EMILY EVERETT interviews XOCHITL GONZALEZ

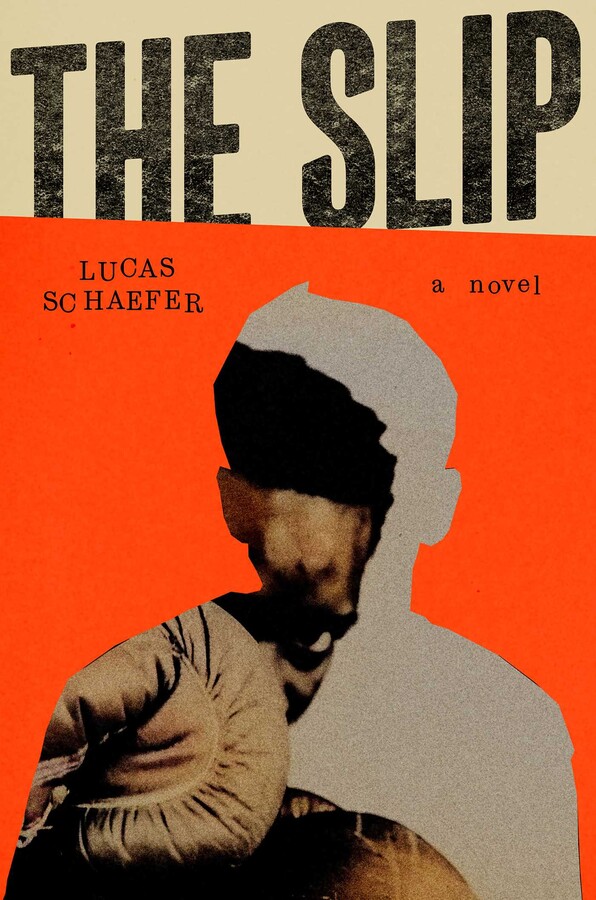

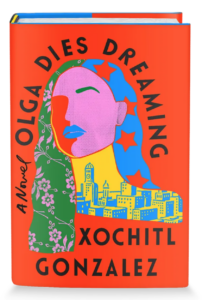

Xochitl Gonzalez has an MFA from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she was an Iowa Arts Fellow and recipient of the Michener-Copernicus Prize in Fiction. She was the winner of the 2019 Disquiet Literary Prize, and her work has been published in Bustle, Vogue, and The Cut. She is a contributor to The Atlantic, where her weekly newsletter Brooklyn, Everywhere explores gentrification of people and places. Her debut novel Olga Dies Dreaming is out now from Flatiron Books. Prior to beginning her MFA, Xochitl was an entrepreneur and strategic consultant for nearly 15 years.

Olga Dies Dreaming follows two successful siblings in Brooklyn: Olga, a high-end Latina wedding planner (drawing from Xochitl’s experience in that role) and Prieto, a rising political star. Abandoned by their mother, a Young Lord turned radical, they were raised by their grandmother in a Brooklyn that’s now disappearing under gentrification. They tangle with their own personal struggles—secrets, hurts, ambitions—until Hurricane Maria turns all eyes to Puerto Rico.

TC managing editor Emily Everett spoke with Xochitl via Zoom in August 2021, just before filming began on the Hulu pilot that Xochitl adapted from her novel, co-produced with Emmy-nominated filmmaker Alfonso Gomez-Rejon.

Emily Everett (EE): What can you tell us about the title of your book? It seems like a reference to something?

Xochitl Gonzalez (XG): It’s from a line in Pedro Pietri’s poem “Puerto Rican Obituary.” It was written in the time of the Young Lords party. He traces these characters—Juan, Miguel, Olga, and Manuel—all Puerto Ricans who came here and are now trying to be “Americans,” whatever that means. He traces how they start to feel ashamed. But they have these ambitions, these dreams. Olga dies dreaming of winning the lottery, or dreaming of diamonds. I just thought that was such a perfect title. It ended up having a larger meaning, when I think about her character and her changing ambitions. And I was also excited to pay homage to that poem. I feel like in some ways, in the last couple of decades, we’ve lost some of that legacy. The Nuyorican Poets Cafe is such a giant part of contemporary poetry, and yet the legacy of it hasn’t really been celebrated. So it’s a nice thing to be able to do that in the book title.

