In this month’s poetry feature, ZACK STRAIT talks with RICHARD SIKEN about influences, confrontation, readers, accountability, sacrifice, balance, surface beauty, deep meaning, writing, and Waffle House.

– Zack Strait

Zack Strait (ZS): In your interview with Bethany Startin, for Black Warrior Review, when asked about your first memory of discovering and loving a poet or poem, you replied, “Unfortunately, none of my first memories are good.” Later in the same interview, however, you said, “I would like to touch Berryman’s shoulder, or Rimbaud’s forehead.” You have also named Jack Gilbert as one of your heroes in “Nerve-Wracked Love,” your profile in Poetry, said, “Gertrude Stein and Thomas Pynchon rattled me,” in “The Doubling of Self,” your interview with Peter Mishler for Tin House, and, on X, that, “Dennis Cooper is [your] Richard Siken.” Do you remember the first poem you loved?

Richard Siken (RS): When I was little, my parents let me play with a tape recorder. They gave me my own empty tapes. I was really young. I was able to read but I had to go to bed around sunset. I mostly sang into the tape recorder but there are a few tapes where I pretended to have a story time radio show. I had a big book of children’s poetry and I would read poems into the recorder and then apologize for them. I didn’t love them. I was drawn to them but there was something wrong with them. I told my listeners all about it. My junior year of high school, we spent two weeks on poetry. It wasn’t long enough. I asked my English teacher for a reading list and I spent a semester in the library. I didn’t find what I needed. In college, I didn’t study English or literature. I studied psychology and cultural anthropology. There was something about poems, stories, and songs that I was poking at. They were evidence of something. They were strategies. It didn’t occur to me that I should love poems. Poems were facts. Then, somehow, I stumbled across Dennis Cooper’s book of poems The Tenderness of the Wolves. It was fire. I would read a few pages and then I’d feel like throwing it against the wall. Is that love? I think maybe it is. There was a level of honesty to the poems that I had never encountered before. It was confrontational. It made me furious. It had cracked something open on a fundamental level and it was pretty clear that things were going to get really difficult for me. There was an obligation inherent in the confrontation. There was a dare to live more boldly.

