LINDSAY STERN interviews TERESA VILLEGAS

The Common contributor Teresa Villegas and intern Lindsay Stern discuss Villegas’ recent projects, her choice of medium, and the influence of place and the environment on her work. Released in October, Issue 02 features a selection from “El mundo al revés/The World Upside Down,” a suite of 10 prints by Villegas alongside bilingual folktales by Ilan Stavans.

LS: What inspired “El Mundo al Réves”?

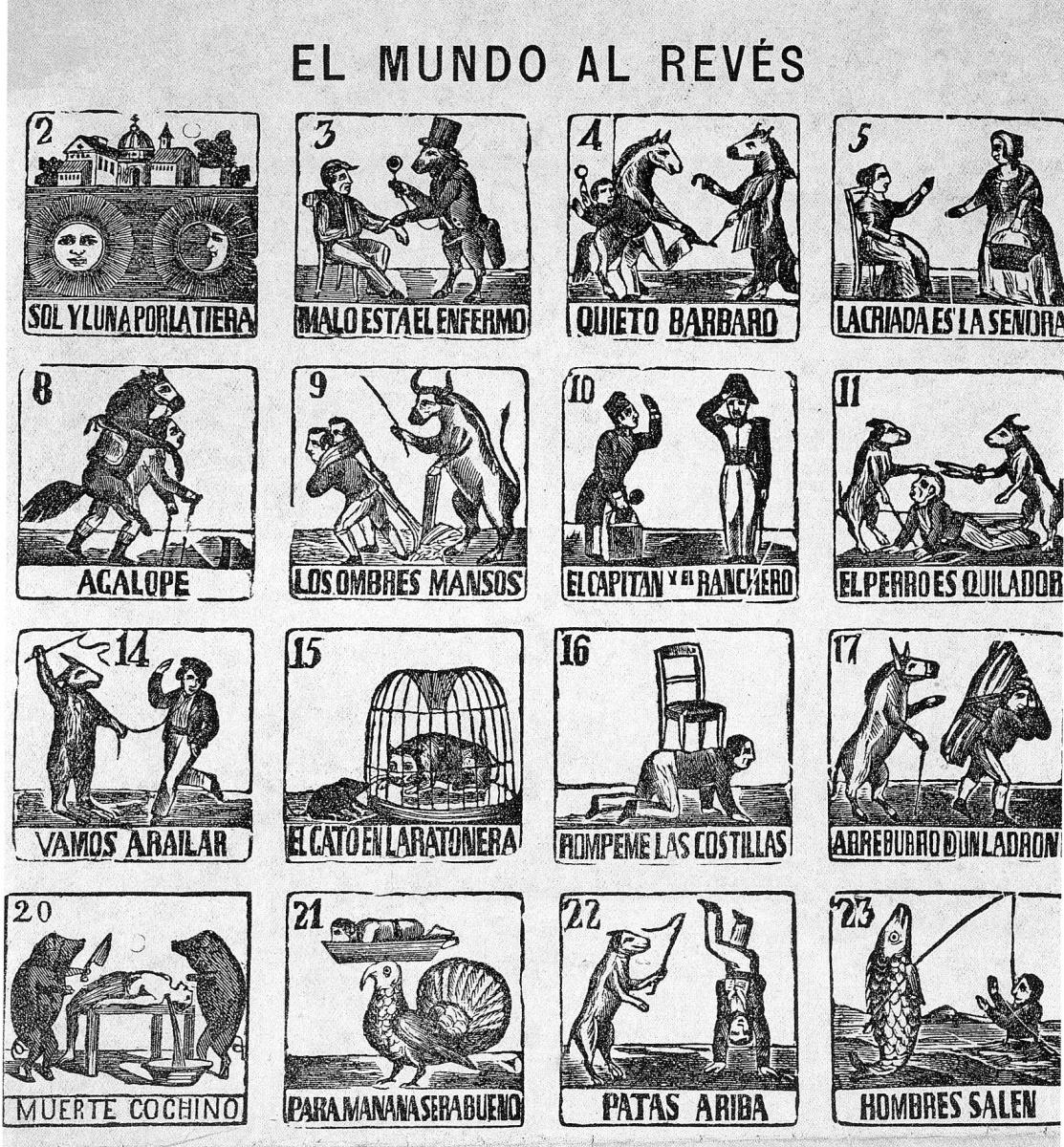

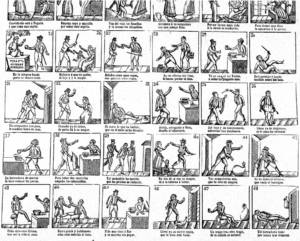

TV: This project began as a question, as most everything that catches my eye. While traveling through Spain 10 years ago, while in Madrid, I came across an old local print shop that sold antique prints, hundreds upon hundreds of stacks of old anatomical relief prints and etchings, lithographs of religious prints, etc., and I came across a black and white relief print, a broadside titled “El Mundo Al Reves” (“The World Upside Down”) that depicted approximately 24 different little scenes of interactions between animals and humans. Except, just as the title suggests, the roles were reversed. The hunting dog was the one holding the gun, while the human ran ahead to retrieve the falling duck from the sky. Or the woman, carrying a horse on her back, as the horse held a whip to her hindquarters. These vignettes also included a few words of text below the image for description for the scene such as “El Perro Cazador” (“The Hunting Dog”).

These simple folk-art illustrations were new to me, and I was so intrigued by their irony and historical value that it inspired me to buy the print and to inquire and learn as much as I could about it. The more questions I asked, the fewer the answers I found. Eventually I did find that the San Antonio Museum of Art had a few of these prints in its collection. It turns out that there were many different kinds of “social code of conduct” broadsides printed, providing a look into the times of the late 19th century Spain. Some broadsides depicted celebrations of carnival, and another titled “Vida de la Mujuer y Hombre Borrachos” (“Life of the Drunk Man and Woman”). Others taught the lives of saints. Most broadsides were placed in public areas to reinforce the community’s sense of right and wrong.

