A trailblazer among American women at the turn of the century, Edith Wharton set out in the newly invented “motor-car” to explore the cities and countryside of France. As the Whartons embark on three separate journeys through the country in 1906 and 1907, accompanied first by Edith’s brother, Harry Jones, and then by Henry James, Edith is enamored by the freedom that this new form of transport has given her. With a keen eye for architecture and art, and the engrossing style that would later earn her a Pulitzer Prize in fiction, Wharton writes about places that she previously “yearned for from the windows of the train.”

Today we publish an excerpt from Wharton’s A Motor-Flight Through France, courtesy of Restless Books:

Fontainebleau is charming in May, and at no season do its glades more invitingly detain the wanderer; but it belonged to the familiar, the already-experienced part of our itinerary, and we had to press on to the unexplored. So after a day’s roaming of the forest, and a short flight to Moret, medievally seated in its stout walls on the poplar-edged Loing, we started on our way to the Loire.

Here, too, our wheels were still on beaten tracks; though the morning’s flight across country to Orléans was meant to give us a glimpse of a new region. But on that unhappy morning Boreas [Greek god of the north wind and bringer of winter] was up with all his pack, and hunted us savagely across the naked plain, now behind, now on our quarter, now dashing ahead to lie in ambush behind a huddled village, and leap on us as we rounded its last house. The plain stretched on interminably, and the farther it stretched the harder the wind raced us; so that Pithiviers [a municipality in the Loiret department of north-central France], spite of dulcet associations, appeared to our shrinking eyes only as a wind-break, eagerly striven for and too soon gained and passed; and when, at luncheon-time, we beat our way, spent and wheezing, into Orléans, even the serried memories of that venerable city endeared it to us less than the fact that it had an inn where we might at last find shelter.

The above wholly inadequate description of an interesting part of France will have convinced any rational being that motoring is no way to see the country. And that morning it certainly was not; but then, what of the afternoon? When we rolled out of Orléans after luncheon, both the day and the scene had changed; and what other form of travel could have brought us into such communion with the spirit of the Loire as our smooth flight along its banks in the bland May air? For, after all, if the motorist sometimes misses details by going too fast, he sometimes has them stamped into his memory by an opportune puncture or a recalcitrant “magneto”; and if, on windy days, he has to rush through nature blindfold, on golden afternoons such as this he can drain every drop of her precious essence.

Certainly we got a great deal of the Loire as we followed its windings that day: a great sense of the steely breadth of its flow, the amenity of its shores, the sweet flatness of the richly gardened and vineyarded landscape, as of a highly cultivated but slightly insipid society; an impression of long white villages and of stout conical towns on little hills; of old brown Beaugency in its cup between two heights, and Madame de Pompadour’s Ménars on its bright terraces; of Blois, nobly bestriding the river at a noble bend; and farther south, of yellow cliffs honeycombed with strange dwellings; of Chaumont and Amboise crowning their heaped-up towns; of manoirs, walled gardens, rich pastures, willowed islands; and then, toward sunset, of another long bridge, a brace of fretted church-towers, and the widespread roofs of Tours.

Had we visited by rail the principal places named in this itinerary, necessity would have detained us longer in each, and we should have had a fuller store of specific impressions; but we should have missed what is, in one way, the truest initiation of travel, the sense of continuity, of relation between different districts, of familiarity with the unnamed, unhistoried region stretching between successive centres of human history, and exerting, in deep unnoticed ways, so persistent an influence on the turn that history takes. And after all—though some people seem to doubt the fact—it is possible to stop a motor and get out of it; and if, on our way down the Loire, we exercised this privilege infrequently, it was because, here again, we were in a land of old acquaintance, of which the general topography was just the least familiar part.

It was not till, two days later, we passed out of Tours—not, in fact, till we left to the northward the towered pile of Loches—that we found ourselves once more in a new country. It was a cold day of high clouds and flying sunlight: just the sky to overarch the wide rolling landscape through which the turns of the Indre were leading us. To the south, whither we were bound, lay the Berry—the land of George Sand; while to the northwest low acclivities sloped away, with villages shining on their sides. One arrow of sunlight, I remember, transfixed for a second an unknown town on one of these slopes: a town of some consequence, with walls and towers that flashed far-off and mysterious across the cloudy plain. Who has not been tantalised in travelling, by the glimpse of such cities—unnamed, undiscoverable afterward by the minutest orientations of map and guide-book? Certainly, to the uninitiated, no hill-town is visible on that particularly level section of the map of France; yet there sloped the hill, there shone the town—not a moment’s mirage, but the companion of an hour’s travel, dominating the turns of our road, beckoning to us across the increasing miles, and causing me to vow, as we lost the last glimpse of its towers, that next year I would go back and make it give up its name.

