In his thirty years of work in publishing, my grandfather never once revealed to his colleagues he was gay. Doing so could have cost him his job as a children’s book editor at a prestigious house, or at the very least, his reputation as an honest, hard-working family man. It took me only ten minutes, in a phone interview with the same publishing house, to accidentally out him.

The phone call had gone well so far. I sensed I was one question away from snagging the summer internship I’d been dreaming of all year. Suddenly, the woman on the other end of the call threw me a curveball.

“So, besides publishing-related activities and internships you’ve done, what else do you do for fun?”

I scrambled to present myself as a person with varied interests. (Do I have any extracurriculars besides literary internships? I can’t very well say ‘hang out with friends,’ can I?). Panicking, I latched onto a topic only slightly divergent from publishing.

“Well, I’m trying to write a novella for my senior thesis,” I blurted. “It’s about my grandparents, who were both gay in the 1950s. They got married because they wanted children, and of course to protect my grandfather’s career as an editor at—,” the name slipped past my teeth before I could stop myself.

Luckily, the woman on the phone found this historical tidbit fascinating, and jumped at the opportunity to talk about balancing a job in publishing with a writing career. Still, I couldn’t quite shake the feeling that I’d done something wrong. After hanging up with one last “Thank you again for your time,” I rested my head on the desk in front of me.

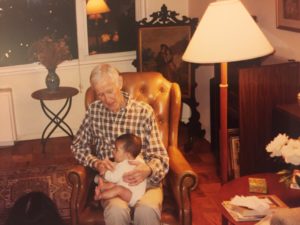

What authority did I have to tell that long-held secret? My grandfather died of cancer when I was one year old. I only found out about my grandparents’ sexualities at the age of eighteen, when I came out to my mother as queer and she revealed the family secret. Since then, I’ve oscillated between curiosity about their lives, and anger at my parents for not telling me sooner. That curiosity was part of the reason I chose to write about my grandparents, and why I decided to apply for an internship at that specific publishing house.

The day after the interview, HR called to offer me the job. And just like that, I was off to spend the summer in Manhattan, the city where my grandparents met, married, and raised their children. The city where I spent every holiday as a child, unaware of the unknown truth hidden throughout all those Easter egg hunts and turkey carvings.

This summer in the city will be different, I told myself. This time I will go in with eyes wide open, with the responsibilities of not only doing well in my internship and beginning work on my thesis, but also of better understanding my grandparents: the people I know so much and so little about.

My first weekend in Brooklyn, I ate dinner at my aunt’s apartment in Park Slope, where she and my mother grew up. I sat sandwiched between her two eight-year-old daughters and across from her twelve-year-old son. As the girls fought loudly over who deserved the larger portion of pasta, I fielded the expected questions about my summer: yes, the apartment I was subletting was safe and comfortable—only one cockroach sighting so far. Yes, I liked my publishing internship a lot. No, I was still not sure when my mother was planning to visit.

“Are you doing any sort of senior capstone project next year?” my aunt asked, waving at my cousin to eat the broccoli on her plate.

After a long pause, I cleared my throat. “Yes. I’m trying to write a novella, actually.”

“And what’s it going to be about?” she asked, nudging my cousin’s elbow off the table.

“It’s about New York in the 1950s,” I said carefully.

“Oh yes, I remember now. Your mother mentioned it to me.” My aunt put down her napkin and looked me in the eyes. “You’re writing about our parents, aren’t you?”

I nodded. From my aunt’s expression, I could tell that she had not told any of my cousins about our grandparents’ sexualities or their peculiar marriage, and that she was grateful I had kept my description of the novella brief. Around the dinner table, the hullabaloo of picking what to eat for dessert changed the subject for us. I think we were both relieved.

On my walk home later that night, a prickling feeling grew in my stomach. So she hadn’t told my cousins. The girls were probably too young to fully understand, but surely my nearly-teenage cousin could handle it. He already had a middle school girlfriend. How long would my aunt wait to tell him? Would she ever? I thought about how knowing my grandparents’ secret might have changed my own teenage years—how coming out to my parents felt like stepping into untravelled and uncharted land. Might it have felt the slightest bit more familiar?

The 5th Avenue stores were closing for the day. I watched as grocers rolled down their rusted gates and wondered what the neighborhood looked like when my grandparents raised my mother and aunt here. Different stores, I thought to myself as I imagined the gourmet frozen yogurt shop replaced by an ice cream parlor, with chrome-accented Cadillacs parked outside instead of Teslas. So much about the world had changed, and yet I still sensed my family’s discomfort with discussing my grandparents’ queerness. I was still expected to keep their secret.

