In collaboration with Lateral Office

Introduction by Scott Geiger

The Faroe Islands are not the rural, subarctic archipelago you imagine. Like their distant peers on the Danish mainland, the Faroese are thoughtful, progressive city-builders. To connect their dispersed communities, their highway system tunnels through basaltic mountains and under North Atlantic waters. Fast ferries and helicopter taxis run between remote points. With such transit infrastructure, this might seem like a maritime metropolis, if only they had the population. But more people live in Portland, Maine, than on the eighteen Faroe Islands.

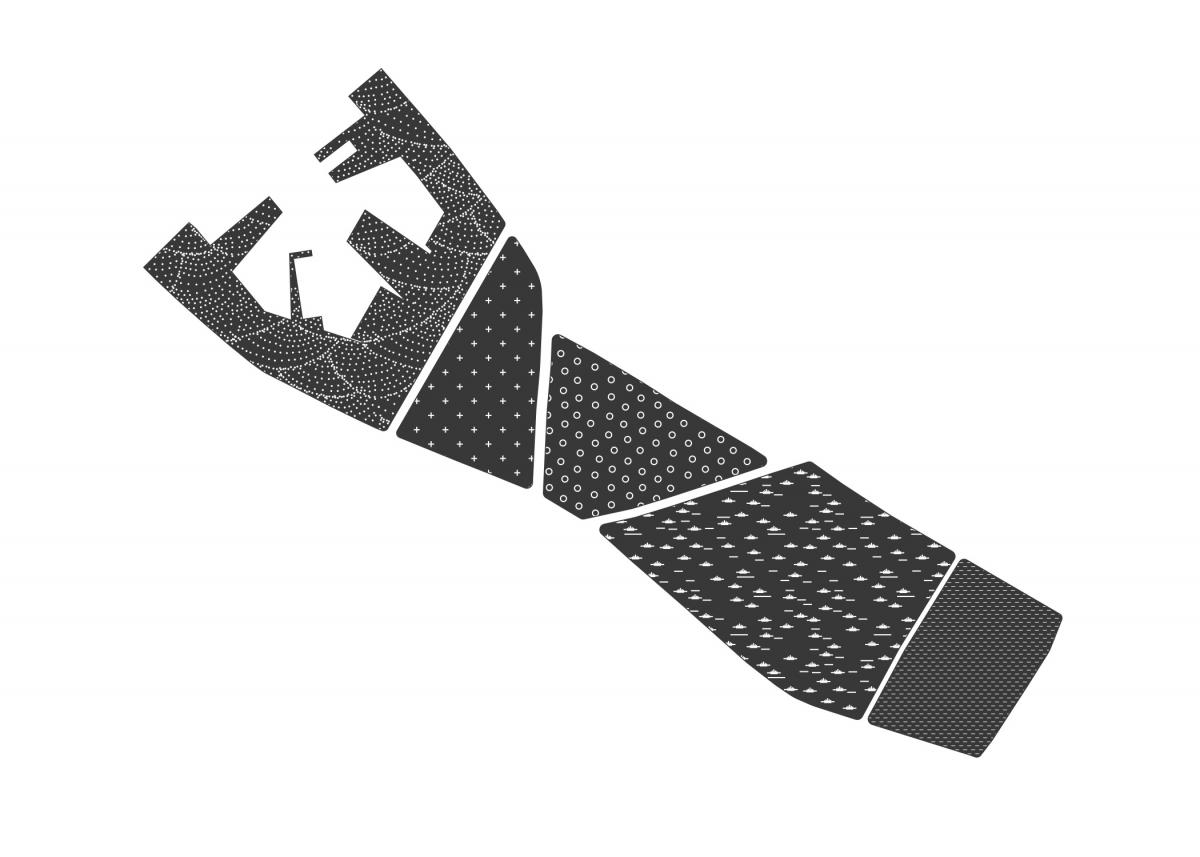

Two islands east, and a ninety-minute drive, from the international airport at Vágar is the island of Borðoy, home to Klaksvík. It has grown abruptly from a fishing village to the Faroese state’s second city. Five thousand people live pinched between steep mountains and two inlets. In plan, their city is shaped like a chromosome. Two long legs frame a significant working harbor with a modern commercial fishing fleet; the short legs wrap around the smaller south inlet. The nexus of land between the bays is Klaksvík’s historic center, but it has no public spaces, no destinations to create a sense of civic identity.

