Curated by KEI LIM

This month’s picks span extraordinary circumstances, yet tug at the rather ordinary, or perhaps most relatable, of emotions. AFTON MONTGOMERY recommends an investigative nonfiction book that interrogates people’s relationships to forever chemicals, VICTORIA KELLY recommends the 2024 Booker Prize Winner that abandons plot and follows a 24-hour period of astronauts orbiting Earth, and MONIKA CASSEL recommends a docupoetics collection that weaves the emotional aftermath of the Vietnam War with the defiance of women throughout history and literature.

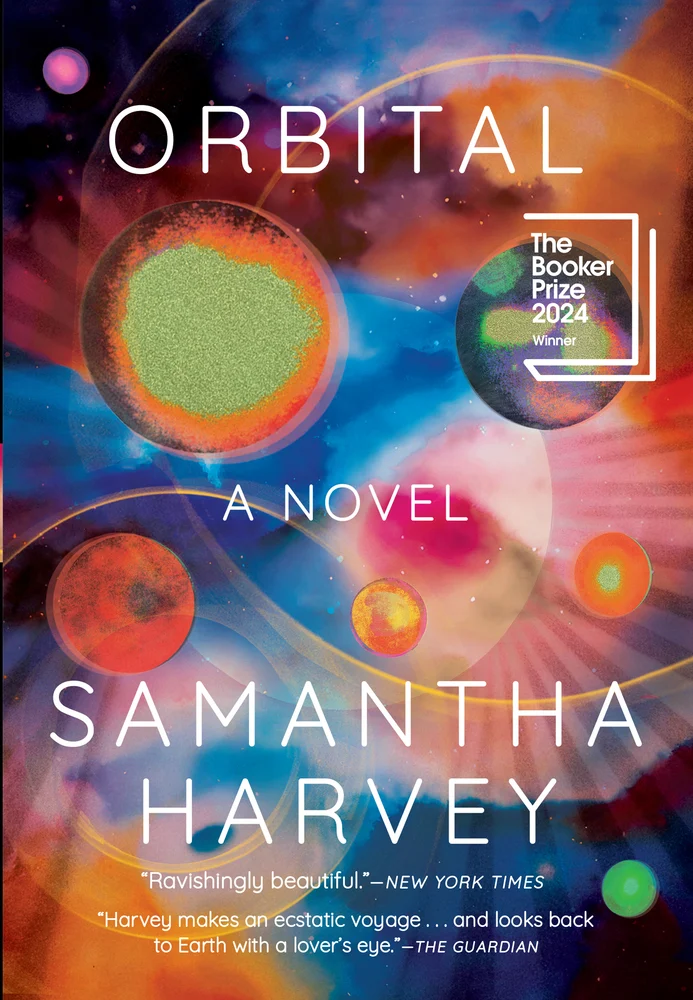

Mariah Blake’s They Poisoned the World: Life and Death in the Age of Forever Chemicals, recommended by TC Online Contributor Afton Montgomery

Some of my favorite reading experiences come from spending time in the worlds of deeply reported longform nonfiction. Maybe this feeling actually shares something with what people obsessed with fantasy novels experience. After all, a journalist does immense world-building to turn jargon and niche expert knowledges into language for laypeople, and in doing so they reveal to a reader a whole new landscape—it’s just one that also happens to exist right under our noses. This feels like one of the more generous things in the world to me, and these are often the writers to whom I’m most grateful—those who make the real world more real. In this vein, I can’t recommend Mariah Blake’s They Poisoned the World: Life and Death in the Age of Forever Chemicals highly enough.

Blake set out to understand and expose forever chemicals: what they are and why they’re in so many of the things we interact with every day, including our water. She traces their origin fascinatingly to the Manhattan Project and painstakingly walks a reader through the connection between nuclear weapons development and persistent government laxity on regulating PFAs and the like to this day. Like all the best investigative reporting, Blake draws you far into the lives of some of the regular people most affected by forever chemicals because of their lives at the intersection of rurality and industry, and your human connection with them makes a very complex historical text impossible to put down.

In a world as hard as this one is to live in just now, I know that most people are not inclined to pick up infuriating realism in their reading lives. Working in books, I’m inundated by the knowledge every day that what people want is to escape. To be clear: I think fiction is extraordinary. And I also cannot overemphasize how strongly I believe in digging into complication and specificity when an increasingly binaric political situation asks us to oversimplify everything—an act that can only do harm. Environmentalism and public health equity movements deserve writing like that in They Poisoned the World. They deserve the clarity of rage, and they also deserve supporters who understand the intricacies of how we got here exactly, so that there’s any tangible chance of moving into a different future. Blake’s book is the 21st Century’s Silent Spring, and it’s the book I want to hand absolutely everyone right now.