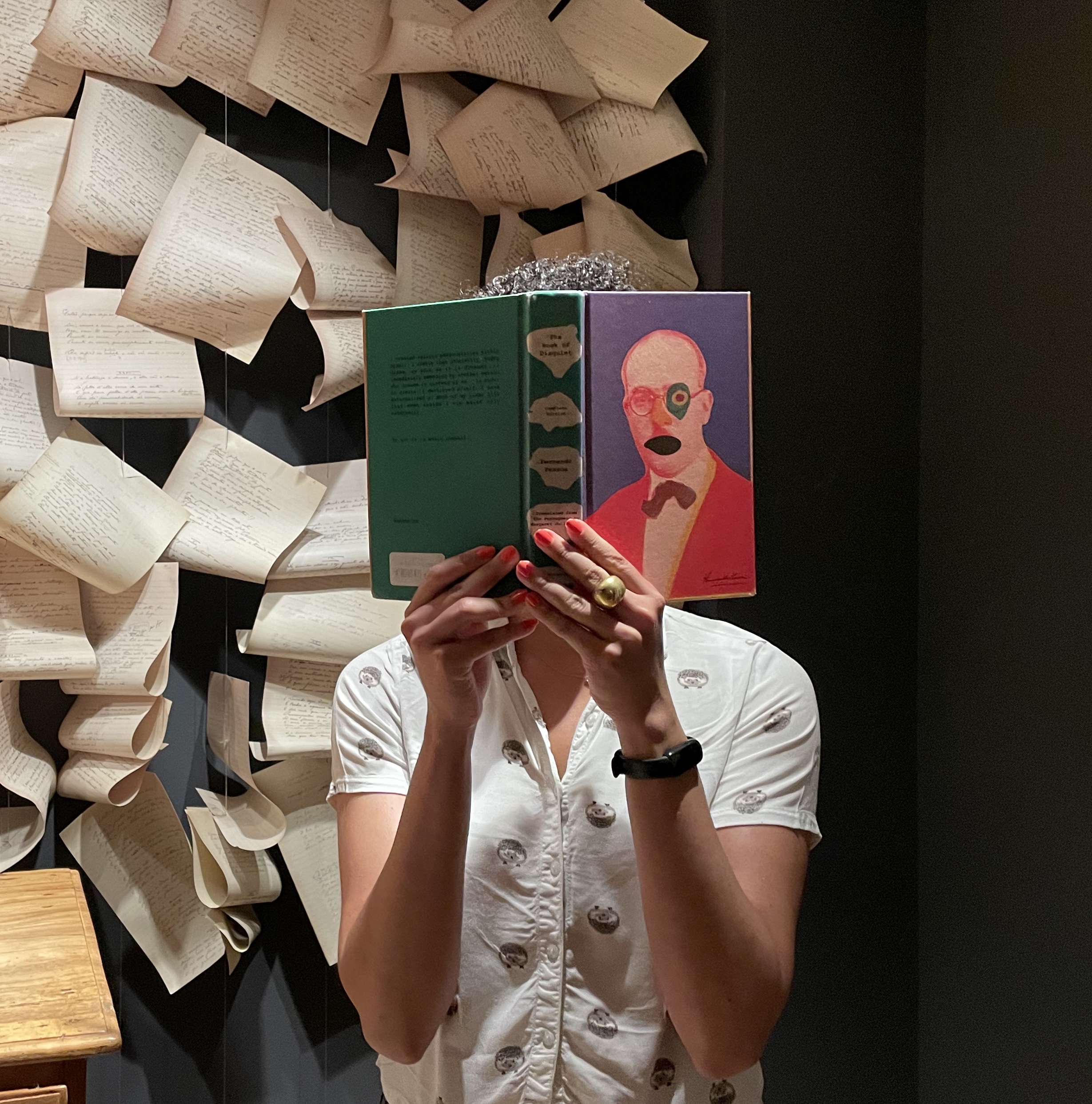

ZS: You confronted your big book of children’s poetry. You were confronted by Dennis Cooper’s poems. In your interview with James Hall for Gulf Coast, “The Poetry of Hostile Witness,” you cite the performance artist Laurie Anderson, the artist David Hockney, the writer and critic Samuel R. Delaney, the artist Robert Rauschenberg, the writer Kathy Acker, the musician David Bryne, and the filmmaker David Lynch as artists who created art which represented a self you did not see represented by most other artists. In your second collection, War of the Foxes, you include poems in response to the painters Picasso, Raphael, and Caravaggio. In your interview with Thomas Hobohm for The Adroit Journal, “A Conversation with Richard Siken,” in speaking about the composition of the poems for I Do Know Some Things, your third, forthcoming collection, you say, “The artifice was gone. I was saying things without metaphor, which was shocking and uncomfortable. I was speaking in the first-person, not making the reader complicit with the second-person or using the third-person to throw my voice. And most terrifying to me: the content was autobiographical.” Are artists, and their art, by extension, confrontational by nature, even if only with themselves?

RS: Yes and no. Artists take materials and manipulate them. So, fundamentally, the endeavor is confrontational. An artist confronts the marble, the pigment, the words. I think the artist also has to confront their cultural location in space and time. They have to confront where they’re putting their attention and how they’re presenting their vision. There are many ways to approach this. Some attack, some negotiate, some surrender to luck or chance. There are traditional, formal ways to make something powerful. They confront the materials in familiar ways. Proven ways. The artists you listed, the ones I’m drawn to, were more aggressive. They pushed against what came before. I’m not so severe in my thinking that I insist an artist must innovate, but they can. I like the ones that do. I think artists also have to confront their previous work. The fact of it. They have to admit that they live in a world where that art exists. You can argue that every work is in conversation with other works, that it’s informed by them. That’s a milder way of presenting the interaction. I think confrontation and innovation are part of my subject matter as well as part of my process, so they’re more apparent in my work. In my experience, the easiest way to lose faith in yourself is to compare your work to the greatest work of all time. The most invigorating thing you can do—for inspiration and motivation—is to look at art you don’t like. I like reading poems I hate. It reminds me that I have something to say and a way of saying it. It’s another kind of confrontation. Another successful one. Picking a fight for the sake of fighting doesn’t do anything interesting. Disagreeing with a premise or an approach is incredibly generative.

