Yesterday, June 20th, marked the official first day of summer! Though the longest day of 2024 has come and gone, the season still promises a plethora of long afternoons and lazy nights. Many of us at The Common cherish this time as an opportunity to comb through our bookshelves and catch up on our neglected To Be Read lists. In this edition of Friday Reads, our editors and contributors share what they’re reading this summer, with recommendations in an array of genres and topics fit for the park, a road trip, a cool refuge from the heat, or whatever other adventures the season may have in store. Keep reading to hear from John Hennessy, Emily Everett, and Matthew Lippman!

All posts tagged: 2024

Museum Ice (Extended Dance Mix)

Anna was slow to do the math. B saw it instantly—what might be left after everything else melted away. White captions flickered in the dim exhibit hall.

B had turned thirteen that fall, ready to join Anna on a trip that was part research, part treat and adventure, the first time they had left the country together, alone. A few days in Rosario (a university lecture, an interview with a playwright), the long bus to Buenos Aires. Invited to contribute to the itinerary, B asked to see glaciers; Anna booked a half-day trek across the ice.

Passengers all around them had clapped when they landed in El Calafate. “That’s so sweet,” B said, joining in. Anna clapped, too, hoping it was thanks, not bald relief. The tiny airport was rapidly navigated. Advertisements lined the baggage claim, placed to catch a teenager’s eye. “They have an ice bar at the ice museum,” B said. “Can we go? There’s a free shuttle from the tourist office.”

Para-

Photo courtesy of author.

Cherokee, NC and Phoenix, AZ

As a child, I watched horror movie after horror movie. An attempt to make myself brave or to make others think I was. And now, I fear I’m manipulative because how much can a person really change. Bones and weight and cartilage can only be altered to certain degrees.

When it comes to film, body horror disturbs me the most. Things that happen to a person’s body without their permission. And sometimes they don’t notice until their bodies are so acted upon that they are grotesque, twisted, so completely othered with pain they are no longer sovereign, but colonized by something outside of themselves.

Nadryw | Feeling Language

By JONË ZHITIA

Translated from the German by LEANNE LOCKWOOD CVETAN

Piece appears below in English and the original German.

Translator’s note:

This essay, presented here in its entirety, won the 2022 Wortmeldung prize awarded by the Crespo Foundation, and, to me, is the thousand words expressed by the picture of the immigrant soul. The submission theme was: “Ships at anchor, cars in parking lots, but I am the one who has no home. How can flight, exile, and homelessness be put into words?”

Return to One’s Roots, Return to a Person, Return to Oneself: Vika Mujumdar Interviews Susana Praver-Pérez

Susana Praver-Pérez’s work, moving fluidly between English and Spanish, from Puerto Rico to California and New York, is a moving meditation on how place shapes our understanding of ourselves and the world. Praver-Pérez’s debut collection Hurricanes, Love Affairs, and Other Disasters, and recent collection, Return Against the Flow, reckon with how we make a place home, considering with care and generosity the landscape of Puerto Rico and its impact on her selfhood. In lyrical, narrative poems, Praver-Pérez examines how geography is defined by its landscape and people. Through the narrativization of lived experience and the intertextual poetry of others, Praver-Pérez’s collection, Return Against the Flow is a necessary documentation of the way language shifts across landscape and time.

In this interview, VIKA MUJUMDAR and SUSANA PRAVER-PÉREZ discuss place and geography, the shifting influences of language, and the transitory nature of diasporic belonging.

Podcast: Mayada Ibrahim on “Symphony of the South”

Mayada Ibrahim speaks to managing editor Emily Everett about her translation of “Symphony of the South,” a short story by Tahir Annour that appears in The Common’s most recent issue, in a portfolio of writing in Arabic from Chad, South Sudan, and Eritrea. Mayada talks about the process of translating this piece, including working with the author and TC Arabic Fiction Editor Hisham Bustani. She also discusses gravitating toward translation as a way to reintegrate Arabic into her life, after years of studying and learning in English. Her translation of Forgive Me, a novel set in Zanzibar and co-translated with her father, will be out in the UK this year.

May 2024 Poetry Feature: Pissed-Off Ars Poetica Sonnet Crown

-

- (Written after the workshop)

Fuck you, if I want to put a bomb in my poem

I’ll put a bomb there, & in the first line.

Granted, I might want a nice reverse neutron bomb

that kills only buildings while sparing our genome

but—unglue the whole status-quo thing,

the canon can-or-can’t do? Fuck yeah, & by

“canon” I mean any rule, whether welded

by time, privilege, or empire, & also by

the newer memes. Anyway, I want the omelet

because of the broken eggs. I want to break glass

into dust, to spindrift it into new form. I want

to melt mortar down into quicklime that burns.

