This feature is part of our print and online portfolio of writing from the immigrant farmworker community. Read more online or in Issue 26.

Part of a day’s harvest, 1985.

Bradley County, Arkansas

I stood behind the orthopedic specialist and watched the giant monitor where my MRI reports glowed. He traced the contours of my spine, his index finger waving back and forth down the screen. I had gotten his name after a months-long battle with neck and back pain. What started as fire and numbness in my right arm grew into a welter of spasm and neuropathy. This doctor was known as an oracle of back pain. He bragged of being able to guess how people used their bodies just from reading his screens.

The exhaustion of having a nameless, and, therefore, untreatable problem was eroding my spirit. I needed him to find the answer. As he squinted, he rattled off his wins, spotting the bone-wear patterns of golfers, softball players, fiddlers, and software developers. He stopped to identify the small bumps on each vertebra: bone spurs. It felt like he was stalling. Had I stumped him?

A spark seemed to run through him and he smiled. He swiveled in his chair to face me and balled his hands into fists, curling them a bit at his sides. He pulled his shoulders up and bounced slightly. “Between the ages of eight and twelve, did you do any load-bearing activities like this?”

*

The doctor was spot on, even if he didn’t know the name for that job: a bucket-toter. Tomatoes were the cash crop of my home region. Specifically, the “Bradley County Pink Tomato” powered a robust small-family farm system that is still the heart of a summer festival in southeast Arkansas. Now, only a handful of families remain over much larger “agribusiness” ventures.

I grew up in the 70s and 80s, the last era of small family-to-market farms. With not much other industry, our local radio station crowed its tagline, “From the land of tall pines and pink tomatoes.”

My parents, sister, brother, and I grew around an acre, sometimes two, of tomatoes for market. We did everything from seed to harvest, with the occasional help from a cousin or two. The season began early in the year, in a plastic-clad hothouse heated by a woodstove. I do not have tea-dipped madeleines to provoke memory, but the combination of potting soil, woodsmoke, and tomato seedlings is as strong a time machine as I need.

*

Other smells marked that life: tractor diesel and oil, fried-egg sandwiches eaten on the way to the field, pesticides, chicken fertilizer. The first sweat in the morning sun from each family member served as an olfactory signature. Those boldened by noon, into the stink of the afternoon. It always made sense that someone could smell “loud.” Other smells proved unwashable, captured in hair and nailbeds. Pruning the growing plants left every arm hair coated in a yellow-green film that stunk of acidic leaf-green. I loved the pond-ish funk from hissing Rainbird sprinklers. Later into the season, we all skirted the cull pile rotting in the sun. Visiting uncles always made the same joke: “Smells like money.”

*

I remember daydreaming of jobs in air conditioning. That was the main prerequisite.

People ask if I like tomatoes, or grow them.

As long as I can see the end of the row, I’ll grow them. More than six plants make me nervous.

My sister will not even keep a houseplant.

My brother’s story is for another time.

*

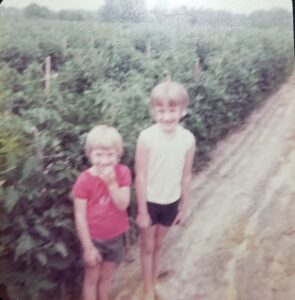

Gina and Michelle Castleberry, 1976.

The smallest kid, if worth their salt, could assemble packing boxes. I remember sitting in them to fold them complete around my scrawny self. If there were other kids around, it was a race. That was almost more play than work. Around first grade, a child could become a bucket-toter. While the adults picked the fruit, the toter waited for them to yell “Empty!” Then they would run like hell, or toss the empties to the pickers. Woe be the worker who struck a plant or picker with an empty bucket. Strong kids toted the harvest to the row-ends. Buckets came in five-gallon and ten-gallon sizes, but the rush of picking days usually meant they were over-loaded. I wanted to work like my older boy cousins, be called “stout.”

My sister and I advanced through the jobs, from boxmaker to pruner, from driving tractor to plow, then “poison,” then fertilizer. We picked tomatoes, brought them home to “dust” with a rag, to knock off the dust and pesticide. That was another kid’s job. The clean tomatoes were propped in front of Mama to sort into grades. Number Ones were like the tomatoes you see in the grocery store, fat and slick and uniform. Number Twos might be smaller and used in restaurants for salads. From there down you ended up with the Culls. Those forsaken fruit were bug-bitten, “cat-faced” and warped and ended up in cans. Also known as Unclassifieds. Call another kid an “Unc” and you would get a fight.

Finally, we had a chance to shower and rush to market. I remember a fizzy and wired kind of fatigue by that point in the day, late afternoon. The noise of the auction would whirl by us and Mama gave us turns handing the sale receipt through the windows of the buyer’s sheds. A manicured hand would reach out holding a check, accompanied by a blast of air conditioning and Avon Skin-So-Soft. We would deposit the check, go home, and start before sunrise again the next day.

*

Many of the farm life habits have fallen away. I still, though, enjoy the practice of saying a silent grace over a prepared meal. “Bless the hands,” starts the prayer I learned, speaking of the ones that made the meal. “Bless the backs,” I say to myself now, “and the hands that labored for this food.” I tell people who have never seen crops that any vegetable too fragile or soft to be picked by machine, was touched by a worker, for all of us.

*

My sister found hers first, the odd torque of her spine which made one leg seem longer than the other and gave her backaches. I found mine at the orthopedic doctor’s screen, a slight curve in my spine that makes my right shoulder lower and my right hip hitch upward. Sister’s is the opposite because she is a lefty. Those mirrored S-shapes are a tell written in our bones from that toting motion the doctor mimed.

My parents’ bodies are marked by their work, too. Mama’s hands need no scan to show the gnarled bumps of arthritis. I asked her to describe picking cotton as a girl on a sharecropper farm. She winced remembering the way the sharp “burrs” would prick the tender skin where the nail is connected to your fingertips.

Tommy Castleberry in the family field, 1987.

“It had kind of a rusty smell, hard to describe,” she wrote me when I asked, describing the plants. “It was back-breaking and knee-killing work (but I lived over it).” I could hear her laugh at that parenthetical. She took it in a stride that needs a Rollator now after a handful of joint replacements. During our farm years, Daddy would work with us in the tomatoes then leave once we started packing. He would lay brick the rest of the day. He didn’t retire from that work until he was over eighty.

I work as a therapist now. Inside, with air conditioning. In the fall and winter, people come in heavy with Seasonal Affective Disorder symptoms. The short days and cold, long nights weigh their spirits, zap their energy.

My sister and I share a kind of euphoric mirror to this syndrome. If it rains in the heart of July from first thing in the morning through the day, we awake elated and hopeful. That type of day back home meant blanket forts and coloring books. That day, we were just kids, giddy with play and respite. Outside, the fields drank the rain. The tomatoes swelled and pinkened, waiting our return.

Michelle Castleberry’s writing has appeared in publications including Still: the Journal, EcoTheo Review, The Anthology of Southern Poetry: Vol. V – Georgia, Freezeray, Flycatcher, and the Mid/South Sonnets anthology. Her first book Dissecting the Angel and Other Poems was selected as a finalist in poetry for the 50th annual Georgia Author of the Year award. She lives and works in northeast Georgia as a clinical social worker and writer. She is currently working on her MFA with the Sewanee School of Letters in Tennessee.

Photos courtesy of the author.