By JENNIFER ACKER

Mostly, Les gossips and writes about girls. One’s “a real peach” and another “darn nice.” Poor Esther has legs like parentheses—she “must have been born with a barrel between her legs.” Then there’s Mildred, who’s darn good-looking but too biting: “Sarcastic is no word. That’s complimenting her.” Les gets a little revenge when he sees her at a dance with “an awful dopey looking hobo.” He has a good time, even though “nearly every girl there was a pot.”

Mostly, Les gossips and writes about girls. One’s “a real peach” and another “darn nice.” Poor Esther has legs like parentheses—she “must have been born with a barrel between her legs.” Then there’s Mildred, who’s darn good-looking but too biting: “Sarcastic is no word. That’s complimenting her.” Les gets a little revenge when he sees her at a dance with “an awful dopey looking hobo.” He has a good time, even though “nearly every girl there was a pot.”

I have to assume that Malvin, when he answers, writes the same. But I don’t know, because those letters have been lost, dispersed. I’m reading what Malvin received and chose to keep.

I’m trying to build a picture of Malvin from the words of others, bits and pieces. And I find surprises from the beginning: Dear Mally. My grandfather was Mal to everyone who did not call him Grandpa or Dad. But Les and Lionel and the others call him Mally. Except for Eleanor. Eleanor who would become my grandmother, and who was known as Ellie. Ellie & Mal. But Les writes to Eleanor and Mally.

Les’s letters are easy to read, written in a clear, sometimes elegant cursive, sometimes in green ink. He has his own stationery stamped with his Brookline address. Occasionally he pens notes on the letterhead of Boston Edison, where he works in advertising. As the years go by, Les’s burden of relaying hometown news increases. After Malvin’s postgrad year at Andover and four years at “Tech” (MIT), he never settles permanently back in Boston. From 1937, Malvin is in New York. Les’s letters are filled with queries about when his friend is coming home for a visit. Les wants to go to “NY,” but he usually can’t afford it. As I sit reading these letters that span the crucible of adolescence to adulthood, it occurs to me that just as I am trying to understand Malvin from the slightest cues, his friends also had a hard time pinning him down. Les is shocked when Mally posts a quick reply. Lionel complains that his friend’s letters are too short and poorly typed.

I also realize that these letters once lived in the space above my head. In the crawl space above what used to be the clothes closet in my grandparents’ bedroom in this cabin on Washington Pond. When the cabin was renovated, after my grandparents’ deaths, the closet was converted into a bare nook outside the new master bedroom. It’s furnished with a small writing desk and a chair borrowed from the dining set. There’s a window ahead that peers into the woods and another on the right that faces the lake but is too high to view the water. Behind me, my grandmother’s low vanity chair with wicker seat lies abandoned along a wall. Here, tucked along the roofline, is where Malvin stored the letters no one knew about. Did he hide them or simply forget they were there?

Without Malvin’s letters, without his words, I have only limited glimpses into his personality—his motives and desires. Around that undefined core, what accumulates instead are details of his world. The world of these boys becoming men. They are working-class, sons of small business owners, the first of their families to attend college. Familiar with, but not from, a big Eastern city, they go to public school and share cars, changing the oil and tires and waxing the surface “until it shines like chrome.” They are vibrantly social, hosting and attending dances, enjoying weekends filled with football games, drives into the country, swimming, bridge nights, theater and concerts and sometimes museums. They carefully parcel their money to take girls out, complaining when the food is pricey and the shows are “punk.” They are often broke. The letters refer to funds borrowed, pooled, anticipated, and repaid, down to the cent. In the early years, Malvin and Lionel and Les bank together in a Christmas Club, a savings program initiated during the Depression.