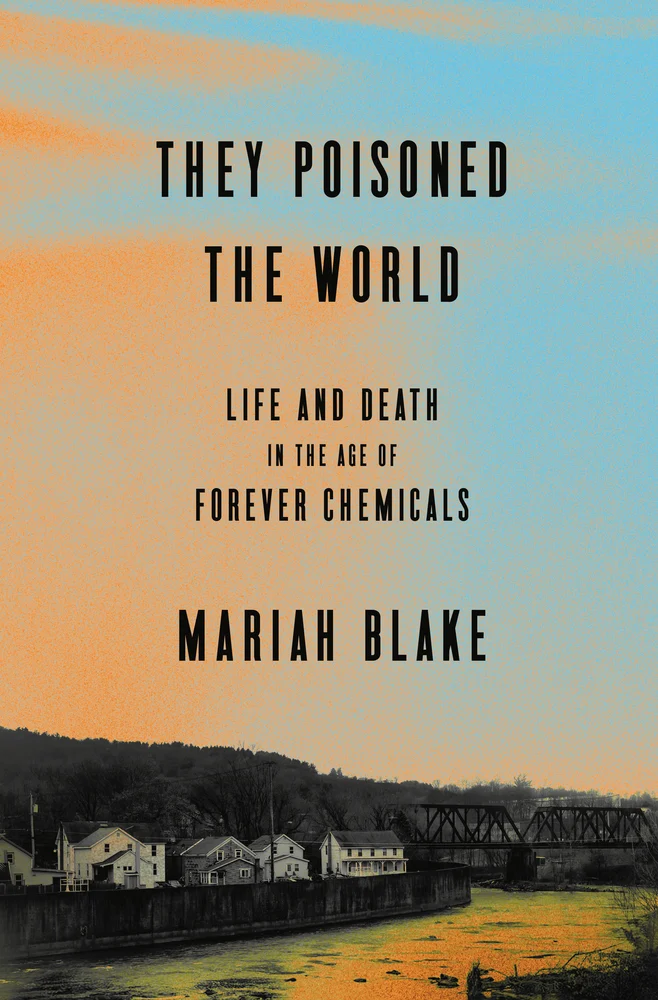

Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, recommended by TC Online Contributor Victoria Kelly

I picked up this slim novel (the 2024 Booker Prize winner) in the most beautiful bookstore in Japan, in the very sparse English section. I’m so glad I did—at a little more than 100 pages, this book is the most stunning, eloquent novel I have read in years. As a novelist, poet, and someone who devours books on spirituality, I savored its thoughtful and lyrical prose.

In Orbital, six astronauts from different countries rotate around Earth on the International Space Station. Worth noting: There is no “plot” to speak of, which may have turned me off the book before I started it, if I had known. But it is vastly worth reading, because what it is instead is more of a nonfiction-inspired meditation on life, beauty, loneliness, and love. I closed this book feeling inspired, hopeful about humanity, and changed.

The sixteen chapters represent the number of times the spacecraft orbits the earth in a single 24-hour period. As the point of view shifts between astronauts, they watch Earth turn slowly in their window and know that for the months they are in space, they are essentially frozen in time, spinning slowly and endlessly, while beneath them, all the people they love, and all the people they know and don’t are breathlessly living. Eventually, the astronauts “will reappear on Earth’s surface as strangers of a kind.”

Poetic phrases like “the soft brushed nickel of the Mediterranean sheened by the sun” and “the earth, a complex orchestra of sounds” infuse the text with a musicality and elegance. And the astronauts’ philosophical musings (“Humankind is not this nation or that, it is all together, always together come what may”) emphasize the almost religious experience they are having. While they are together in space, missing all the joys and heartbreaks and celebrations of humankind below them, they are gaining something much more profound—an understanding of how to never take it all for granted.