Less piety, please. Any real response to my poem

will do—laugh, cry, yawn—or STFU & go home.

From Sieve: A Preliminary Draft and a Ruin

Catalonia

The sea has moved inland. Below the rectory on the hill, the fields and villages under the fog. In the first blue of the morning. The bell tower of the church in Lladó surfaces through it. It is a few minutes away by car. In Lladó the fog hangs in the streets, close to the ground. Each building in isolation within it. The old church, the locked doors: wood doors open onto metal doors that are molting their skin. The keyhole the size of an eye.

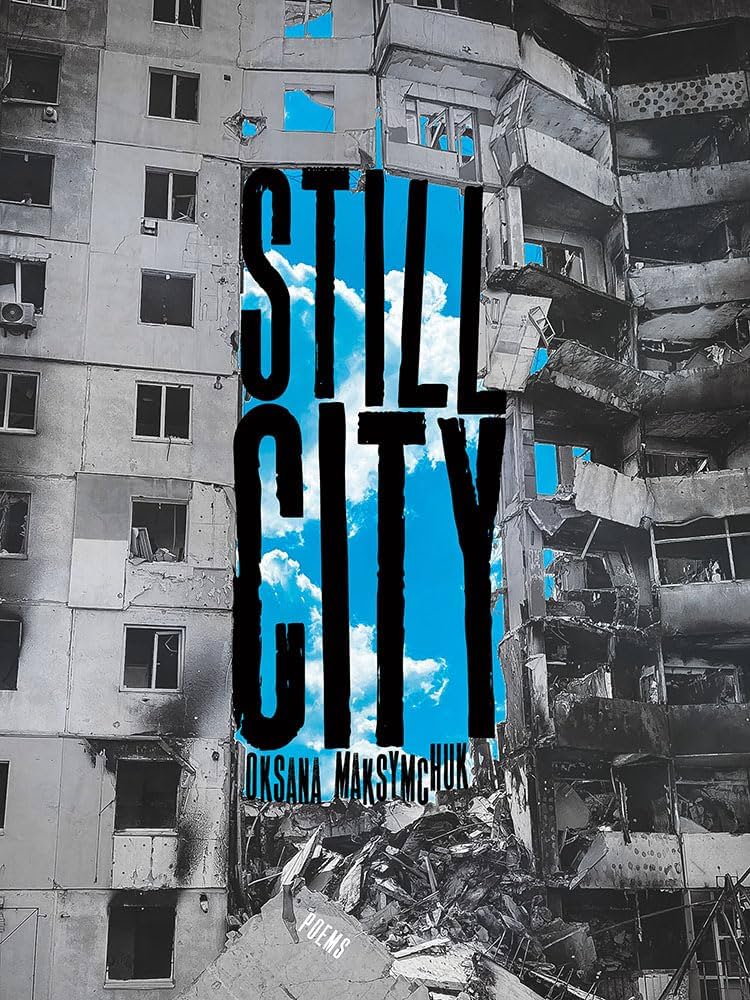

Review: The Extinction of Irena Rey

By JENNIFER CROFT

Review by CHRIS JOHN POOLE

At first, the autobiographical roots of The Extinction of Irena Rey seem simple to trace. This is a novel by writer-translator Jennifer Croft, who works in Spanish and Polish; its protagonist is a Spanish writer-translator. This is a novel from the acclaimed translator of Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights; the eponymous Irena Rey is a Polish literary megastar. This is a novel from a staunch advocate for translators’ visibility; its eight main characters are all translators who seek—and perhaps supplant–their elusive muse.

Yet it is the very abundance of extratextual parallels that makes it so difficult to situate Croft within her text. Unlike Croft’s debut Homesick, a hybrid novel-memoir, The Extinction of Irena Rey provides no single stand-in for its author; instead, a network of interlinked characters echo Croft’s own life. From the novel’s tantalising biographical parallels, countless questions arise: is Irena Rey modelled on Tokarczuk or Croft? Is protagonist Emilia a self-insert, or a novel creation? Ultimately, it seems, these characters are hybridisations of Croft and her influences, as within this novel the lines between self and other, like those between truth and fiction, begin to blur.

Losing the Daphne

It was neither ice nor heat. That is, not one single ice storm and not one single heat wave. The relentless strangeness of weather left the Daphne this way, budded around the edge but dead in the center. She will probably not last another hot summer.

Daphne is a Daphne odora “Marginata.” The cultivar “Marginata” indicates glossy leaves that sport a pale, bright edge. It was the odora though—the sweet, pink mid-winter scent reminiscent of Fruit Loops—that made us want her in the first place, and tend to her, and carry her with us from one house to another, that made us prop her up when she grew heavy and underplant her with special varieties of bleeding heart and black mondo grass that would best show her off, that made us love and root for her, over and over.