|

LANDMARK All night, all the cities in the thickening darkness. All night, all the roads. All night, all the houses with their punched-in eyes in the sickening, sickening darkness. I slept on the roof. I slept in the yard. I slept in the closet, under the cuffs of a dozen shirts when I thought there was something in the room with me. There was nothing in the room with me. I slept. O pioneers, I kicked in doors. The sound of hooves. We must not tarry. Night has descended and all its stars, they crackle and burn while I am left here, silent in the dimmed arena. I swear to god, there must have been a day on the beach or a secret dip in the lake after dinner. I must have walked all night against the wind once, trying to get somewhere. There must have been. I slept on the plaid couch. I slept in the house with the red kitchen. I fell out of bed and slept on the floor in a square of astonishing moonlight. I crawled there, hand over hand, from the darkness of a terrible dream. Believe me, something is heaving, incomprehensible. The house is filling up with strangers and the picture frames fall off the walls. There isn’t a word for it. Metal, powder, rust, a pear; even here a night flight, a tense change, struck like a bell. What’s that in your drink? Have you been here long? O why won’t you love me, love me? There isn’t a word for it, moonlight, slippery. There isn’t a word for it, moonlight. Through every window at once. I concentrated on the moon. I dug a hole in the sky and called it the moon. A hole in the sky and we call it the moon. |

ZS: Though your poems are confrontational and innovative, they are not so at the expense of your readers. You told Z. L. Nickels, in your interview for BOMB Magazine, in reference to how little poetry you publish (about 60 pages every ten years), “I don’t want to waste anyone’s time.” You also said, in the same interview, “My job is to write the poems, not judge them. Once they’re finished, they belong to the reader, not me. If they work, it’s because they’re about the reader, not me,” and, further, “The work should work, or not work, without me.” In the aforementioned interview with Peter Mishler, you echo these sentiments when you say, “I’d like to see poetry become as integral and common to life as music is. . . . I’d love to see it understood as something available and enjoyable.” In what ways do your readers, and your desire for poetry to, again, be an integral, common part of life, inform the choices you make as a poet, both in how you write your poems and which poems you choose to release into the world?

RS: I learned my multiplication tables and parts of speech from a series of animated musical shorts called Schoolhouse Rock! They aired between the cartoons on Saturday mornings. I also learned a little bit about science, economics, history, and civics from them. I did not learn about figurative language, emotional intelligence, or lateral thinking. Today, there are great tutorials on YouTube for almost everything, from baking focaccia to makeup application. There are no good tutorials for making metaphors. When and where are we supposed to learn about metaphors? For a while, I thought I wanted to study art therapy. Not long after I started, I saw a fundamental flaw: we have taken the arts out of daily living and it has made us limited and sick. Art therapy is an attempt to leak a small amount of the arts back into “regular” living. Withholding something vital and repackaging it as a solution isn’t healthy. Spending an hour twice a week trying to be creative under someone’s supervision isn’t an effective or therapeutic approach to building a satisfying life. I think I might have to do it myself—make the figurative language tutorials and post them on YouTube and TikTok. I think I’ll have to write essays as well. And there should be a comprehensive textbook, not focused on crowns of sonnets, but on analogies and associative leaps. Scientists could benefit from it. And lawyers. And basically everyone.