The invention of the printing press enabled advertising and social persuasion in a visual context; it was this early form that interested me. I had decided that I wanted to create my own version, and when the time was right it came to fruition. And I was fortunate enough to have Ilan Stavans collaborate with me to give the project another layer of depth, story-literature and interest.

LS: What inspired your current project? Specifically, your drawings of the Sonoran plants?

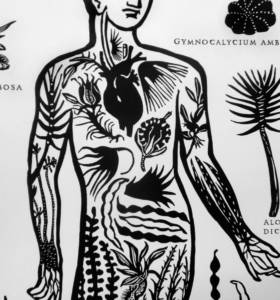

TV: The relief print you are referring to is titled, “Arid Adaptations.” This project was inspired by two causes. First, as a technical endeavor to produce a large size relief print, as I have never carved a relief block this size (60″ x 32″ image on 66″ x 36″ paper). So the physical challenge and the final printing of a piece this size were exciting to me. I worked with Master Printer Brent Bond of Santo Press to guide me through the whole process, which I could not have done without his expertise. I’m working on a mate to this piece using the female body.

And the second, was to create a whole body of work, based on a theme that I have been thinking about for some time now. I am developing a visual mythology of the human body as it relates to the surrounding environment. In “Arid Adaptations,” I have placed the desert plants as internal organs of the human body to emphasize our relationship to the land. I live in Arizona surrounded by the Sonoran Desert, thus the Sonoran plants. I have about five more large figurative pieces I am planning to carve and print that will make up this body of work.

The deeper, bigger, underlying message is for us to become more aware of ourselves in our surrounding natural environments and how we relate to them. This theme began when I started the dialog in my head, “When did man think that it was all right to take and use the Earth’s resources without any regard for the Earth?” I take climate change seriously, and am thinking about how I personally can make changes to adapt to our situation. I guess you could say that I’m a closet environmentalist.