The next day at work, I found it hard to concentrate on the stack of picture books on my desk until a ding prompted me to check my email. My boss had sent me a contemporary young adult manuscript that the imprint had recently acquired. I was to read it and give my thoughts for the next round of edits. Scrolling casually through the document, phrases jumped out at me: “queer,” “non-binary,” “homophobia.” I scrolled back to the top of the document to begin again. This time, I read intently. I gulped down every word.

By the end of the day, I had accomplished very little on my other projects but finished the novel in one sitting. It was a good draft, with dynamic characters and a well-paced plot. What I could not quite wrap my head around was the casualness with which the author described her young queer characters. There they were on the page: falling in love and making mistakes like all teenagers do. The next morning, I arrived at work a little early so I could read it again and write down some notes.

After a few weeks, I felt brave enough to visit the spot in New York I was most excited and nervous about: the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens. We last came here when I was in sixth grade. “Your grandparents wanted their remains to be scattered here in the Rose Garden, where they often walked together,” my mother had said as we entered the park, looking carefully into my eyes to make sure I understood. “What we’re doing isn’t exactly legal, so I need you to be the lookout while we reunite grandma and grandpa.” We had scattered his ashes when I was a toddler—too young to remember anything.

I accepted my role wholeheartedly, flushed with importance as I pressed my back against the white trellis and watched for park volunteers in dark green polo shirts. It was springtime, when the naked rosebush branches still shivered in the blustery air.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw my mother and aunt kneel by a “Cadenza” rosebush and empty the contents of a small plastic bag. It seemed impossible to connect the small cloud of grey powder with the woman who sat next to me only a few months ago, demonstrating her lengthy morning makeup routine. I had always been transfixed by the process, and by the prospect of one day applying my own makeup, and becoming a real woman like her. The ashes settled onto the hardened earth and I refocused my gaze to my assigned task.

Nine years later, I enter the park armed with my thesis notebook, a pencil, and a large tube of sunscreen. For a few weeks I’ve been trying to write a scene where my grandparents spend an afternoon in the park together, but it just hasn’t been coming together. I drop my bag under a particularly shady cherry blossom tree and imagine my grandparents sitting across the field in 1953, talking about a picture book my grandfather is editing. Soon I am picturing myself sitting with them and describing the YA book I am currently working on. In my head, they go bug-eyed when I get to the part where the protagonist yells at her mother for acting awkward around a gay friend.

I find myself thinking of all the things I wish I could ask them, like who exactly proposed their bizarre marriage situation, and what, if anything, they wish they had done differently. Next come the things I wish I could tell them: my doubts about pursuing a career in publishing for instance, and how recently I’ve been wearing one of Grandma’s silk scarves as a bandana. I stay there, rooted under the cherry blossom tree, until the sun is beginning to set and there are tear marks splattered on my journal. I still haven’t written anything, and it’s getting close to dinner.

On my way toward the exit, I decide to take a detour through the rose garden. There are fewer visitors in the park now, and even most of the volunteers have gone home for the day. I wander down the brick aisles, swinging my black tote back and forth so it bumps gently against my shins. About two-thirds of the way through the garden, I spot the bright fuchsia petals. The “Cadenza” wasn’t in bloom when we scattered my grandmother’s ashes, but I know that shade from the many times I’ve looked up the rose variety on the internet. Today, the plant climbs all the way up its trellis, and hangs low with flowers that brush my head when I walk underneath.

I reach up to touch one of the petals ever so gently. I’ve never felt something so fragile between my fingertips and am afraid I will break it. I pull back and start to move toward the exit. But after a couple paces, I pause. Around me, the garden is completely still except for the fluttering of branches in the evening breeze. In one smooth motion, I turn back around and pluck a rose from its stem. It falls neatly into my hands and I shove it into my tote bag. The green-vested volunteers remain preoccupied with their closing duties as I walk toward the park’s nearest exit.

Later that evening, I place the slightly wilted rose inside a book snatched from one of my office’s many “take shelves”—by far the best perk of the internship. I lower the book’s cover over the rose and begin to stack other titles on top of it, remembering the first time I saw a pressed flower on a dusty shelf in my grandparents’ old apartment.

“It’s really stayed preserved like this for years?” I asked my grandmother, stroking the tulip’s crepe-papery petals.

“Since your grandfather and I moved here, so before you were born,” my grandmother answered, placing a hand on my shoulder.

I continue placing books on top of the Cadenza until the stack reaches my thigh. I imagine the sheer weight of all those words pressing down onto the flower until it flattens and dries into a state it can remain in for decades to come. Satisfied with my handiwork, I crawl over to the sofa and pull out my notebook from my bag. Flipping to a clean white sheet, I pause briefly, and wait for the preservation process to begin.

Isabel Meyers is the Thomas E. Wood ’61 Fellow at The Common.