So that’s the first part, making poetry (and its strategies) a common part of life. The second part is what I have to consider, given the state of the world and its relationship to poetry, when writing and sharing poems. I think there are problems that we, as poets, have to address immediately, even before we start writing. For whatever reason, people come away from their first encounters with poetry deciding that they don’t understand poetry, and that perhaps it isn’t something worth understanding. And those willing to give it a chance are impatient and stingy with their time. So, what can we do? Give them candy, lots of candy. Go heavy on the front end. Delete the wind-up and the pitch and start with the crack of the bat. Give them image and music. Give them delight and surprise and swerve. You have to lock them in at the beginning or they won’t follow you. And you can’t let it sag or falter. You need multiple propulsions. You need the new propulsion already in place before you let go of the current one. People will go to great lengths to avoid feeling difficult things so you have to reward them for putting up with the discomfort. People have limited attention, limited bandwidth, so you have to cut every dead word and every false gesture. It has to be relentless and inevitable. It has to be economical and precise. And, above all, it has to be compressed. You have to get as much as you can into their heads before they turn away. A poem can be 100 pages long, but it has to be a 500-page poem compressed into 100 pages. As for how I choose which poems to release into the world, I think I’ll try to address that as part of a future answer.

|

GUESTHOUSE James wouldn’t let me move back into the condo because there were too many stairs, so he moved me into a one-room studio while we figured out what to do with me. It had brick walls and concrete floors. There was a sink and a small fridge. It used to be a one-car garage. The owner had added a bathroom in the back. It was one step up from the main room. Everyone was worried but I had practiced doing steps in rehab. I could do four of them without getting muscle cramps. The first night was hard. I slept on the floor so I didn’t fall out of the bed. I left the bathroom light on. The second night wasn’t any easier. Or the third night. A series of friends were commissioned to make sure I ate. Someone came by every evening and took me to a restaurant. The rest of the time I was on my own. The single step to the bathroom wasn’t a problem but getting in and out of the bed was tricky and the bed didn’t have rails. It made me uneasy. I slept on the floor. The plan: Get on with it. During the day I slept or did my exercises and practiced using my walker. Even when my leg gave out I could keep myself from falling, which was nice. I couldn’t get my walker in the shower, so I sat on the tile floor to soap up and rinse. It was hard to stand up so I would crawl out and lay on a towel until I was dry enough to pull myself up to the toilet without slipping. In the evenings I would go out to dinner with someone and I would have to ask uncomfortable questions: Where did we meet? How do you spell your name? Why did you like me? And then there were the questions I couldn’t ask: Did we love each other? Did I do bad things? Should I be ashamed? I cautiously circled the blank, struck-out spaces. I forgot most of what they told me once I got back to the guesthouse. It wasn’t a real house. I didn’t have a real body. I feel like there’s more to say about it but there’s not. |

ZS: Expounding on this idea of poetry as a vital part of living, you told Hilli Levin, in your interview for Bookpage, “Poetry is an example of how to be human. And I believe poetry is the language of the imagination. And we need larger imaginations. Figurative language reframes problems and offers previously unseen solutions. It challenges as well as delights. Poetry should be everyone’s second language.” Earlier in the same interview, you said, “I think poetry has too often been presented as a puzzle that needs to be solved to get to a deeper meaning. There can be deep meaning and surface meaning and sideways meaning, beautiful lying and sudden honesty, risk and tension and complicating frictions, and quite frankly, joy inside a poem. It isn’t supposed to be intimidating, it’s supposed to be electrifying. If a poem makes you feel stupid, it’s probably a bad poem.” This seems to present other facets of the problems you say need to be addressed by poets. If poetry is so fundamental to human existence, and the reading public is already, at best, skeptical of poetry, do writers and editors need to hold themselves accountable, or be held accountable, for what poems they choose to publish?