An international design competition in 2012 brought attention to Klaksvík’s urban future. Lateral Office, the Toronto practice of architects Mason White and Lola Sheppard, created their entry, “Peaks and Valleys,” in collaboration with Colombian landscape architect Luis Callejas. Notably appropriate for the challenge, this team of designers shares a view of cities as networks, continuous terrains rather than discrete buildings and spaces. Turning off these conventional expectations for architecture reveals critical insights and rich opportunities.

In a body of research about future development in the Canadian arctic, Lateral Office has shown how small, remote communities perform. Such populations live close to nature but quite often also serve a vital purpose to an economy or a society, from trucking to medical care. Luis Callejas grew up in a Colombia so volatile it could not afford to prize public space or landscapes. But in a succession of award-winning proposals for sites from Medellín to Kiev, Callejas has crafted inventive public spaces with sophisticated ecological designs.

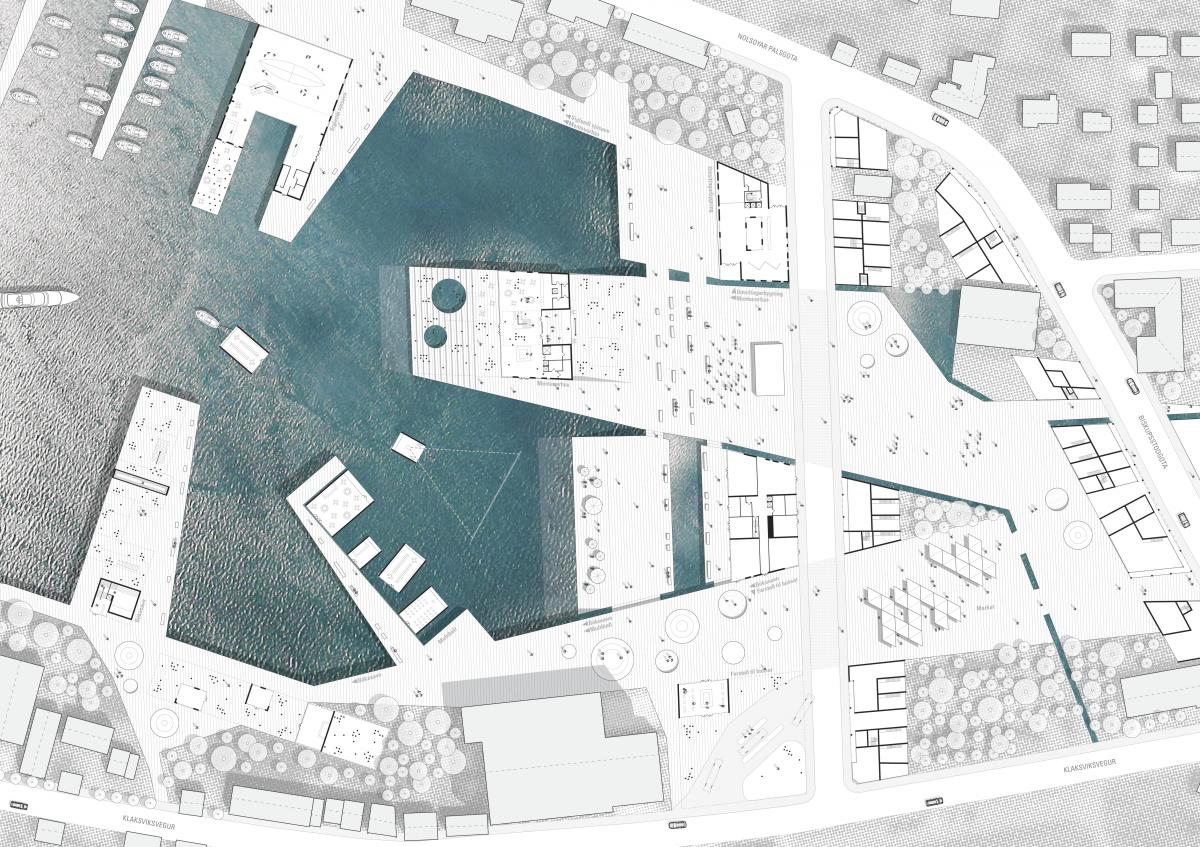

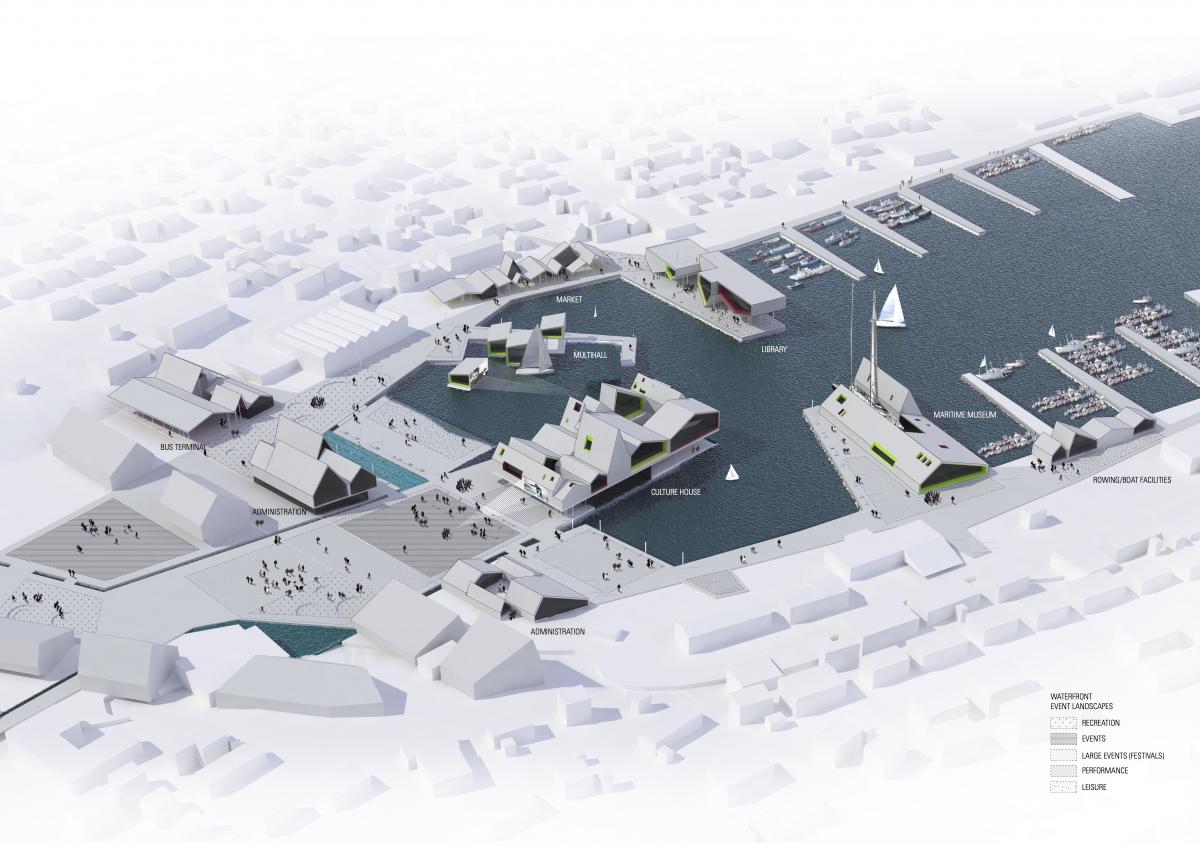

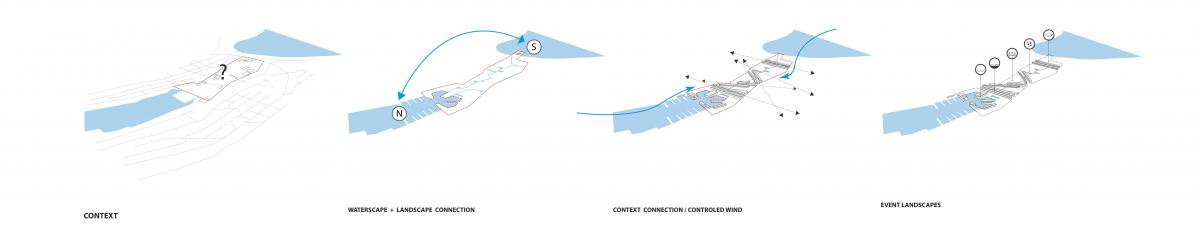

“Peaks and Valleys” begins with a reorganization of the present city center. A once-buried watercourse trickling between the bays is exhumed to become part of the city’s public realm. Key byways are oriented against typical wind patterns. Present-day Klaksvík has been built with wide gaps between buildings, even in the densest areas. To animate this abundance of space, the new streets from “Peaks and Valleys” frame five public landscapes, or City Rooms. Callejas places a Water Room around the Marina. The juniper and beeches of the Forest Room surround an elementary school.

