S. TREMAINE NELSON interviews ANGELA PALM

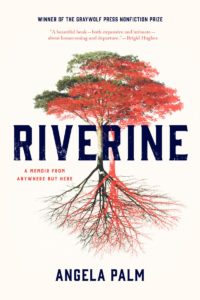

Angela Palm is a Vermont-based author, editor, and writing instructor. Her first book, Riverine: A Memoir from Anywhere but Here, will be published by Graywolf Press in August 2016. S. Tremaine Nelson met with Palm outdoors at a cafe less than a hundred yards from the shores of Lake Champlain in Burlington, Vermont, on the first warm day of spring this year. They spoke about Palm’s influences, class in Indiana, and the pervasive brokenness of the American criminal justice system.

S. Tremaine Nelson (SN): Here we are on a beautiful day near Lake Champlain.

Angela Palm (AP): Yes, it’s beautiful here.

SN: So how did you end up in Vermont?

AP: I wanted to leave Indiana. I felt like I had to leave to become my best self, to explore parts of myself fully. I also wanted to live somewhere socially progressive.

SN: Your book Riverine explores rural Indiana and takes us through a horrible crime committed by someone very close to the narrator. Are you still in touch with your childhood neighbor Corey, who features prominently in the book’s crime?

AP: Yes, I’m still in touch with him. We email every few weeks.

SN: What is his current legal situation?

AP: Corey’s living his life sentence without parole. He’s about to turn 38 and he’s living in the system as best he can.

SN: Is it a full sentence, or could it be shortened for good behavior?

AP: In his case, it’s the duration of his natural life.

SN: What’s your current communication with him like?

AP: I email him every two weeks or so. We have conversations and keep each other up to date on our lives.

SN: In your book you mention a new system of communication where inmates have to pay to use email, or even pay to use the phone.

AP: Yes, this is a major issue. The privatization of prisons in the US has become a major issue. It’s tied to the government, but it’s also a big business: an obvious conflict of interest. Phone calls have always cost money, but now they charge for emails. And you can also do video visits.

SN: Private Skype.

AP: Right. Ten dollars for each twenty-minute block. They’re making a lot of money off it and replacing in-person visits with digital visits, which don’t serve the inmates or their families very well. The physical closeness with people is so important.

SN: So let me ask you, then, if you feel that literature can be a vehicle for justice?

AP: Yes. I think we have an obligation as artists to some extent.

SN: The role of the artist to correct some wrong or injustice?

AP: It’s one role, among others. [Literature] can bring light to certain situations. If I have a place from which to pursue greater justices, or to correct injustices, I will.

SN: That’s an interesting double-edged sword for the artist. Consider someone like George Orwell who wrote what we might consider political propaganda. And yet we still consider 1984 and Animal Farm great works of literature.

AP: I think you can go over the top with messaging if it’s not done artfully.

SN: Your book and In Cold Blood by Truman Capote share certain techniques, especially how they both toe the line between fact and fiction.

AP: Right. As a culture we’re desperately interested in murder and crime in a way that TV glamorizes, and toeing the line of fact and fiction seems a natural consequence of that, or a natural mode of considering the realities of crime and the narratives of crimes. [Interestingly], when we convict people of crimes, the threshold for conviction is reasonable doubt and not certain knowledge. There’s inherently a gray area of truth. We know what happened, sort of, but maybe not how or why or who. Defenses and prosecutions build stories around a string of facts.

SN: Is there a specific book that made you want to be a writer?

AP: There is—Loving Frank by Nancy Horan. It’s a novel about Frank Lloyd Wright, the story of his life and demise, told through the lens of his client and lover, Mamah Borthwick Cheney. I love that era, not only its architecture and art, but the writing, too. I loved how the woman who narrated the book addressed these blurry lines between being an artist, a parent, a person in the world, an individual. It really inspired me. It motivated me to finally write my own book.

SN: Who is your favorite living writer?