Without Malvin’s letters, without his words, I have only limited glimpses into his personality—his motives and desires. Around that undefined core, what accumulates instead are details of his world. The world of these boys becoming men. They are working-class, sons of small business owners, the first of their families to attend college. Familiar with, but not from, a big Eastern city, they go to public school and share cars, changing the oil and tires and waxing the surface “until it shines like chrome.” They are vibrantly social, hosting and attending dances, enjoying weekends filled with football games, drives into the country, swimming, bridge nights, theater and concerts and sometimes museums. They carefully parcel their money to take girls out, complaining when the food is pricey and the shows are “punk.” They are often broke. The letters refer to funds borrowed, pooled, anticipated, and repaid, down to the cent. In the early years, Malvin and Lionel and Les bank together in a Christmas Club, a savings program initiated during the Depression.

They are Jewish, confirmed in the temple, but they are scarcely observant. Les goes to Kol Nidre and daytime Yom Kippur services and asks Malvin, “Are you fasting? I guess I will last the rest of the day.”

They are Jewish, confirmed in the temple, but they are scarcely observant. Les goes to Kol Nidre and daytime Yom Kippur services and asks Malvin, “Are you fasting? I guess I will last the rest of the day.”

Theirs is a Jewish world—their dates and friends, fraternities and job opportunities—but Jewishness is more a fact of who they are then a guide to what to believe. Lionel, at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, is attuned to divisions and slights. He writes about one social, “We had a fair time, considering we were the only Jews there with all those uncircumcised rats.” When Malvin faces his fraternity options at Tech, Lionel prods: “Tell me about your rushing. What other houses have you been to, and have any bid, and do you think they know you’re Jewish?” Later, apartment hunting near Detroit, Lionel notes, “All the nicer places are restricted if you know what I mean—no Jews or dogs allowed.”

When Malvin is married, Les is asked to be best man and wonders if he needs a hat for the ceremony. Malvin’s answer is lost, but not Les’s next letter:

At first I didn’t get yarmike [sic] as such, but fortunately I have a Jewish brother and he translated it for me. Even though you’re going to have a goi-ish wedding, I think I’ll get me a straw to protect my thinning hair from the midday sun.

I began reading to learn more about Malvin, but I’ve become entranced by Les and Lionel—their humor, their ease, their exploits, their language. How so many of their phrases are both new and quaintly familiar. Girls are peaches; good times are swell. Times, too, are hard; business is sluggish and jobs are scarce. Then comes the war, which Malvin spends in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, while the Army deploys Les to Europe. But I don’t know much about this yet; I’m stuck in the thirties, the growing-up years, which ended when my grandparents married in 1939.