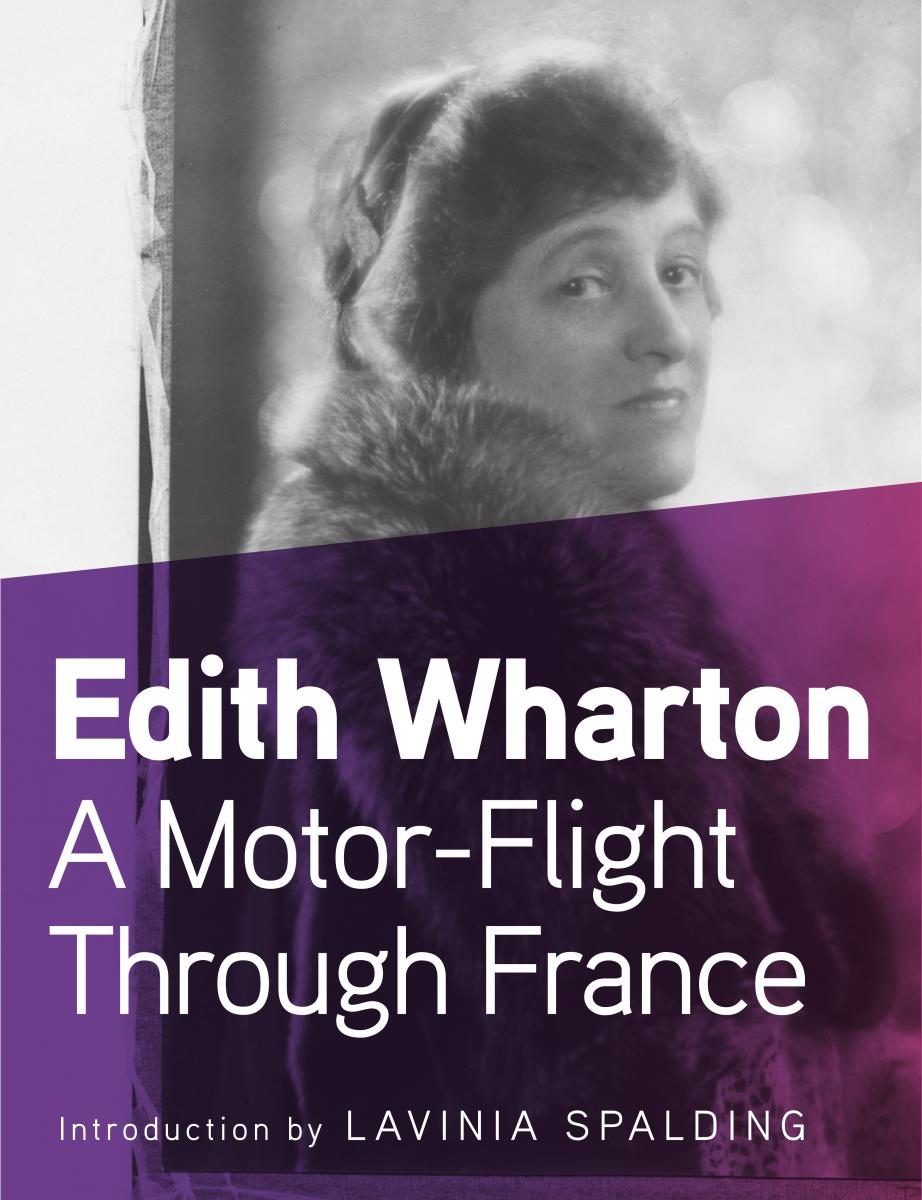

Edith Wharton (1862–1937) was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The author of more than 40 books in 40 years, Wharton’s oeuvre includes classic works of American literature such as The House of Mirth, The Custom of the Country, The Age of Innocence, and Ethan Frome, as well as authoritative works on architecture, gardens, interior design, and travel.

________________________

On Sunday, June 22, Restless Books will be hosting a very special book launch for A Motor-Flight Through France, the first title in its Restless Women Travelers series. The event will take place at The Mount—Edith Wharton’s gorgeous home in the Berkshires. Beginning at 5:30, there will be a short reading, conversation, and cocktails on the patio overlooking Wharton’s gardens, with fellow readers, writers, and travelers.