RS: My friend Drew Burk is a bookbinder. He came into the coffee shop and he was mad, sort of breathless and riled up. He had been making beautiful, hand-made blank books and no local bookstore would carry them. On the walk over from the last bookstore, he had decided that we were going to found a literary magazine. I would be the editor and find the text, he would construct the books and get them into bookstores because they would no longer be blank. I was surprised. It was unexpected but not really a bad plan. I started throwing out ideas about editorial focus, submission process, logistics, and timelines. I started making a two-year plan. He said I should call all my friends, get what I could, and we would be able to publish the first issue of our lit mag in three months. Which is what we did. We were new, we had limited reach. We knew we couldn’t get top-tier work because we couldn’t do it justice. We liked first books but authors with first books needed more attention than we could provide. We decided we would support writers working on projects that came before a first book. We were going to call ourselves Zero Books. We were going to publish glimmery failures—work that wasn’t perfect but showed promise, showed moments of brilliance. We would be talent scouts. We ended up calling ourselves Spork, because a spork is a hybrid thing that doesn’t really work.

Our obligation to our readership was to explain the project, to provide an angle of approach. Every issue was bookended by my “Editor’s Pages” and Drew’s “Notes on Construction.” I explained why I picked the work I did, Drew explained how he made the object. (We changed the format and materials every issue for the first few years.) These explanations fulfilled the obligations of our accountability. There are many other ways of being accountable. Some editors don’t know what they’re doing. They go on gut. They get lucky sometimes but they are unreliable. Other editors can’t explain what they’re doing but they succeed because their impulses are good. So: accountability. The writer has to present work that is intended to be shared. Writing in a secret shorthand. Writing indulgently, writing about things that are only relevant to the author is problematic. A poem doesn’t have to be understandable, that’s a trap, but it needs a reason for its presentation. It needs a goal, and hopefully the craft choices will support that goal. If a poem doesn’t know what it’s doing, or it undermines itself, I think it’s hard to justify publishing it. Experimentation leads to both innovation and failure. Publish the innovation. For the failures, be encouraging with the writer but share why you think it isn’t ready (or appropriate) for publication. An editor is like a waiter. A writer is like a cook. As a waiter, sometimes you’re presented with a plate of food you just can’t send out to a customer. As a cook, sometimes you make something inedible, just to see what will happen or to test a new technique. It’s important work but it shouldn’t leave the kitchen. I should probably mention that when we started Spork Magazine, Drew and I were working together in the same restaurant. I was a waiter, he was a cook.

ZS: You were writing poems that would appear in your first collection, Crush, while you were a waiter. Drew Burk was handmaking beautiful, blank books while he was a cook at the same restaurant. Together, you founded Spork. You told Thomas Hobohm, “The concept of the starving artist has been misunderstood. You can choose time or you can choose money. You can want less or make more. You can get a used car and work four days a week, or take a longer vacation. Some people think you’re starving if you buy a shirt from a thrift store. The concept of “want less / make more” is the concept of a balanced life, not a life of extreme practice and abject poverty. You shouldn’t sacrifice your well-being for your art, you should sacrifice your expensive tastes. Buy a new tube of paint and eat a sack lunch. Art isn’t fueled by trauma, it’s fueled by curiosity. Unfortunately, we’re most curious when our backs are against the wall and we desperately need a solution. You can look for a solution when you’re feeling fine. It can be an exploration instead of a knee-jerk reaction. Another misunderstanding about the starving artist: you don’t have to make art all the time. You can lie fallow and feed your head. There’s a necessary balance between transmitting and receiving. You can think about art while you are doing the dishes.” You told Peter Mishler, “It’s almost impossible to convince anyone that you can make something when you’re healthy, or just because you want to.” Would Crush exist if you were not living a well-balanced life, sacrificing luxuries for your art?