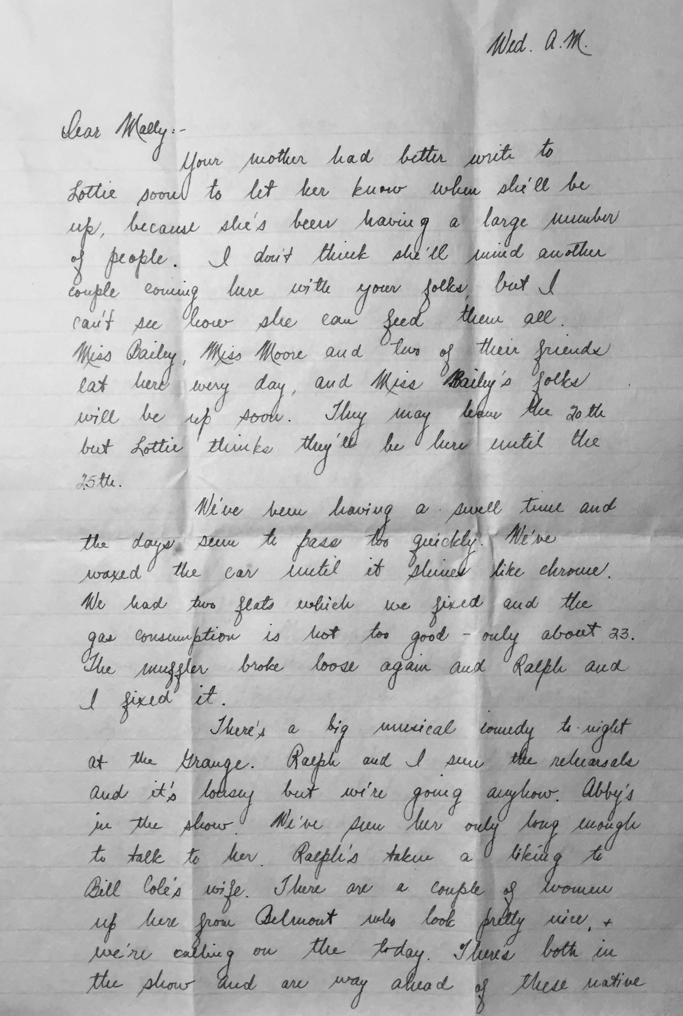

For a while I read along in a timeless fog, unaware of myself, my back against this scratchy chair, the lapping lake outside the window, the eagle that might be flying overhead. Then I read a letter dated only “Wed. am.” Les writes, “Your mother had better write to Lottie soon to let her know when she’ll be up, because she’s been having a large number of people.” Lottie… I should know that name. I have heard it here, in this place, within the past few days. I realize he’s talking about Lottie Prescott, wife of Will. The couple owned a boarding house a couple miles away from here, a farm at the far end of the lake. Lottie managed the boarders, and Will hired himself out as a day laborer, jack-of-all-trades, for a dollar per day. The dirt stretch that connects the paved main road to the cabin driveway is Prescott Road. There’s a picture of my mother as a toddler on Will’s lap. They sit in sunshine in front of the farmhouse’s water pump. She is a fat-cheeked, ebullient girl, and Will is angular, showing just a hint of a smile.

For a while I read along in a timeless fog, unaware of myself, my back against this scratchy chair, the lapping lake outside the window, the eagle that might be flying overhead. Then I read a letter dated only “Wed. am.” Les writes, “Your mother had better write to Lottie soon to let her know when she’ll be up, because she’s been having a large number of people.” Lottie… I should know that name. I have heard it here, in this place, within the past few days. I realize he’s talking about Lottie Prescott, wife of Will. The couple owned a boarding house a couple miles away from here, a farm at the far end of the lake. Lottie managed the boarders, and Will hired himself out as a day laborer, jack-of-all-trades, for a dollar per day. The dirt stretch that connects the paved main road to the cabin driveway is Prescott Road. There’s a picture of my mother as a toddler on Will’s lap. They sit in sunshine in front of the farmhouse’s water pump. She is a fat-cheeked, ebullient girl, and Will is angular, showing just a hint of a smile.

