In this month’s poetry feature, ZACK STRAIT talks with RICHARD SIKEN about influences, confrontation, readers, accountability, sacrifice, balance, surface beauty, deep meaning, writing, and Waffle House.

All posts tagged: 2024

December 2024 Poetry Feature #2: New Work from our Contributors

New work by LEAH FLAX BARBER, ROBERT CORDING, PETER FILKINS

Table of Contents:

- Robert Cording, “In Beaufort”

- Leah Flax Barber, “School Poem” and “Cordelia’s No”

- Peter Filkins, “Trains”

In Beaufort

By Robert Cording

At a rented air B&B, I am sitting on a swing

placed here just for me it seems,

or just to carry off my worries and sorrows

as I rock slowly, back and forth, taking in

the shifting colors of the Broad River that circles

this marsh pocketed with cut-outs of water

and long inlets that circle round and round

as if it were one of those spiritual labyrinths

that bring calm as the center is reached.

The Most-Read Pieces of 2024

Before we close out another busy year of publishing, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on the unique, resonant, and transporting pieces that made 2024 memorable. The Common published over 175 stories, essays, poems, interviews, and features online and in print in 2024. Below, you can browse a list of the ten most-read pieces of 2024 to get a taste of what left an impact on readers.

*

January 2024 Poetry Feature: Part I, with work by Adrienne Su, Eleanor Stanford, Kwame Opoku-Duku, and William Fargason

“I wrote this poem on Holy Saturday, which historically is the day after Jesus was crucified, and the day before he was resurrected. That Spring, I was barely out of a nervous breakdown in which I had intense suicidal ideation … The moments of quiet during a time like that take on more meaning somehow, reminders I was still alive. And that day, that Saturday, I saw a bee.”

—William Fargason on “Holy Saturday”

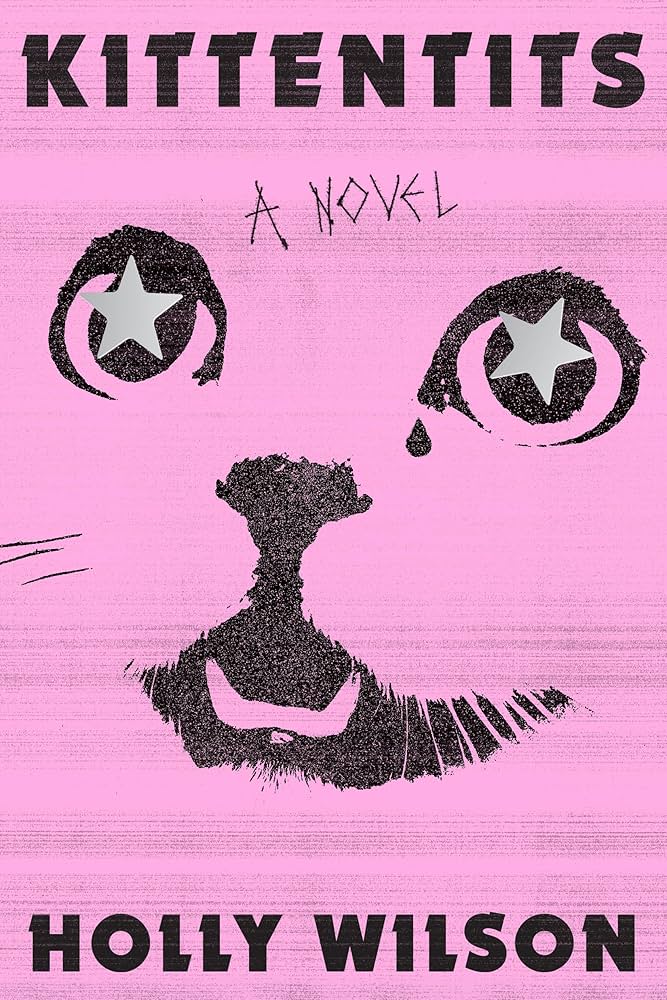

Review: Kittentits

By HOLLY WILSON

Reviewed by OLGA ZILBERBOURG

Molly is a badass. Obvious, isn’t it, from the novel’s title? Kittentits. That’s her, Molly. She’s a motherless white ten-year-old kid, living in Calumet City, Michigan. It’s 1992, and she’s obsessed with attending the Chicago World’s Fair, about to open downtown.