RS: Crush was difficult to write. The more I strayed from health and balance, the longer it took to write the poems and the worse the poems got. I needed time to write it. I could have been better to my friends, spent more time with them. I could have slept more or made more money. I was determined to make it exist. Many people were disappointed when I would choose a night of writing over a night with them. Some wouldn’t put up with it and left. I had some painter friends. I would sit in their studios and read or write while they painted. Hours would go by without talking. We would take breaks, talk about our projects a little, then get back to work. When artists in different disciplines discuss their work, it cross-pollinates. A writer can’t steal a painter’s ideas but writers are always stealing from each other. I bought my clothes at thrift stores, had roommates, and the bills got paid. This is very different than living through the experiences I address in Crush. There was no balance during those experiences. But I wasn’t writing poems then, not really. I was writing scraps and taking notes. If you aren’t healthy, you won’t have stamina. You won’t be able to maintain your momentum. If you are in crisis, call 911. Don’t write a poem about it.

|

HEAT MAP The neurologist takes out a folder, a picture. He points at my brain with a finger, says here. It looks like a map of a city on fire, a snapshot of weather. It creeps me out. He keeps saying damage. He is speaking slowly and being very clear. In my bag, at my feet, are two little notebooks. I could point to the sections that show the same thing. The breach, the rupture, the picture of it—there are things we shouldn’t have to see. Why would anyone want to see the inside of anything? I think about my brain. The metaphor of it. I think about my heart. The metaphor of it. I think about looking at the earth from space. No monkey was ever supposed to see that. Nauseating. I ruined myself with bad living. He isn’t saying it but he’s saying it. The microscope, the telescope, the magnetic resonance imaging machine. We pry open the black box. It’s nauseating. My heart is beating, my heart is always beating. I can’t stand the feel of it. It rattles me. My arm is heavy. My leg is numb. I can feel my breathing. If I can’t live in my body or my head then where does that leave me? He is talking and I am nodding. I’m waiting for him to tell me that isn’t going to happen again. He isn’t saying it. I stop listening. |

ZS: In your virtual panel with the poets Jason Schneiderman and Aaron Smith, for The Gay & Lesbian Review, in speaking about art, you said, “I think many people concentrate so hard on the icing that they miss the cake. Personally, I like the cake more. I chose poetry over film, over dance, over fashion, over a variety of other modes of expression because it deals with the cake.” What about the “cake” makes poetry worth sacrificing sleep, money, and even friendships, to create?

RS: Poetry is a process as well as a product. It’s a method for understanding the world. There’s the Socratic method (question and answer), the scientific method (hypothesis and testing), and then there’s the artistic method (expression and association). Well, we might as well call it the artistic method. We don’t have a good, common term that we use to address it. Math is the most accurate language we have for describing the world, but sometimes we don’t need accuracy, we need relation and approximation. That’s poetry. Poetry is a mutation of the language that allows for evolution. We can expand a body of knowledge with logic. We can expand a body of knowledge with experimentation. We can expand a body of knowledge with lateral thinking and comparison. Poetry (in fact all art) develops sideways and makes new connections. A poem can be as powerful (and necessary) as a syllogism or a formula.

I had a stroke a few years ago. I was paralyzed on the right side of my body and I forgot everything. I lost all my strategies and had to build back from scratch. I had to relearn my nouns and verbs. I had to relearn how to walk. To heal, the brain has to make new connections to compensate for the damaged areas. It’s called neuroplasticity. These new connections aren’t a metaphor. The body can actually build new structures, new pathways. It’s amazing and kind of gross. (It’s hard to think about your own head without feeling a little queasy—a suitcase full of meat that thinks.) The number of connections you make, and the strength of those connections, will determine the extent of your recovery. My neurologist said I made a fast and strong (and unexpected) recovery because I was a poet and a painter, because I knew a few languages. I had multiple engines, multiple strategies for making meaning. I had already been building new synaptic networks.

Poetry can be decorative. There’s a place for (and an audience for) sheer embellishment. That’s the frosting: the surface delight. But there can be more serious things going on underneath the surface. That’s the cake. Personally, I think both are necessary. Many people believe that poetry is just a pretty way of saying something. I think poetry can (and should) have greater stakes, risk more, move the fulcrum of perception just enough so that the world becomes strange and bewildering.