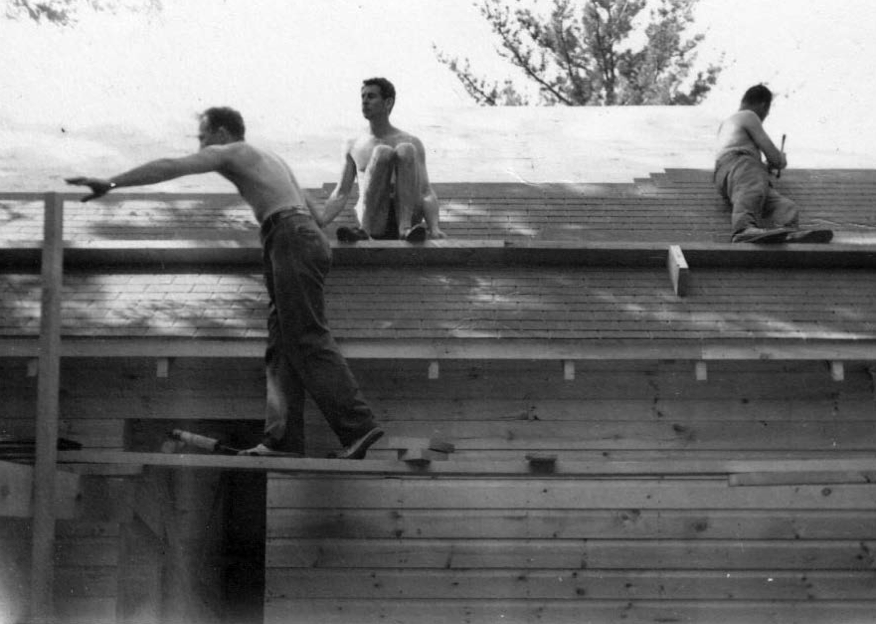

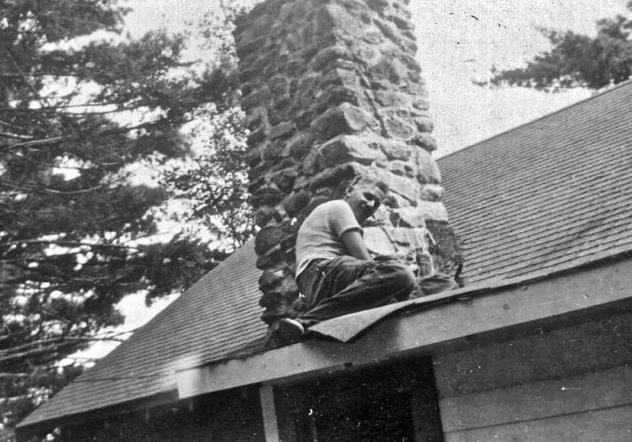

Will was paid to help build the original cabin in 1940. It is, I think, his team of oxen in the photographs, hauling lumber and massive stones. Malvin is pictured perching on the roof next to the fieldstone chimney and, in another photo, hoisting crossbeams in a polo shirt and wide-hipped trousers. There’s a group shot taken in a sunny field, a farmhouse in the background, in which Will’s grim, thin-lipped Yankee face peers from the back row, everyone now in suits and ties. Lottie wears a dark fedora that shades her face and a long-sleeved dark dress. My grandmother is in bright white shirtsleeves and a blue skirt. She must be pregnant with my Aunt Sylvia, but you can’t tell.

Will was paid to help build the original cabin in 1940. It is, I think, his team of oxen in the photographs, hauling lumber and massive stones. Malvin is pictured perching on the roof next to the fieldstone chimney and, in another photo, hoisting crossbeams in a polo shirt and wide-hipped trousers. There’s a group shot taken in a sunny field, a farmhouse in the background, in which Will’s grim, thin-lipped Yankee face peers from the back row, everyone now in suits and ties. Lottie wears a dark fedora that shades her face and a long-sleeved dark dress. My grandmother is in bright white shirtsleeves and a blue skirt. She must be pregnant with my Aunt Sylvia, but you can’t tell.

The picture is captioned The Builders. I’ve looked at it before, for years, and every day for the past week, but only now do I see Les. He’s next to Lottie and Will, in a gray suit and striped maroon tie, almost smiling, high forehead topped by thinning hair (no straw hat). And here is his letter detailing his plans to come up and pitch in:

I have arranged my vacation for the first two weeks in July and would enjoy going to Washington with you…. Who else is going? If you’re all couples how about my getting a girl—if possible. Does Lottie have enough room for such a mob? What are your building plans? What about wood? Can I do any preliminary work for you?

I had never noticed Les in the picture because I never knew him. Lionel and his wife visited over the years and continued to be a part of my grandparents’ lives. My mother is still friends with Lionel’s daughter. What happened to Les? His letters continue through the eighties, and my mother knew his name, but she doesn’t remember him coming to the cabin. This is strange, because Les was there from the beginning. From before the beginning. That letter urging Malvin’s mother, my great-grandmother, to tell Lottie her plans was written years, maybe a decade, before the cabin was built. Les was up at Prescott’s when Malvin wasn’t there; he had his own relationship to this place. Was it Les who introduced Malvin to the pond, the town, the state that became a cornerstone of my grandfather’s life, and because of this, my mother’s home, then mine?

Maybe the letters will unravel this; maybe they won’t. I don’t know yet. I’m just at the beginning of the correspondence, the legal documents and receipts, the pile of papers Malvin left behind. I know only that a strong presence of a man I never knew has been with me here the whole time, as I read his letters to a man we both loved.

Les standardly signs off with That’s about all there is. But I, the unanticipated reader, having reached only 1940, can’t stop. I have decades more to go.

—Jennifer Acker, Editor in Chief

Washington, Maine