Before she gets there, Molly comes to idolize a woman who tried to kill her conjoined twin; runs away from home to Chicago’s South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville; meets an elderly polio patient living inside an iron lung who gives séances; and befriends an African-American ghost boy and artist, Demarcus. Together, Molly and Demarcus hatch a plan of necromancy to commune with the ghosts of their dead mothers. They camp out at the Fair for weeks, waiting for New Year’s Eve to perform the ritual.

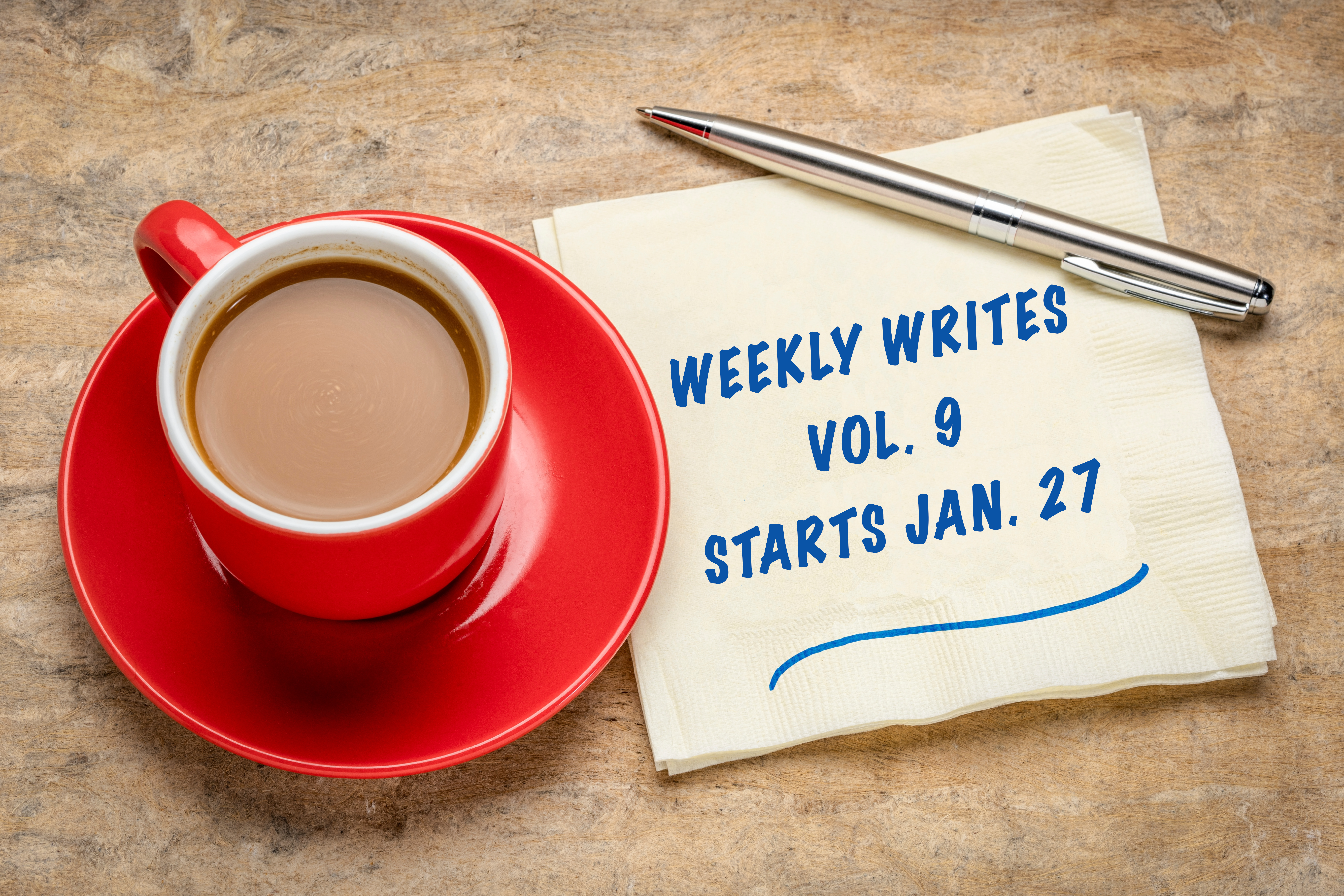

Weekly Writes Volume 9 is here to keep you accountable!