EE: So did Olga’s name came from that poem?

XG: I actually researched different revolutionaries. I thought that it would make character sense that Olga’s parents would name her after a revolutionary. So she’s named after Olga Garriga, who was actually born in Brooklyn and ended up going to the University of Puerto Rico and fighting for Puerto Rican liberation. And by fighting, I mean that there was a gag law. And so she was essentially putting up flags, and put in jail for that as a political prisoner. So that’s who Olga was named after, and then the dovetailing with the poem just happened to work out perfectly.

EE: I absolutely love a novel about family, and this, to me, is a true family novel. The dynamics between Olga and her brother, and between the members of the extended family, are richly nuanced, funny and warm, tense and messy. I loved all the drama with the aunts and uncles. Did you set out to write a novel about family?

XG: Originally, I only conceived of Olga. And then later, on the train to work one day, I thought, she should have a brother and he should be a politician. I think one of the things that I wanted to do with this novel was showcase the diversity that exists within a Latinx family, and I think, almost any ethnic family, which is that one person can have one experience, and then you are surrounded by other people that have gone on to have completely different experiences, all very individualized. I feel like we are interior and exterior people, generally speaking—especially if you come from a larger family, you have your personality that exists within that, and then you have your personality to exist in the wider world. And sometimes they overlap, and sometimes they don’t. For me, that’s such a big part of my life as a Latina woman. My family sort of shrunk by age, because I was raised by my grandparents, and so their siblings were my aunts and uncles and have now passed away, and so I think some of it was also just ghosts. Ghosts, memories—recreating things that I missed in some funny way. It was a way to pay homage to some really great times in my own family.

EE: I’d even extend the idea of family in this book to the larger neighborhood of Sunset Park, to Olga’s sense of where she’s from and the support she can rely on from that community. Can you talk about putting this family and this neighborhood on the page? Was that really fun for you?

XG: Oh my god, that was so fun for me. I grew up with my grandparents. My grandmother was a lunch lady at a public school during the day, my grandfather was the night janitor there, in Sunset Park. We lived on the edge of the neighborhood, and all my kid friends lived there, and so those streets are so ingrained in my memory. It was fun to write, even when it was just Olga walking from the subway to her house. I just felt it so viscerally. I felt like it’s a place that people don’t get to see. And I’ve been kind of pissed. I was getting pissed that Brooklyn is owned by completely different people who have just come in, and have these white collar jobs, and live in these five neighborhoods, and everything’s about interpersonal, contemporary peer drama and I was sort of bored of that and frustrated and I wrote this to reclaim my fucking place. I want to retake it. I’m repatriating it from fucking hipster movie locations. It was important to put my stake in and say, it’s not just that. It’s all of this.

When I first met Alfonso [Gomez-Rejon] about making the Hulu adaptation, we spent half the conversation talking about The Fortress of Solitude [by Jonathan Lethem]. I needed the adaptation to feel the way Fortress made me feel—I felt so seen, in that place. And that’s what I wanted: if you were from Brooklyn, I wanted you to watch this and really feel seen.

I also wanted to write about the weird experience of having a lot of white skin privilege and being cognizant of it. One of the things about Olga is that she feels completely comfortable in her skin. She has a complicated family relationship with their mom; she’s not quite motherless, she’s not quite an orphan. She doesn’t feel quite Puerto Rican because she’s become so bougie, but she doesn’t quite feel that she’s of that WASPy world, either. So the only place where she feels 100% is that she knows she’s from fucking Brooklyn. I think that comfort in your skin about something is so important to establish. And I felt the way to establish it was by showing that love she has, like a bit of a love letter. I also did it somewhat with Fort Greene [where Olga lives]. Because when I moved to Fort Greene, 17 or 18 years ago, it was a mecca for lower-income artists of color. And then the high rises came, and it changed the whole thing. I wanted to show how it feels to see that coming, the sand literally being washed away under your feet.

