences in the towers. As she spoke of her memories, she became increasingly apathetic and weary, as though each flicker of violence, tale of fear and single tear that welled in her eyes provoked a deep pain that till now she had prevented me from seeing, like giving words to the thing renewed its reality.

One such story I can recall in particular was of a young boy she watched be stabbed to death from her window. She told me of the flurry of shadowed figures floors below her as she pressed the phone to her ear to call the police. The words and images that she thought of caused her eyes to widen. It looked like a dance from up here, and required her to prop herself up on the couch when telling it to me. It was crazy, but as she spoke and explained it, I noticed her eyes couldn’t meet mine. I ran down to help, and this became so evident that I realized she was intentionally avoiding them. I didn’t know who it was, as if to catch sight of my face would cause her to cry.

From the eighteenth floor you could see all across Cambridge, right down to the Boston skyline, which the Prudential Center and the blue glass of 200 Clarendon Street dominated. As the sun slowly set, the shape of those buildings drew out into large vertical shadows on the land below. From the other side, you could see Fresh Pond perfectly. I imagined seeing it in winter, looking down onto the skaters. I thought of that old Dutch painting that still hangs in the Rijksmuseum and I wondered what Avercamp might have made of the distending cityscape from this vanishing height.

For the remainder of the night, Patricia spoke in a whispered voice. They didn’t do anything about it. It wasn’t in the papers, on television, no one was ever arrested, no one ever knew. It felt like me alone. I drifted off into thought looking at the glinting lights of the city below. When I went to the bathroom, I noticed a room with its door ajar and the light on behind it. Peeking through, I saw a single bed, perfectly set, the room exquisitely maintained, the books were as I imagined they always had been, sets of shoes were under the bed and pyjamas were perfectly folded on top of the duvet. When I returned, Patricia was asleep, and only then did I notice the huge spread of photos of her son that covered the walls around the television. There was a black-and-white photograph of two people, a young boy nestled into the bosom of a young Patricia on a street corner. I took it in my hand and on the back of it, in archival ink was written: Jesse and me, NYC. From his neck hung the same canted gold head she wore but this time it faced me. In all the photos, she was smiling as I hadn’t ever seen her smile before.

As she slept, I watched the view of the city disappear into darkness until it seemed that the clusters of houselights across Cambridge and Boston were constellations of stars. My eyes fell upon the exact point in the parking lot of Fresh Pond from which I had looked up at the building I now occupied and again my grandmother’s words returned to me, much as these very towers had too, For people to live in. Patricia was still asleep. I left her with a blanket over her and two weeks later, after finishing work, I returned to my mother’s home in Oxford.

Two years later, I received an email from the executor of Patricia’s will, a cousin of hers. She had passed away of lung cancer. He wanted to know what my address was in order to send what it was that Patricia had left me. I was surprised to know she had left me anything at all as we had hardly stayed in touch since I had left. But some weeks later, my mother came to my bedroom door and handed me a package. She stood in the door frame and watched me open it. Inside was a full bottle of her perfume – ‘1000’ by Jean Patou – and a scribbled note to me that I won’t share the contents of. Upon first seeing the perfume, my mother said in slight shock, I used to wear that perfume. And as though latent and lain dormant, deep at the ends of my body, a great burst of emotion coursed through me. I still cling to the thought Patricia sensed of the rising of childhood memories in me the first time I met her. I thought of her life, of her son, Jesse: two of the forgotten, left to die as they lived – unseen and unheard.

Issa Quincy is a British writer. His poetry has appeared in The London Magazine, New Rivers Press, and is forthcoming in The Atlantic. His fiction has appeared in Transition Magazine and The Kenyon Review.