AP: It changes. I love when writers do interesting and unexpected things with form and content and still manage to tell a good story. So, right now, for me, that’s people like David Shields, Dana Spiotta, Jenny Offill.

SN: Who is your favorite poet?

AP: I don’t think I can choose just one. A few favorites: Ai, Lucille Clifton, Anne Carson, Ross Gay, Kim Addonizio.

SN: If you could meet one famous dead writer who would it be?

AP: Virginia Woolf. I’ve always identified with her. Also William S. Burroughs because I want to ask him questions about his not quite being held accountable for Joan Vollmer’s death.

SN: Back to your own work: can we talk about the part of Riverinewhere you describe working at the bar called The River? It was my favorite part of your book.

AP: Yes!

SN: For me, the emotion you communicated in that section had such a powerful balance of nostalgia and melancholy. Your character knew it was a temporary place and a phase of your life because you were about to go to college.

AP: Right. It was a bittersweet experience. I really loved that place, and I considered it my education—not only of people and work, but of the world. It was a tragic place, too. It was sad to realize I would never stay there myself, but all those people I knew would stay there.

SN: Have you read The Liar’s Club by Mary Karr?

AP: Yes.

SN: That section of your book reminded me so much of that.

AP: I admire Mary Karr so much.

SN: It reminded me of the narrator being at the V.F.W. bar in The Liar’s Club. Those sections in your book almost felt like a homage to Karr’s work.

AP: It wasn’t intentional, but I see what you mean. Working in the bar [resulted in] one of the very first essays I wrote for the book. I wanted to focus on taking the temperature of a place from a particular angle.

SN: How did social class play out in the bar where you worked? The characters seem like they’re all from rural Indiana, but with some distinctions.

AP: There’s a rural upper class, even if people don’t typically recognize that.

SN: Landowners?

AP: Yes, and business owners. And where I was from that was the Dutch, people of Dutch descent. There were layers with the working class. Layers of working middle class and the working poor. My family has been the working poor and middle class.

SN: Did you perceive a sense of otherness as a consequence of that?

AP: I did, a sense of awareness of not belonging in either of the classes.

SN: Is that fuel for writing?

AP: It is. But it was the otherness I felt in my own family, more than the community in a larger sense. I always turned to art to write and create and to understand things deeply. I remember writing stories as early as the fourth grade.

SN: When you were a kid, did you have a job that you imagined yourself doing as an adult?

AP: For a while, I felt a deep passion for social justice. I specifically [wanted] to run a nonprofit center that worked to keep juveniles out of the criminal justice system— in response to where I was living and the things that I experienced. I was always enraged about injustices I perceived, but I didn’t know what to do about it.

SN: Is there a teacher who first influenced your writing?

AP: Yes, Bill Mottolese. He was Joyce scholar, an amazing professor who was my instructor freshman year. I was a criminal justice major and we had to take core classes. I was in his class, and he pulled me aside after we turned in our first paper. He said, “Angi, you’re a writer and I’m going to put you in the English program.” And I was like, “Okay, I’ll do it.” So I double majored in English and Criminal Justice. He taught me how to be a critical reader and that’s such a great skill for a writer. He was an impassioned teacher, he would jump on the desk shouting about solipsism, and there’s nothing better than that when you’re in college.

SN: What reactions do you want from readers after reading your book?

AP: I hope people will embody more compassion toward people who have done terrible things. Which is not to say that we should excuse bad behavior. But when you consider how many people we have incarcerated in the US it’s important to implicate ourselves in that process at the community level—recognize when someone’s slipping into something that could lead to violence, self-destruction, and think about how that path might be altered with a little more care, a little more love.

*

Angela Palm is the winner of the 2015 Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize. Her first book Riverine: A Memoir from Anywhere but Here will be published by Graywolf in August.

S. Tremaine Nelson is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and founder of The Literary Man book blog.

Photo credits: Headshot of Angela Palm by Greg Perez Studio, Indiana; image of rural Indiana from Creative Commons.