All of that is one answer. There’s another answer that’s just as true: I wanted to build something cool. I wanted to build something that would get me makeouts and high-fives.

|

WHITE NOISE I had a few minutes to get across the room and out the door once I set the alarm, which was still difficult to manage with my walker. The room was huge. It was the front half of a big metal warehouse we had converted into studio spaces. We shared it with other people but Drew and I were the only ones who used it at night. I couldn’t remember four numbers in a row, so I had the code written down on the wall, which defeated the purpose. I left the lights on and locked the door with the window and the metal screen door. My car was parked out front. I hadn’t driven it in months. Across the street was a mobile-home park. There was always someone fixing their car or having an argument. It was better to have people around. It made me more comfortable. Outside the door was a dirt parking lot. I used the wheels of my walker and left a trail behind me. Then a span of gravel, and I had to lift my walker to move it forward. Lift it and set it down, lift it and set it down, all the way to the curb, where the ground dipped sharply to the street. The grocery store was across the street. It was an access road, really. Small and rarely used, especially at night. There wasn’t much traffic but once I started down the slope I wouldn’t be able to stop. I would need to guess well and commit. Then the grocery store parking lot, the sidewalk, the automatic doors. I folded my walker and put it in the grocery cart and used the cart as a walker. I went down every aisle, to practice walking. I got canned soup and premade sandwiches, vinegar chips, soda. I concentrated on my breathing so I wouldn’t get panicky. Then I made my way back across the street with the food in plastic bags tied to each side of my walker. Managing the incline on the other side of the road was easier but still awkward. By the time I was back at the front door, my legs were a little shaky. Most of the warehouse was used for dirty work. We had paints and inks and glues in the main room, but we had a little office for the clean work. I had a little nook where there was enough space to fit a chair between the long desk in front of me and long bookshelf behind me. I had stopped trying to read and edit. I concentrated on designing book covers. I didn’t understand the books we were publishing anymore. It was easy enough to draw pictures. When I got tired of moving the images around I would watch videos of alien conspiracy theories and eat cold soup out of the can. We weren’t supposed to sleep in the building, we weren’t supposed to live there, but it was cheaper than taking an Uber back and forth between the studio and the guesthouse. And I was scared. I was still scared of being alone. There were people there during the day and Drew was there in the evenings. When I got tired I would move the chair to block the aisle and I would sleep under the desk. I would play white noise to mask my snoring. Music was too much to handle. It was overwhelming, but I was afraid of the silence. In the silence, I could hear my thinking: the constant narration of how damaged I was. |

ZS: In the same panel with Jason Schneiderman and Aaron Smith, you encourage teachers to, “Tell [students] they can look around and write about mac & cheese, thrift stores, thoughts and feelings . . . .” Beyond this, and your belief in the importance of a poem having both surface delight and seriousness beneath it, is there anything else you would like to say to those who love poetry and aspire to write their own?

RS: It was the summer between my sophomore and junior years of high school. I had just switched schools the semester before. I had made a few new friends and I was learning a new house, a new neighborhood. I was just learning about poetry. I mean, really getting at the fundamentals. I was floored that you could use language for something other than conversation. The whole world seemed like a five-paragraph essay but poetry rubbed against that. It was contrary and rebellious. That summer it rained a lot, and hard. We had a 100-year flood. It washed out bridges. I saw a house on the edge of a swollen wash lose its backyard and then get swept away. I didn’t want to talk about it, I wanted to make somebody feel it. I started writing every day. I was very bad at it.

I experimented, knowing I would fail to achieve what I wanted to for a long time. There was no pressure, though. No one was watching. I tried making the parts first. I made 100 metaphors and threw them away. I made another 100. I tried to find one thing every day that I could describe in an interesting way. I didn’t try to make a complete, successful thing. I tried to make interesting sentences. I tried to break the sentences in surprising ways to make powerful lines. I would write without judging it. I’d fill a page and then return to it later and cross out as much as I could while still maintaining the essence.

