S. TREMAINE NELSON interviews MURRAY FARISH

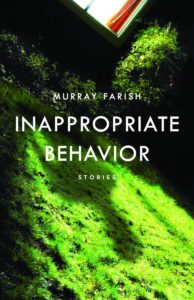

Murray Farish’s short stories have appeared in The Missouri Review, Epoch, Roanoke Review, and Black Warrior Review, among other publications. He lives with his wife and two sons in St. Louis, Missouri, where he teaches writing and literature at Webster University. Inappropriate Behavior is his debut short story collection. Murray answered the following questions via email.

S. Tremaine Nelson (SN): How would you describe your new fiction collection?

Murray Farish (MF): If I had to put into one sentence what the book is about, I’d say it’s about the economy, presidential assassins, theoretical ghosts, attention-deficit disorder, kinky sex, 21st-century portraiture, failed promise, conspiracy theories, Diogenes, aquatic larvae, religion, bafflement, secret societies, Dollywood, steamer travel, violence, politics, Jodie Foster, unemployment, constipation, wild parrots, small towns, suburbs, big cities, foreign languages, the perils of dog ownership, and, as Kerouac put it, the hard time had together by boys and girls in America.

SN: Throughout Inappropriate Behavior infamous historical figures, such as Lee Harvey Oswald and John Hinckley Jr., make appearances along with fictional characters. What sort of research did you undertake to imagine a young twisted John, or an anxious young Lee?

MF: I don’t know if it’s research, necessarily. I read a lot of stuff about presidential assassinations, especially the Kennedy assassination, but others, too. I’ve got a John Wilkes Booth story and a Leon Czolgosz story that didn’t make the cut for this collection, but may make the next one. So I knew a lot about these guys when I sat down to write the stories, but none of that historical data makes a human being on the page. So other than some basic factual stuff like getting the year Oswald sailed for France correct, I didn’t worry too much about the facts. I made these characters to do what I wanted the stories to do.

SN: I loved “The Thing About Norfolk.” Without giving away the lurid, voyeuristic details of the plot, is there something “wrong” with readers who (like me) loved this story?

MF: You mean as opposed to there being something “wrong” with the person who wrote it? In any event, I wouldn’t worry about it. There’s something wrong with all of us. And thanks for loving the story. Weirdo.

SN: Many of your stories shine light on the darker side of characters who seem innocent or unassuming. For instance, in “Ready for Schmelling” the narrator, Perkins, describes himself as a “simple man” before proceeding into an unusual situation. Who are your inspirations for subverting character types of this seemingly ordinary, unassuming nature?

MF: Or let’s take Tom and Patty in “The Thing About Norfolk.” I won’t give anything away, either, but what interests me about them is how, once they cross that one line, they can’t stop crossing lines. Same thing with Perkins—once he’s in, he’s in all the way, whether he knows it at the time or not. Transgression seems to be one of the subjects I’m stuck with as a writer. Once you cross a line, for good or ill, the old ways you’d learned to live your life by don’t work anymore, and you’ve got to make up a new life as you go. The pressure and tension and anxiety that creates in a person then creates pressure and tension and anxiety in the story. I don’t want anyone comfortable at any point, the characters or the reader.

SN: Your scenes about sex are credible, but also refreshingly comical (Perkins and Marcie, in particular, are endearingly manic in their love-making). How do you strike such a delicate balance between comedy and credibility in writing about sex?

MF: You’ve really got three choices when writing about sex, I think—you can write a play-by-play account, an instruction manual, or a joke. Given that choice, I’ll write the joke every time.

SN: Which short story writers do you most admire and what about their writing stands out?

MF: From the dead: Andre Dubus, for the depth and humanity of his people; John Cheever, for his orchestration; Eudora Welty, master of detail; Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of America’s great chroniclers of frenzy; Grace Paley, for her inimitable tone of voice; Barry Hannah, who sunk the hook in me; Chekhov, because duh. Among the living, I really dig Saunders, obviously, and Dan Chaon, Kelly Link. Elizabeth McCracken’s new book Thunderstruck is amazing—I mean, it amazes. T.M. McNally should be read by all. Lee K. Abbott is one of my true heroes in this world.

SN: How does the geographical setting impact your fiction? Does it matter that one story takes place in Virginia, for instance, whereas “Charlie’s Pagoda” opens in St. Louis?

MF: The stories are set in places I know—the South, Texas, St. Louis—just because I know those places. For the book as a whole, I like that it encompasses a lot of different places, but for individual stories, I think place is even more crucial.I want my settings to function like characters in the stories—just like people, places want things from us, places have expectations and desires. Place gives writers a chance to ground those desires in the physical.

SN: Do you have a creative writing maxim that you tell your writing students?

MF: I probably used to have more of these kinds of things than I do, but at a certain point they started reminding me of pre-game speeches in football. Coaches will tell you, pre-game speeches only last till the first time you get hit in the mouth. This writing game is going to hit you in the mouth, sooner and later, and maxims aren’t going to do you much good when it does. I tell them, read and write, all the time, and I try to be what my colleague, the great poet David Clewell, calls himself—a glorified resource department. If you can get the right book or writer to the right kid at the right time, you can make a real difference, whether that kid turns out to be a writer or not. But yeah, read and write, all the time—those are two things that creative writing students don’t do enough of. Because, how can you?

SN: If you could arm-wrestle any dead or living writer, who would it be?

MF: Probably Alexander Pope, because he was a little bitty dude.

SN: What are you working on today, and if you could change anything about the current state of American fiction, what would you hope to change?

MF: It’s summertime, so “working on today” becomes a really vexed topic. I spend my summers at home with two boys who are like something conjured up by an ancient Sumerian god to destroy the world as beautifully and poetically as possible, so I kind of got to keep a lid on that, for your good, as well as mine. As soon as school starts and I can turn them over to the state, I’ll get back to my stories. I’ve got one waiting on me about Richard Nixon’s days as a high school carny talker in Prescott, Arizona, one about the Everglades cryptid known as the Florida Skunk Ape, one about a guy who is convinced he was teleported as part of the Philadelphia Experiment. So I’m dealing with a lot of stuff… which doesn’t leave much time or interest in thinking about the problems of American fiction. Again, this is probably a question I could have answered “better” five or ten years ago, when I knew more than I do now. I’m a tad miffed that no one from Hollywood has sent me a big check yet, but maybe they’ll dig the Skunk Ape story.

Murray Farish’s debut collection Inappropriate Behavior is available from Milkweed Editions.

S. Tremaine Nelson is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and founder of The Literary Man book blog.