Poems by HUMBERTO AK’ABAL

Translated by LOREN GOODMAN

Table of Contents

- Holes

- Courage

- Love

- Mirror

- Stone bread

- We sow

- Mrs. Wara’t

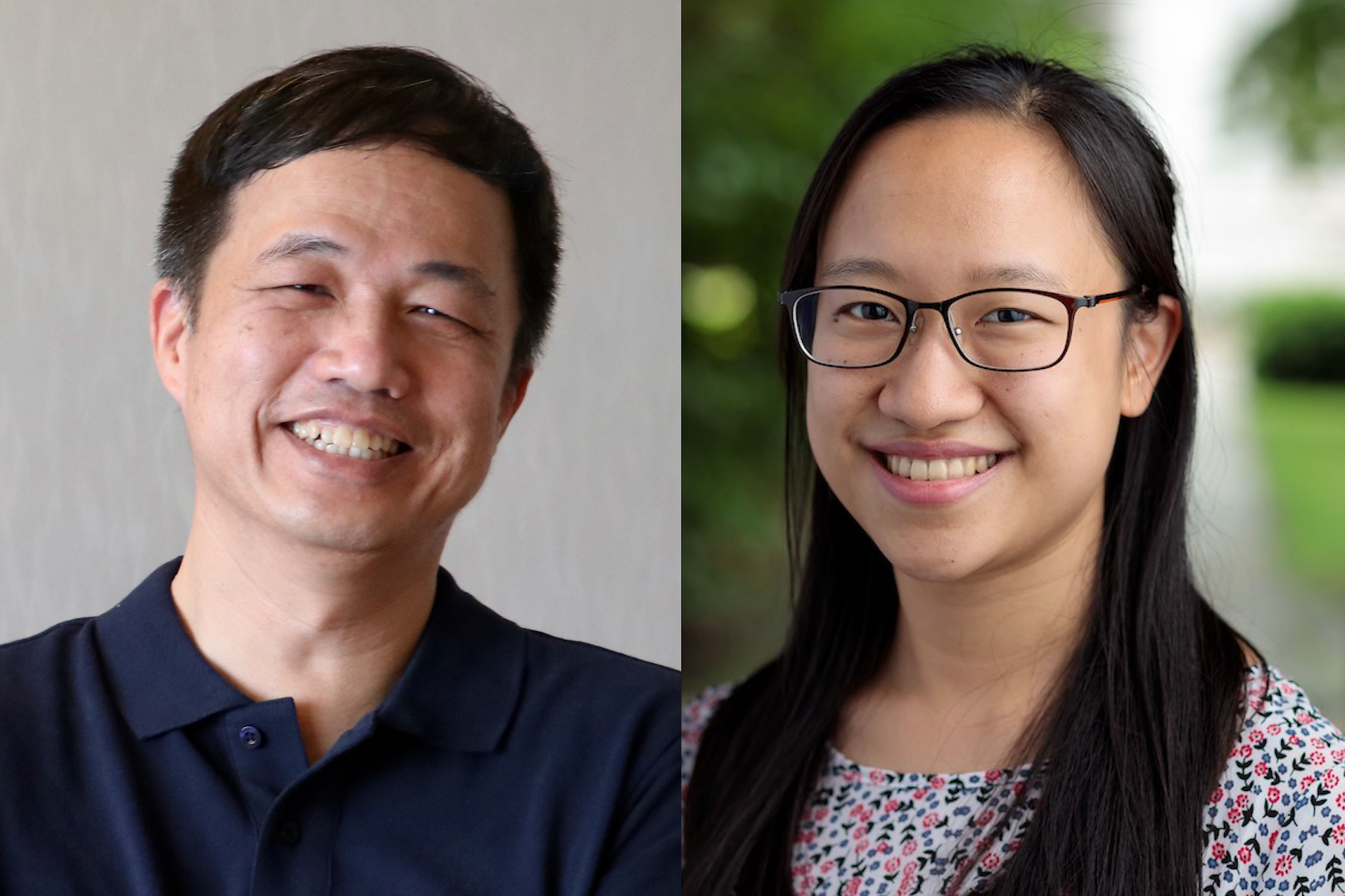

Humberto Ak’abal (1952 – 2019), a poet of K’iche’ Maya ethnicity, was born in Momostenango, Guatemala. One of the most well-known Guatemalan poets in Europe and South America, his works have been translated into French, English, German, Italian, Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic, Japanese, Scottish, Hungarian and Estonian. The author of over twenty books of poetry and several other collections of short stories and essays, Ak’abal received numerous awards and honors, including the Golden Quetzal granted by the Association of Guatemalan Journalists in 1993, and the International Blaise Cendrars Prize for Poetry from Switzerland in 1997. In 2005 he was named Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Ministry of Culture, and in 2006 was the recipient of a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

Loren Goodman was born in Kansas and studied in New York, Tucson, Buffalo, and Kobe. He is the author of Famous Americans, selected by W.S. Merwin for the 2002 Yale Series of Younger Poets, and Non-Existent Facts (otata’s bookshelf, 2018), as well as the chapbooks Suppository Writing (The Chuckwagon, 2008), New Products (Proper Tales Press, 2010) and, with Pirooz Kalayeh, Shitting on Elves & Other Poems (New Michigan Press, 2020). A Professor of creative writing and English literature at Yonsei University/Underwood International College in Seoul, Korea, he serves as the Chair of Comparative Literature and Culture and Creative Writing Director.