SARETTA MORGAN interviews RACHEL ELIZA GRIFFITHS

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a poet and visual artist. Her most recent collection of poetry, Lighting the Shadow (Four Way Books), was published in April. Griffiths teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College and the Institute of American Indian Arts, and lives in Brooklyn, NY. Saretta Morgan corresponded with Griffiths via email over the course of four weeks this summer, during which time they each traversed several locales—Upstate New York, Mexico, Colorado, Vermont and Washington, D.C.—as they discussed form, representation, and the risks of opening oneself up artistically.

Saretta Morgan (SM): Your fourth book of poems came out this year, and you’re very close to completing your first book of photographs and your first novel. You also work in photography and video. Could you share a little bit about your relationship to these modalities? What complications and limitations do you find in each?

Rachel Eliza Griffiths (REG): I like the fluidity each genre offers me spatially, emotionally, and creatively. I can take an idea, word/fragment, or image and open it up across forms. My experiments with video are very recent. I see those efforts as attempts to challenge myself with my photographs and with my writing. I really want to do so much with film. It’s terrifying and fulfilling, which means I’m going directly towards it.

For example, Lighting the Shadow is a verbal, cognitive articulation of an imagination and psyche that I usually nurture through photography. It’s very difficult for me to theorize about my visual work. Because what I’m after [is] the risk and audacity of being fully and imperfectly human.

In terms of limitations, I don’t necessarily think of my process in that way. I’m actively revising, erasing, and leaping between words and pictures. There are endless conversations and experiments! All of these spaces are instruments for something that is intelligent, yes, but always primal. I’m drawn by the mystery, the alchemy, the synthesis. I love questions! It’s up to me to know, to fail, and to get near the original desire I set out to express.

SM: I like that your focus on forms collectively presents an abundance of possibility, and I’m interested in how this abundance relates to your concerns around “the risk and audacity of being human.” The idea of being human is something I find myself wary of, because historically, and still today, as a category, it has been established through limitations, and even presented as a right which one must fight their way into, often by demonstrating an ability to practice acceptable civil, religious, and sexual behaviors. But your ideal of the human seems to require that we fail at sociality. That we be more than/other than/in excess of what society asks of us.

This feels very important right now. On a daily basis it becomes more apparent to all of us that the social conditions we operate within are incapable of (or ambivalent about?) positively addressing the complexity of black and brown lives and living. Do you have any thoughts on this?

REG: I wonder what our greater society might look like if individuals and institutions were able to grasp and to concede to their imperfections—not merely as a means of defeat or justification of prejudice. I think some of the admission is about listening and the subsequent alignment of listening and action. The risk of actually hearing and seeing the Others for the first time. I don’t think that has really happened yet but maybe it will.

The larger world is losing out on the power, innovation, imagination, beauty, citizenship, and compassion of black peoples. When all of that is freely moving and functioning in the world (it has always been moving and present), and is not a charged space of imprisonment or commodity, then we will begin to see a shift. The exchange has always been unbalanced and forced. Even and especially when it comes to rights. The recent language of Black Lives Matter and the immediate revision to All Lives Matter seems to hold some reflection of what we’re speaking of. For black and brown bodies there is a consumptive revision, systemic erasure, hyper fixation (both silent and spoken), and an unrelenting wheel of trauma that must be confronted at any given moment.

There’s a charge for me—as a poet and a photographer—to witness. To leave some vestige of this time through my own (in)sight and my physical presence. There’s a certain self-consciousness that must be penetrated and appreciated rather than discarded or buried.

SM: Your poem “New World” seems to be thinking about the history of encounters between Western culture and other complex and abundant forms of living. Can you talk more about this?

REG: In “New World” I have a line “Walking around in my head, I’m being/watched by my own watchdogs.” This articulation stunned me. It surfaced and made me sit down for a few weeks. I really had to reflect. I thought about whose voices were policing my thoughts and experiences. Not just externally but internally. Not just from strangers but also from family. The poem is about distance, narratives, and authorship. In the poem an unspecific narrator is able to hold past, present, and future in a single glance. The witness is both separated and (dis)connected, indivisible from the narrative. And too often, for me, that is what my experience feels like in this country.

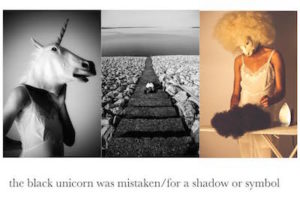

SM: A lot of your photographic work engages the black female body and explores ways to complicate the viewer’s relationship to this subject. The troubling of subject-object relationships seems to help you step outside of—or work without regard to—the residue of the “white male gaze.” That’s my assumption, but is there more to it?