EE: There’s a wonderful, biting humor in Olga Dies Dreaming. I laughed out loud several times just in the first few pages. But it’s also a book with a lot of struggle and pain in it: Olga’s romantic struggles, her brother Prieto’s political struggles, even Puerto Rico’s struggle to get out from under the boot of US political and economic opportunism. And then Hurricane Maria descends on the island. What can you tell me about the process of balancing those darker elements with the wit and humor that we love from Olga?

XG: That’s such a great question. Once I had Olga, and the world we were going to explore, I knew that the voice would be so important. So before I seriously started writing, I carefully re-read three books. I re-read The Fortress of Solitude, I re-read Gary Shteyngart’s The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, which is one of my favorite debut novels, and I re-read The Sellout by Paul Beatty, which is also one of my favorite novels of all time. I knew that the voice needed to be quite biting, and so ultimately that was a voice decision; I do feel that humor is a voice decision. And when it’s so character driven, like this book is, when the characters go through pain, and you experience that with them, knowing when to shut that humor off becomes really organic. I also think if you’re a person with a fucked-up sense of humor, which I absolutely am, you will find everything slightly funny. Like even when things are kind of tragic. I knew the voice had to have—I don’t want to say snark—but a voice that was willing to expose truth wherever it saw it. The narration is very close to the characters, so I think I’m really saying things the way they see them.

EE: I’d love to know a little bit about the process of writing this book, and then revising it. How quickly did the first draft come together? How different is the final version?

XG: This book came together really quickly. I was obsessive, working on it. I started it in February of 2019 and had a full draft, 400 pages, by Halloween. Half that time, I was working full-time. So from February to July, I’d get up at five, and work on it till seven, and then stumble into work. I was writing in my head on the train. Then the next morning, it was like putting down on paper what had been happening in my head. I stopped doing anything else. And then when I got to Iowa [Writers’ Workshop], it was this beautiful luxury to just write. What a privilege, to just write; it was the most privilegey thing that had ever happened to me. I turned 42 a couple weeks after I got there. The great thing about doing that program when you’re older is that you know that two years goes by like the blink of an eye. So I treated it like that. I was absolutely just that Kermit the Frog typing GIF. I could hardly sleep, I did crazy hours. Sometimes I’d go until one or two a.m. and then wake up and start again at six. It was propulsive.

The biggest change from the first draft, in terms of revision, is Prieto. In the final version, he’s a much fuller character. That change came when I went to Puerto Rico to do revisions in January of 2020. A friend of mine from workshop was so generous to read it again—Alonzo Vereen, I need to name him. He’s read this book three times, from its earliest draft. He wrote a note that was like, “You’re flying too close to the sun, Icarus. You’re doing too much.” But I didn’t want to change it. I didn’t want to make Prieto have fewer problems. But because of that note, I realized that I was cramping his story; he didn’t have enough space to experience it right. So sometimes the note isn’t exactly what you fix, but it gives you insight into what the real problem is. I feel so blessed that I got that note. By the time I got to the end of revisions, Prieto was an amazingly rich character.

EE: You posted on Instagram about your journey from wedding planner to novelist, and how living that life helped you write Olga’s. You said, “Olga is the woman I imagined I’d have become had I never gone to therapy.” I love that. I wonder how many of us novelists that’s true for. Can you talk more about that idea?

XG: I think sometimes we’re doing something, and we feel frustrated by its limitations. Olga’s mother, Blanca, says, “I felt too small in my skin.” Planning weddings can be really fun, and I had a lot of really weird, crazy experiences. Wedding people, event and hospitality people, across the board, are the funnest, coolest people, because we value the person washing the dishes as much as we value the person paying the bill. We know that the bus driver for the shuttle bus is actually the linchpin to the entire night. That gives you a very different perspective on class, and the value of people, and reminds you that we all have stories to tell. It also connects you to a lot of different types of people, in a world where we often get siloed and end up staying around people exactly like us. That was a great thing for me, but I didn’t always feel like that work was using all of my brain, the way that I felt my brain could be used. That energy sometimes turns into more unchanneled energy.