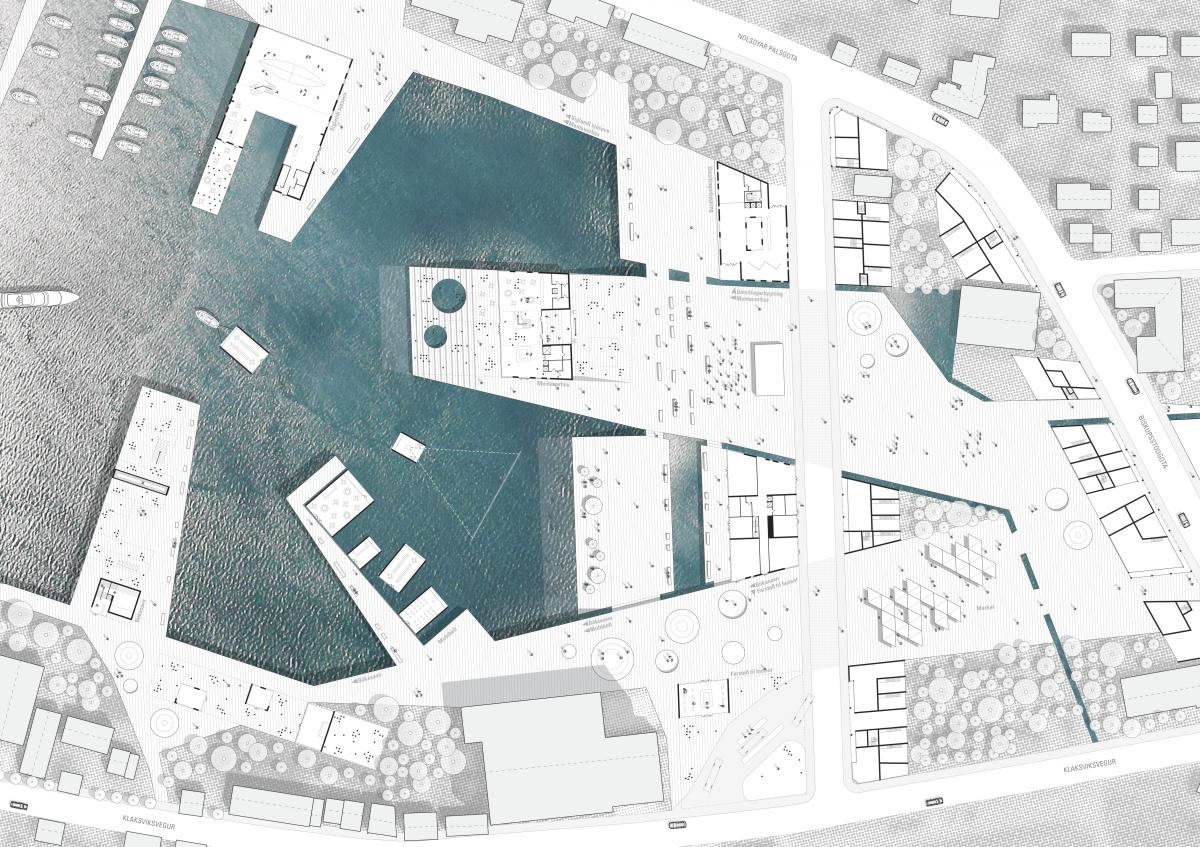

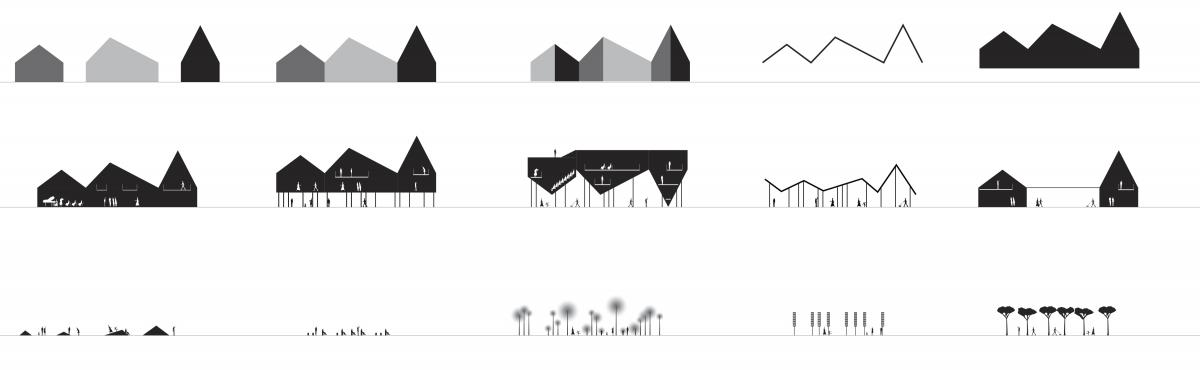

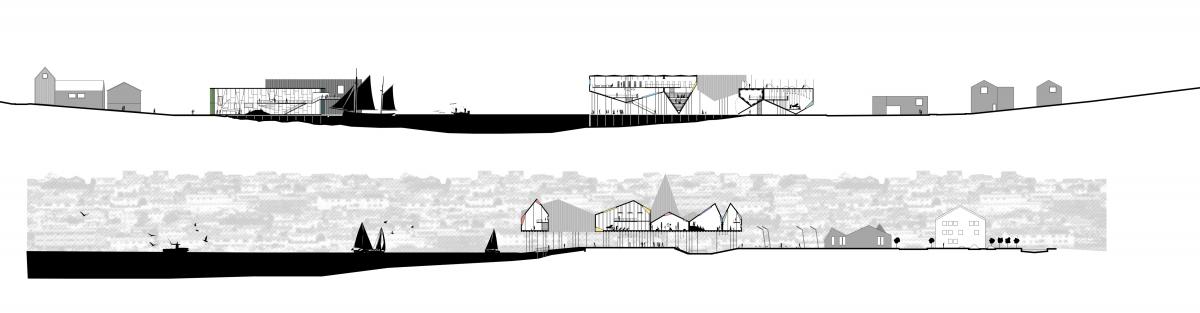

Geology and climate have shaped the human inhabitation of Klaksvík for over two hundred years. Their vernacular architecture is a wood structure, well insulated, with few windows and a tall, peaked roof. To offset the gray volcanic landscape and North Atlantic weather, the houses wear bright nautical paint. This vernacular has evolved to specialize in houses, not public buildings. Any new civic or cultural building in the city center should be generous enough to accommodate the entire community. Lateral Office has elaborated the Klaksvík house typology to increase capacity, extending each building to become landscape itself. Peaks on the roofs of the new city center buildings vary, creating a dialog between the historic buildings and the rugged countryside beyond. Window walls through the facades create views; apertures admit light through the roofs.

Lateral Office and Callejas place their new city center buildings around the edge of the working waterfront, forming what they call the Cultural Marina. The surrounding Water Room and adjacent Stage Room might be configured to host open-air festivals, public market days, summertime regattas, and concerts. A proposed new Klaksvík public library, elevated above the waterfront, becomes the city’s icon—an upside-down Faroese house, glazed on two sides. One imagines a reader looking up from a book to see into the city center or out to the North Atlantic.

“Peaks and Valleys” is sympathetic to the legacy of Faroese buildings, but it is not overly deferential to the past. This proposal looks ahead to a new kind of city for the developing world. In their work on the arctic, Lateral Office has described the idea of a hyper-vernacular that eschews all historic or imported architecture in favor of built environments completely customized for specific communities. As Klaksvík moves into the twenty-first century, it becomes more like itself than ever before.

Please click on the images for a larger view.

Luis Callejas is a Colombian architect, former founding partner of Paisajes Emergentes, and now director of LCLA Office. His practice is oriented towards new forms of public realms through environmental and territorial operations. Callejas is currently a lecturer in landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is also the author of Pamphlet Architecture #33: Islands & Atolls, published in May 2013 by Princeton Architectural Press.

[Purchase your copy of Issue 06 here]