REG: I’m more engaged by circular, non-linear gazes that keep both subject and object in a firm, complicit tension. The tension, for me, is not strictly tied to the white gaze. In fact, it rarely is. I’m interested in the tension amongst bodies of color, women, and what happens to me when I witness myself as both seer and seen. It is even more terrifying to allow an audience to look because I have no control.

There is my fear, my desire, and vulnerability in trying to articulate both the surface and its interior of my own female black body. My physical body, thankfully, connects me to a legacy of strong beauty, power, love, and imagination. In some of the work I feel as though I’m translating or transcribing fragments of cultural or historical narrative. I hope for a conversation, even if it doesn’t occur directly with me. The black female body isn’t monolithic. I understand and fully celebrate our nuances.

Often as I work I am visited and haunted by a diaspora of memory. My entire body is a camera, an aperture. It is similar to the sensation I experience when a lyric insists upon its own visibility and music on the page.

There are so many poets, writers, artists, and creatives who did (and are doing) the work before I entered the conversation. I can’t stop thanking them enough.

What excites me is what’s happening in the work—on the page, on camera, on the stage, in music and in film—about the black female body and narrative. We’re all speaking. We’re all saying See Us. We’re all saying We See Us. And we’re getting reminders from our elders and from the newly born too. We Have Always Seen Us andWe Will See Us In Spite Of…

SM: That “we” is very important. I feel the resistance to unidirectional subjectivity in your photographs through the donning of masks—that obscure identity—and the use of printed signs, through which the people in your photographs speak back directly to the viewer and create a very specific context for the photo at hand. I also see your tendency to place yourself as both subject and object. I wonder whether, and how, you bring these same concerns into your poetic practice? What are the terms under which you understand yourself to act as a subject?

REG: My imagery is not passive. My body, by extension, is not a passive vessel. It would be great to have those who look at images of me in my work look with me and not merely at me. But I can’t control how or where the gaze enters the imagery, which in a sense, is also me. It’s a similar journey on the page. I try to create a vocabulary of photographs or language that is open and charged at once.

Like my writing, [in my photography] I question authorship, invert ownership, and subvert the lineage of American desires, which often veil extraordinary violence. I hope my photographs mostly refrain from subjective judgment but it really depends on the content of the image. In some of my work, it’s about recurrence, call and response.

As you mentioned, I use signs, masks, and texts. I have private and public relationships to all of those spaces. And there are borders where things blur and are not as divided as I might like. A few years ago around the time my paternal grandmother died I began to aggressively incorporate my physical self in my work. I wanted to push against my visual notions of mortality, age, and the relationship of women’s bodies [to] death, language, and art. In my earlier work, I had explored using my body in a very tentative way. I was hiding. But finally I couldn’t ask models to do what I was terrified to do.

Since my mother’s death last summer I’ve been stunned when I cross a mirror and experience her. There is something astonishing about that. So I think I approach the relationship [between subject and object] with discovery, understanding that I have many roles, many faces, and all of them are true, at least, to me alone.

SM: I keep thinking about risk, and the risk of seeing. I think that we can agree very generally on what the risks are for those in society who are not black, and who maintain power through determining what is and is not seen. It’s no surprise that they don’t want to see black bodies, and black women’s bodies, and will go to great lengths and great harm to avoid seeing.

But as you say, we police ourselves in ways that inhibit the power, beauty, and imagination of black living. Sometimes I think about what I’d have to give up to embrace the power of black living fully. Could you share about specific ways you’ve learned to write past some of the watchdogs, which could be thought of as representing your fear of your own power. And what do you risk when you do so?

REG: This is an excellent question for which I can say nothing permanent. When I risk acceptance of self I risk the deep possibility of letting go of so many fears and distractions. No more bullshit.

Earlier, I mentioned my mother’s death, which had always been my greatest fear. Much more so than my own death. Experiencing death with her, in a sense, has made me both skinless and very powerful. I’ve had to let go of destructive ways. I’ve had to do better—not for anyone else, because I have a tendency to place others before myself—but for me. If I’m able to give myself even a fraction of the love and trust my mother gave me, I will survive anything. Alongside my grief a magnificent sense of power, which also includes my vulnerability, has rooted itself. It makes me trust myself to be as complex as I am. It makes me withdraw from spaces and people who want me to be a woman I don’t and can’t know or be. My sorrow is as full and immeasurable as my sense of wonder and gratitude. By risking sight, I can be opened, possessed and obsessed by insisting upon a total and full humanity for myself.

*

Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s most recent collection of poetry is Lighting the Shadow.

Saretta Morgan is an MFA candidate at Pratt Institute. She lives in Brooklyn.

All images by Rachel Eliza Griffiths.