How does place—both temporal and spatial—factor in to your work?

Place is important to me and obvious in my work. I think that anyone who pays attention, and who knows themselves, will find themselves living in a place that resonates with them. Place resonates with people on multiple levels—for physical reasons, such as climate and landscape, and for emotional and intellectual reasons as well. If not, they will travel or move to a place that will either consciously or subconsciously fulfill this for them.

I grew up in the Midwest, in Iowa. I left after high school to go to school in Arizona. I traveled to and lived in Mexico. I live in Phoenix, Arizona now. It is the sunshine, the light, the mountains, the Sororan desert, the language, and culture that factor in every part of my daily life, and my daily life is what shows up in my work. If you look at my work, place can’t be separated: you can see the desert, the colors, and culture of Mexico and the Southwest. Personally, when I think of “place,” the important place with a capital “P” is the place in our hearts and minds. What is our place in the world, what do we want to see in the world, what do we want to be in the world, what do we have to say in the world, what do we have to offer the world?

What function does written language play in your work?

One of my pleasures and interests has been reading, specifically Latin literature. Now, with little children in our family, I don’t get to do as much of it as I would like. Maybe that’s why I’m so choosy about the books I read to our kids, because we are reading alongside them daily. I think the written language is another layer of information, even if it’s in a language we personally can’t translate. It implies and takes into consideration the existence of another view, another culture other than our own. It pulls us out of our comfort zone, makes us pause and question, perhaps even recognize something familiar. The spoken language has cadence and inflections, song and rhythm. Even if the text is not spoken, it is read, or kind of read, and the mind processes this alongside an image and makes associations, some more obvious than others. When I incorporate text into my work this is what it does for me, and what I hope comes across to the viewer.

What informs your choice of medium?

I suppose the answer would be “life.” I have been trained in printmaking, painting, drawing, ceramics, sculpture, graphic design, and illustration. Different times in my life, and different projects dictate different choices of medium for me. Illustration and graphic design were dominant when I was working at a newspaper in Tucson for four years. That was a time not too far in the distant past when newspapers actually had an artist on staff. Many of my skills in printmaking informed my black and white illustrations for the Sunday Op-Ed pages. Then I quit that job to pursue my fine art painting and to travel and live in Mexico for a while.

Then life happened again, literally, and I gave birth to three little people, now six-year-old twins and a seven-year-old. So, as anyone who has had children knows, everything changes, and time management becomes key. Now when I step into my studio, everything is more measured and prioritized, on a different level, which is good, and I think better. Although I have about three paintings I’m working on now, it’s printmaking that has become the dominant medium for me. And I think this is because I can see immediate results, as my paintings take a long time to build up and finish.

You’ve written that you look for the “communication that happens [between] the internal and external landscape of human experience.” How does art facilitate that communication?

For me, visual art facilitates this kind of communication because it’s so broad and subjective for the viewer. The reaction to visual art is also very immediate, and judgments and impressions about the art are made within seconds. In the arts of literature and music, judgments and impressions take a bit longer and can be built upon as long as the music plays or until the story ends. So this is my challenge as a visual artist. To communicate my personal views or interests that come from an internal part of myself, and to express that idea or feeling in an outward, tangible image—and all this to connect somehow, on that internal level, with the viewer in that instant.

We all have internal and external dialog going on all the time. And we all choose to express this differently. This is the basic human experience as I see it. Some are more honest and authentic with themselves about it than others. Sometimes I’m successful at achieving this, sometimes not so, but I believe this is the real work we do with our lives.

Teresa Villegas lives and works in Phoenix, Arizona. She is a fine artist, published illustrator, and graphic designer. Literature and language are often incorporated into her work. Her work has exhibited in Mexico and throughout the U.S. To see more of her work, visit www.teresavillegas.com.

Lindsay Stern‘s work has appeared in American Circus, Weird Fiction Review, PANK, and The Faster Times, among other publications. Her first book, Town of Shadows, was published in August 2012.