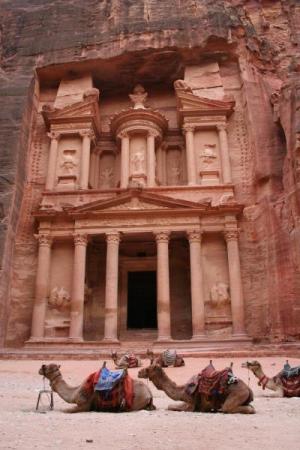

Photo taken by Graham Racher, from Wikipedia Creative Commons

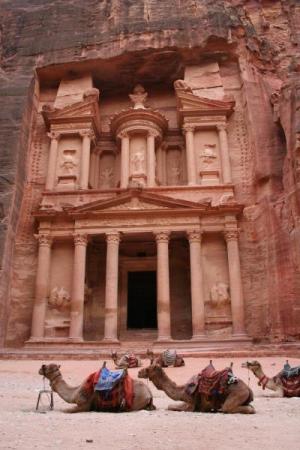

Photo taken by Graham Racher, from Wikipedia Creative Commons

Burckhardt, charged with finding the source of the Niger River by the African Association, set off in 1809 and traveled through Syria, Palestine, and Arabia for three years before detouring to Petra in August of 1812, where he determined to locate the rumored ruins of an awesome treasury. As cover, he wore Arabic dress, spoke the language, and declared the purpose of his journey the sacrifice of a goat at the Jebel Haroun, traditionally known as the tomb of the prophet Aaron, brother of Moses.

After Burckhardt died of food poisoning in Cairo in 1817, his papers were donated to Cambridge University, who recently spotlighted this collection. In his published travel diary, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land, Burckhardt writes of Petra:

I was without protection in the midst of a desert where no traveller has ever before been seen; and a close examination … would have exited suspicions that I was a magician in search of treasures.

Most widely glorified as the holding place of The Holy Grail in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Al Khazneh, or the Treasury, of Petra, is still gorgeously preserved and visited in high numbers, as evidenced by this YouTube video of cute cats in the old city and this slicker Japanese video of a walk past the strikingly carved buildings and through narrow streets just wide enough for a camel.

Elsewhere, modern-day Jordan is rapidly erasing its past, writes native writer Hisham Bustani in his short story “Nightmares of the City,” originally printed in The Saint Ann’s Review and republished online at Arabic Literature (in English). Bustani’s story skewers and bemoans Abdali, Amman’s “new downtown”:

Welcome to the new Downtown of Amman.

Behind the giant colorful billboards that fence the area with illusions of the future, there is nothing but dust, cranes, holes and workers shipped in from faraway countries, their sweat rung out of them without consequence.

Under a burning sun that slaps the flat ground stripped of its trees, people, and memories, a beautiful girl- scorched by the yellow rays- is running terrified in no specific direction as if someone is chasing her. She suddenly stops to say: “This is where the building used to be” then runs again and once more stops: “No, this is where the building used to be.” She runs, and runs, and runs. This is where the building used to be, no it was here, no here.

Bustani and his translator Thoraya El-Reyyes talk about rendering the story from Arabic into English in a lively exchange with ArabLit founder M. Lynx Qualey. About Bustani’s straightforward literary style, El-Reyyes says:

I was lucky with Hisham’s work because he doesn’t use the flowery prose that so many Arabic writers use. This flowery prose may read well to an Arabic reader, but it is difficult to translate this style into English without it sounding cheesy. Actually, I think the whole concept of “cheesiness” doesn’t really exist in Arab culture — it is practically impossible to even translate the word cheesy.

Photo from the When Monaliza Smiled Facebook page

Photo from the When Monaliza Smiled Facebook page

Marking a big jump forward in the Jordanian film industry this summer is the new release When Monaliza Smiled (Lamma Dehket Monaliza), a romantic comedy about a young single Jordanian woman seeking to escape suffocating expectations by securing an office job, where she falls in love with a low-status Egyptian coworker. Directed by Fadi Haddad and produced by Nadia Eliewat, the movie weaves in moments from classic black and white Egyptian films. Shot in four weeks with just $170,000, most of which came from the Royal Film Commission of Jordan, the film’s depictions of Amman are vibrantly sensory. In a review for Jordanian website 7iber.com (the name comes from the Arabic word for “ink”; the numeral 7 represents the word’s first letter “haa”), Naseem Tarawnah writes:

We get to see characters climbing the spiraling steps that line the hills of the Capital, women dodging glances of neighbors, the tiny eateries tucked away mid-stairway, and the abandoned old cinemas of Amman. At one point, Monaliza and Hamdi take a bus ride through west Amman, starring wide-eyed at the neon lights of cafes filled with the affluent; a stark contrast to their more immediate surroundings.

In less auspicious recent news, Jordan’s King Abdullah last week put his royal seal on an amendment to the country’s press and publications law that requires websites to register and obtain a license and makes website owners responsible for readers’ comments, according to Global Voices Online. In protest, many websites went black on August 29, and some protestors carried a mock coffin through the streets of Amman on September 12.

From Petra to Amman to cyberspace, Jordan reveals, writes, films, reads, watches, listens, and walks the streets in protest and for pleasure.

Jennifer Acker is the Editor of The Common and is a Faculty Fellow at NYU Abu Dhabi in 2012-13.