I used to say that about a lot of the intense moms I’d deal with in wedding planning. These intensely smart moms hadn’t worked in three decades. They had master’s degrees but hadn’t done anything with them. And that energy all gets channeled into fucked-up things, and suddenly the color of a rose is the most important thing in the world. And I was seeing that energy in myself. My grandfather had ALS. And I got divorced. And it was a recession. And my ex-husband said, you need to talk to somebody. And I knew he was right. I had all this misplaced energy, and it was turning into stuff that was very competitive, and petty, and I was always looking at what everybody else was doing. That changed for me once I started going to therapy. And then I realized it was very, very deep-rooted, and about a lot of other things. So when I was writing, I thought, what if I hadn’t done that? And who would this 40-year-old woman be, ten years calcified in the same coping mechanisms? Olga is absolutely an avatar for me, but she’s definitely me untherapized. My worst self, my lesser self, but at the same time, Olga is fundamentally so good, a good human being. I found that an intriguing premise.

EE: One of the ways Olga deals with her conflicted feelings about working with wealthy, WASPy families is by gently gouging them in lots of ways, like adding big late fees to their bills. She thinks a lot about money: who owes her what, when she’ll be able to pay vendors, when co-workers or staff might be short on cash. Can you talk about including that in this book?

XG: When I was doing wedding planning, there were moments when very wealthy people would owe us tens of thousands of dollars, and just say “Oh, we’ll send the check next week.” But for us, that payment was due on the second, and I was counting on that money coming in so that the check would clear by the fifteenth, when we’ve got to pay the rent on the office. When you’re dependent on someone for your livelihood, you are living in a fear-based brain space. I wanted to call attention to that fact in a very subtle way, because it’s so fucked up. I wanted to show that this is something lots of working people have to struggle with. I wanted to at least make people stop and think about it. The first time I workshopped this book, someone said, “I don’t remember the last time I read a book that talks about money so openly.” And that was something I was really proud of. I have spent so much time thinking about money. I’ve been poor as a kid, I’ve been poor as an adult. I’ve been more comfortable, and I’ve been quite comfortable. I’ve had many different circumstances. And the way that cortisol works when you don’t have money and you don’t know if you’re eating—like, God bless. Once during the recession, someone loaned me $60 to get basic groceries and get my clothes for work from the dry cleaners. That is a real thing. And I think that’s life. Yiyun Li always says, when she does a craft talk, “How does this person make money? How are they in that house?” That’s a very grounding, real thing that we should all as writers be thinking about more.

People have said to me, “It’s disgusting that your clients spend so much money on one day.” And I don’t think it is. I think it’s amazing. They should enjoy it. It’s a whole economy. What I think is unfortunate is that we live in a society where we don’t have to think about other people. The idea of a high-end Latina wedding planner that has insight into these different worlds just felt like such a great way to break us out of that strata.

EE: In my experience, writing can feel a lot like excavating the history of our own lives, digging into the mess and trying to put a story to it. I think this is true even of writing that is not particularly autobiographical. We put so much of ourselves on the page. Are there parts of this novel that were particularly difficult to write? Parts you’re nervous for the world to see?

XG: There have definitely been various fears along the way, but now my concerns are super personal. The thing about growing up the way that I did, I was an only child, and I lived with my grandparents. In my family, I wasn’t allowed to have feelings about being abandoned by my mother. I was supposed to just be really grateful that I was taken care of, and just buck up and keep going. Some of my family has read the book already, and it’s been interesting for them to see that I did have feelings about it.