Sometimes you have nothing to say. Other times you have something to say but you think you should be writing something ‘important.’ You twist yourself up by trying to force something to happen while something else is trying to happen. You have to get out of your own way. Sometimes the thing you have to write is doomed from the start, ugly and without power or resonance. You still have to write it. And you shouldn’t keep everything you write. You shouldn’t demand the beautiful and profound. You cast your net and get some fish. Some fish are bigger than others.

I just finished writing a very difficult book. I’m writing a science fiction soap opera porno right now. It’s a tragedy because no one can get their clothes off. I needed to write something light. I doubt it will turn into anything. Having ideas is great. Writing down your feelings is great. The act is important. The art comes in the revision, in the manipulation of the materials. Don’t share everything. And if you’re stuck, play with the materials and let something happen.

|

DAWN I woke up in the dark. The house was quiet. The cat yawned and stretched, curled up again. It was very early or very very late. I wasn’t clear on how the day reset. When is now? I lifted my stuffed dog out of the bed and hugged her with both arms. I walked through the house. I had never been in these rooms at night alone. The moonlight cast blue shadows on the ground outside the windows. Dust on the furniture in the extra bedroom: I sat on the bed. White shag carpet in the living room and a textured ceiling: I lay on my back and raised my legs, pretending to walk on the moon. In the kitchen, I couldn’t reach the sink. I stood on a chair and drank from the tap. It ran fast and cold. In the family room I turned on the television. Static. It was nothing but it moved and made a noise. I watched it for a while. I watched it for a long time. There was something sad about it. It didn’t have a story. Everything had run its course or hadn’t started yet. An active emptiness. A background radiation. I opened the curtains and looked out the windows, facing east. The house was on a hill. The driveway sloped down to the street. In the distance there were mountains. I stood there, waiting it for it to start. I stood there for a long time. |

ZS: When Bethany Startin asked you, “Do you have a particular place you go to write? Can you describe your absolute ideal writing location?” you replied, “I do what I can wherever I am, but given a choice: I did like the Waffle House off of I-10 in Orange, Texas, near the Louisiana border, Friday night, late September, in the far booth, after the local high school football team’s winning game.” What was it that made that Waffle House, at that specific time, ideal?

RS: They won the game. They were teenagers. They were fire. The room was incandescent, explosive. And there were waffles. Samuel R. Delany wrote a science fiction story called “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones.” It won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. In it, there are people called Singers—public poets with the ability to improvise a song to memorialize a major event. The first Singer witnessed a catastrophic earthquake in Mexico City and stood in the rubble for hours, singing the story of it as it happened. Soon enough, Singers began to appear in other locations in moments of significant disturbance. Some poets like quietude and hindsight. I think there’s a lot to be said for immersive pandemonium. I would like to be a Romantic poet, full of longing, swooning against a tree somewhere in the countryside. I think my yearning is a little more feral, my lamentations a little more brutal. I can type at home or write in my notebook in a coffee shop, but when I’m caught up in chaos and fireworks I get electrified with language and song.

ZS: Before we end, is there anything you would like to say to your readers?

RS: Dear readers, I hope you like the poems.

Richard Siken is a poet, painter, and filmmaker. His book Crush won the 2004 Yale Series of Younger Poets prize, selected by Louise Glück, a Lambda Literary Award, a Thom Gunn Award, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other books are War of the Foxes and I Do Know Some Things, forthcoming from Copper Canyon Press this year. Siken is a recipient of a Lannan Fellowship, an Arizona Commission on the Arts grant, and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.

Zack Strait lives with his wife and son in Georgia. He is the editor of Cottonmouth and a contributing editor for The Common. His work has appeared in POETRY, Copper Nickel, and Ploughshares, among other journals.