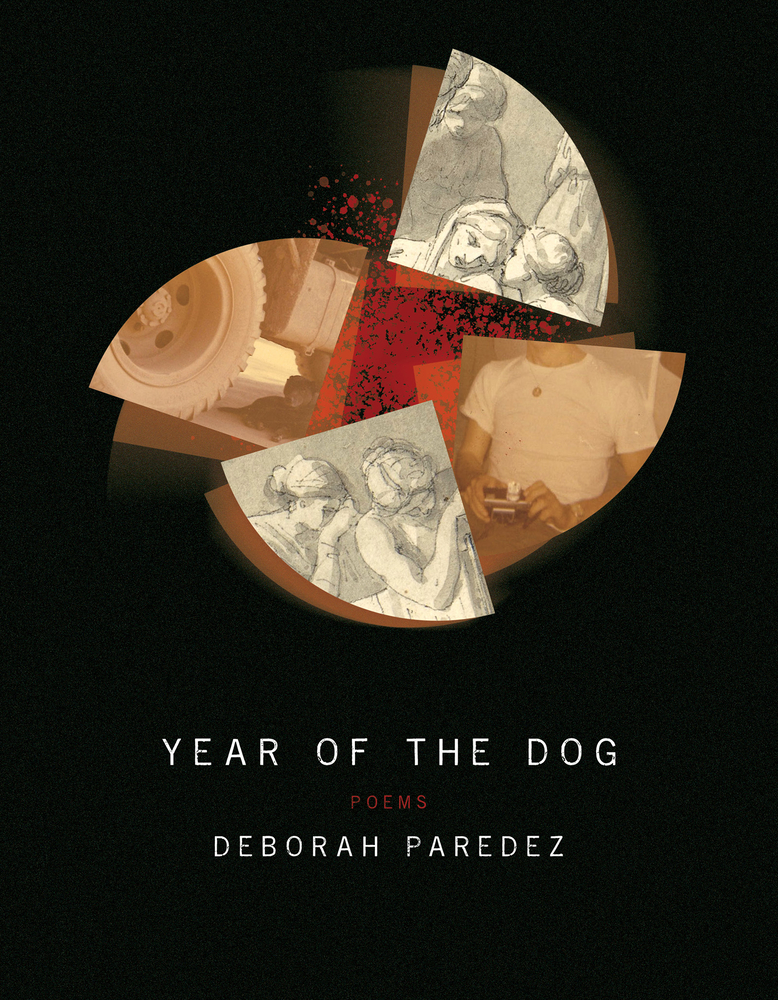

Deborah Paredez’s Year of the Dog, recommended by TC Online Contributor Monika Cassel

Just as I began reading Year of the Dog by Deborah Paredez, the United States Air Force Academy canceled a scheduled lecture by Paisley Rekdal about her 2017 nonfiction work The Broken Country, a book that considers transgenerational trauma among Vietnamese refugees and United States veterans of the Vietnam War. Rekdal’s lecture was pulled after the academy’s superintendent found comments she had made on social media about the U.S. President.

The policing of speech—and in particular, the suppression of voices perceived as critical to the regime—are about as alarming now as I remember seeing in my lifetime, but, as Paredez illustrates, they aren’t unprecedented: not in human history, not in our country’s history.

In an experimental collection that includes formal verse as well as documentary and photographic collage, Paredez amasses poems that draw kinships between unruly women, from Ovid’s Hecuba to Delia Alvarez, sister of the first American aviator POW captured in the Vietnam War. In “Self-Portrait in Flesh and Stone,” she writes, “Gloria Anzaldúa asks questions that are really refusals, How do you tame a wild tongue, how do you bridle and saddle it? How do you make it lie down?” We encounter Angela Davis, Antigone, La Llorona, LaNada Means, and Fred Hampton’s fiancée, Deborah Johnson/Akua Njeri: these women’s tongues do not lie down as they resist and give voice to their anguish.

The speaker’s father, deployed to Vietnam in 1970 (the year of the dog in the lunar calendar) becomes a central figure between these grieving, unsilenceable women, but he is reticent, seen most vividly when the speaker, a child, watches as he sleeps to make sure he doesn’t choke on his tongue from seizures resulting from his service. Fragments of his deployment snapshots and captions anchor the book visually, illustrating the war’s aftermath, not just for the speaker and her family, but for their larger community, given the disproportionately high casualty rates among Mexican-Americans.

The book’s emphasis on the image is most sharply apparent when Paredez links of two girls by iconic photographs taken of them, open-mouthed, and in anguish: Mary Anne Vecchio at the Kent State Massacre, and Kim Phúc, who became a symbol of the brutality of the Vietnam War when she was photographed, naked, as she ran from a napalm attack. (Six poems whose titles begin with Kim Phúc’s name comprise the center section of the book.) Open mouths—Vecchio’s, Kim Phúc’s, Hecuba’s, La Llorona’s—are repeated literary and visual motifs in this collection, which also includes collages of photographic fragments (most notably, arms, hands, and mouths). There are striking poems like “A Show of Hands,” “Armature,” and “Mother Tongue” that fuse proverbs and phrases in enjambed lines, like these about the speaker’s father: “out / of his hands / wringing a bird / in hand is worth two / in the bush he wasn’t so good / with his hands.” Paredez also writes about the May 14, 1970 killing by the National Guard of two peaceful protesters at Jackson State College. I can assure you that this event, at an HBCU, got much less—perhaps no?—air time in my 1980s high school history textbooks.

In her acknowledgements, Paredez lists the work of Don Mee Choi and Trinh T. Min-Ha as influences—I can see it, and if you don’t know their work, I recommend it too. Year of the Dog interrogates the limits of poetry while demonstrating the power of documentary work, just when we need unruly voices to speak against oppressive state power.