But in the public arena, I’m very proud of it as a piece of art. I’m proud of it. I wrote it for Latinos, I wrote it for Latinx people. I wrote it to say, “Look, I see you, and I want to show us in a different way, I want to show this side of our community and our experiences.” I wrote it for Puerto Ricans, and I wrote it for Brooklynites. So at the end of the day, in terms of the public arena, I can feel confident about my intention and what I did.

EE: To me it seems that there’s a theme running through Olga Dies Dreaming, about education and passing down knowledge in families—teaching the younger generation about Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican figures in a way they certainly won’t be taught in school. It struck me as very apt since I think you are probably educating many readers about that history through your book. I certainly include myself in that. Did you feel any pressure with that, knowing that your work might be not just entertainment but education?

XG: I felt the pressure to make sure that if you’re going to talk about something, that it’s right and accurate. But mostly I just get really excited that maybe people will care. When I started writing the book, it was really an homage to my grandfather, and me being pissed off about the fact that we have a fucking colony and nobody gives a shit about it. Working on the Hulu show, I have an assistant who is from San Juan. And there are just rolling blackouts there on a constant basis. The ignorance about it is crazy. To me, it’s a civil rights issue. It’s a voting rights issue. It’s all of these things. If people care about that, even just a little bit, after reading this, then that’s great.

I also think it’s important to have a Latino story that is not just an immigration story. Because where we are, there’s a long legacy of people being Americans and also being Latino. I want people be cognizant of that. It’s exciting.

I think it’s a very American book. If I were to say a theme for this book, I personally believe that you can love imperfect things. And people. I think that’s why you can have ugly characters but they can still be lovable. My point here is that you should be able to say, “we’re colonizers, we still actively exploit a colony.” But that doesn’t mean that I hate America. It was also very important to me that I never make it seem like I know what to do. Only Puerto Ricans know what to do about Puerto Rico, right? My opinion doesn’t matter. I just think we shouldn’t have a colony, and I want to raise some awareness around that. We should all be disgusted by it.

EE: You’ve recently added screenwriter to your bio, working on the Hulu pilot based on your book. I’ve known people who’ve had their projects adapted for the screen, but none who did it themselves! What has it been like making that transition? Is screenwriting more collaborative? Does that make it easier, or more difficult?

XG: It’s definitely more collaborative. It’s made me a better prose writer. Alfonso and I are co-producing, and we made a decision really early on that we weren’t going to use voiceover as a tool for Olga. So you lose interiority. And then suddenly you have to think, what do I learn about her when I look around her apartment? What do I learn when I’m in her closet? How are her dishes kept? It does make you a better prose writer, because there’s all these visual cues that a lot of us leave on the table, or even audio cues.

When there was interest in adapting for film or TV, I remember that people said, “You know, we could get this done faster if you weren’t attached.” And I said, “Well, it’s 10 am. If by six o’clock, you can come back to me with a middle-aged Nuyorican screenwriter, I will consider stepping aside. And otherwise, that’s it.” And in the end, I was so fortunate, because Hulu felt that the world that I built was so specific, that I had to do it. They were placing a lot of confidence in me. With confidence, you also feel pressure, so I am living in a slight space of being stressed out. But Alfonso was the best film school a girl could go to. He’s intensely patient. He suffered through many, many bad first stabs at a script. I watched and read so many pilots, sitting with the scripts, and starting, and pausing. I learned so much that way. But I do still think it is much harder to write a novel, because it requires a commitment to world creation. You don’t get to lean on anything else.

I used to run, and what I loved about it—Murakami writes about this—is that running has almost no barrier to entry as a form of physical fitness. You just have to get sneakers, and then you can go. I think what I love about writing is that you can create insanity, and all you need is a typewriter. Just access to a keyboard. I love that. It can be as pure as you want it to be. Nobody’s going to come in and say, we can’t do that scene. That can’t happen anymore. You don’t have the budget to do this. It’s the beauty of that, and how pure it is that it doesn’t require very much. You could just be an avid reader and turn yourself into a great writer, and that is a beautiful thing.

*

Olga Dies Dreaming is available now from Flatiron Books.