Weekly Writes Vol. 9 signups have closed. To hear about our next round of Weekly Writes when it opens, please register your interest here.

Is your New Year’s resolution to write more?

To write beyond your comfort zone?

To stay accountable to your goals and projects, every week?

The Common is here to help!

Weekly Writes is a ten-week program designed to help you create original place-based writing and stay on track with your goals in the new year, beginning January 27.

We’re offering both poetry AND prose, in two separate programs. What do you want to prioritize in 2025? Pick the program, sharpen your pencils, and get ready for a weekly dose of writing inspiration (and accountability) in your inbox!

Holiday Reads 2024

What We’re Reading: December 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

If you’re in need of a deep breath amid the holiday frenzy, look no further. This month, Issue 28 poets and longtime TC contributors OLENA JENNINGS and ELIZABETH HAZEN bring you three recommendations that force you to slow down and observe. Hazen’s picks provide an intimate window into the paradoxical, tragic, and sometimes ridiculous characters that inhabit our world, while Jennings’ holds up a mirror to readers, asking them to meditate on the act of viewing itself.

|

|

Chantal V. Johnson’s Post-Traumatic and Kate Greathead’s The Book of George; recommended by Issue 28 Contributor Elizabeth Hazen

Typically, I have a few books going at once, and I am almost always at the very least reading one physical book and listening to another. Often, the pairings reveal interesting connections, and my most recent reads—Kate Greathead’s latest, The Book of George, and Chantal V. Johnson’s debut, Post-Traumatic—did not disappoint.

Both books are contemporary, the former out just this October, the latter in 2022, and feature protagonists who are deeply flawed but trying to figure out who they are. They hail from starkly different backgrounds, though, and this determines the starkly different difficulties they encounter as they navigate adulthood.

December 2024 Poetry Feature #1: New Work from our Contributors

Works by JEN JABAILY-BLACKBURN and DIANA KEREN LEE

Table of Contents:

- Jen Jabaily-Blackburn: “Archeological, Atlantic” and “Velvel”

- Diana Keren Lee: “Living Together” and “Living Alone”

Archaeological, Atlantic

By Jen Jabaily-Blackburn

A morsel of conventional wisdom: Never use the word

boring in a poem because then they

can call your poem boring. The boring sponge can’t

do everything, but can make holes in oysters, & for the boring sponge, it’s

enough. I miss boring things like gathering mussel shells

for no one. I miss being so bored that time felt physical, an un-

governable cat sleeping over my heart. I have, I’m told, an archaeologist’s

heart. I have, I’m told, an archaeologist’s soul. An archaeologist’s eye, so

The Laws of Time and Physics

Rome, Italy

I am tangled up in time. My body is the fine silver of my necklace, tying knots through curls of hair. I am the feeling of trying to untangle its spindled chain with too thick fingers, tips all pink, reaching for a dexterity they just don’t have. I’m caught up like that. Strangled.

Churning Up Mystery: A Conversation between Theresa Monteiro and Abbie Kiefer

THERESA MONTEIRO and ABBIE KIEFER are poets with recently published debut collections. Monteiro’s Under This Roof examines the magnitude of human experience through the details of the ordinary. Kiefer’s Certain Shelter addresses the death of a parent, a Maine mill town’s long fade, and the search for refuge in a faltering world. Both books are deeply rooted in domestic spaces. In this conversational interview, the poets and friends discuss the challenges of writing about quotidian places in surprising ways and how they use the specific and personal to comment on universal themes: loss, empathy, connection, and mystery.