Curated by ELLY HONG

Here at The Common, our incisive volunteer readers are the first to review fiction and nonfiction submissions to the magazine. In this month’s round of Friday Reads, they recommend three exciting new works of speculative fiction.

Recommendations: How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu, Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir, and The Labyrinth by Simon Stålenhag

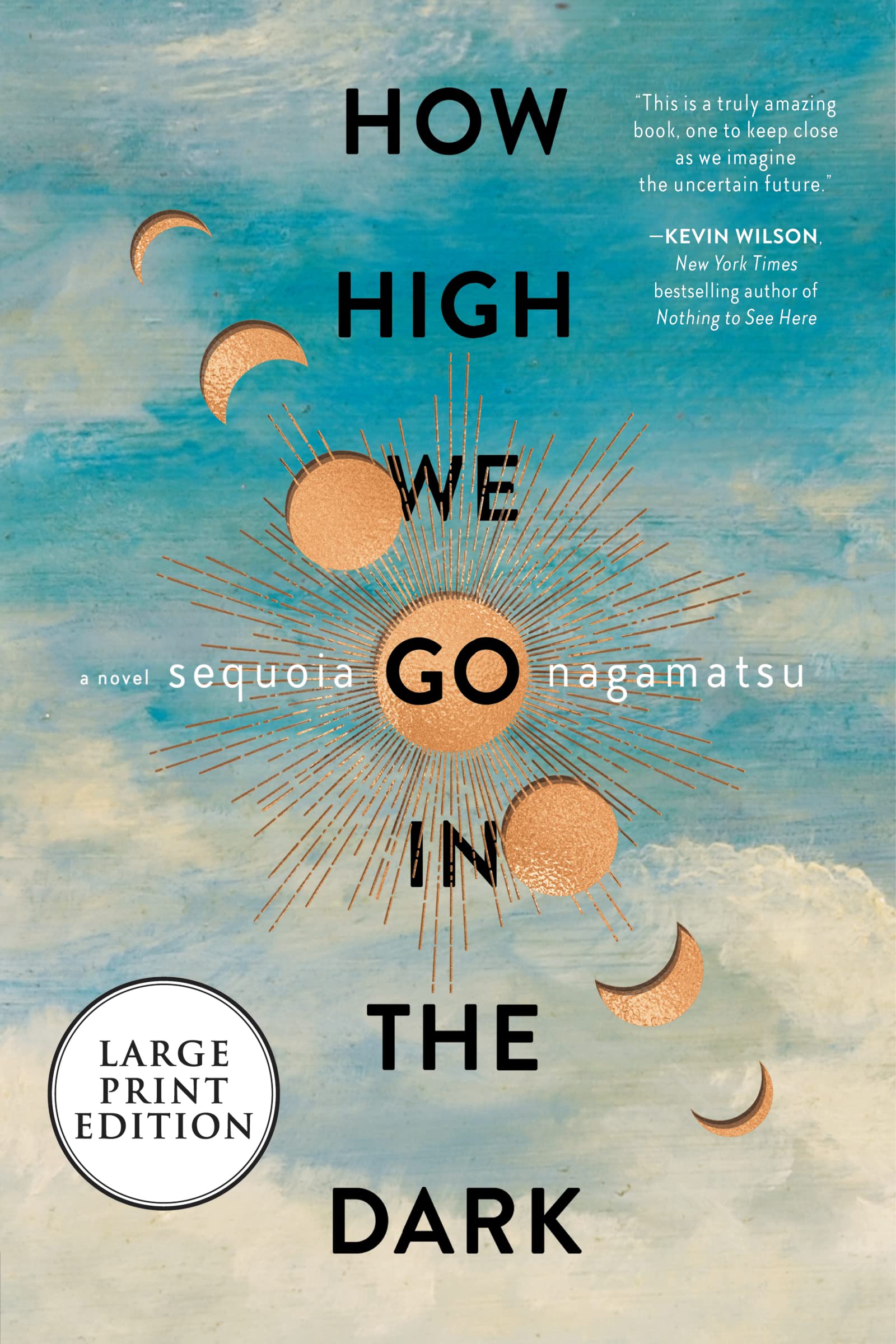

Sequoia Nagamatsu’s How High We Go in the Dark; recommended by Natasha Ayaz (volunteer reader)

I read How High We Go in The Dark by the water in Aruba, in a state of ceaseless cognitive dissonance. This breathtaking novel maps a sweeping cartography of human suffering and endurance, crystallizing around the collapse of civilization after an ancient plague is unleashed via Siberian permafrost. Admittedly, there were initial moments when I doubted whether this book was the appropriate choice for the tropical landscape—as I attempted a beachside detox from two years (and counting) of my own pandemic routine—but, in fact, the setting enhanced my reading experience. The blues of the Aruban vista reminded me of the sheer beauty of the natural world, all of which is precious, ephemeral, and at stake in both the novel and our increasingly troubling reality. I would read a story about, say, an amusement park for child euthanasia or a father struggling to complete his daughter’s world-saving climate research—and then look toward the sea and feel gripped with desperate love for all that we now have that we may not ten, twenty, thirty years from now.

Climate terror aside, it’s a rare thing to find a novel in stories so infinite in scope and so painstakingly, poetically linked. In How High We Go in The Dark, Sequoia Nagamatsu presents a constellation of voices in a universe of wonder. He intricately imagines the most harrowing potential futures of our world as we hurtle toward climate disaster and capitalist nightmare, but with such resolute tenderness that the ensuing pain is not only tolerable, but alchemized into hope. He charts the course of life on Earth from the first aquatic lifeform’s prehistoric emergence to the dawn of intergalactic civilization, guiding readers on a journey that shatters the heart and defies the time-space continuum.

Nagamatsu’s imagination is inestimable, and this book possesses a fatidic awareness, warning us of the dire consequences of our ongoing actions. It is equal parts cautionary tale and spiritual affirmation, leaving readers in awe of the vital, unseen threads that course through every living thing. The future is terribly uncertain, but love is relentless. We will never be alone.

Andy Weir’s Project Hail Mary; recommended by Heather Brennan (volunteer reader)

As someone who has found it difficult to read novels involving apocalyptic threats during the pandemic, I still thoroughly enjoyed Project Hail Mary. When an alien organism that consumes light suddenly infects our solar system’s sun, a coalition of world governments recruits a middle school science teacher named Ryland Grace to help analyze the new organism (named Astrophage) and generate potential solutions before Earth is plunged into a new ice age. Grace, a former molecular biologist, unwittingly becomes the world’s foremost expert on Astrophage and helps assemble a team of astronauts to travel to a nearby star that might be the key to Earth’s salvation. The book begins as Grace wakes up on the starship he helped to design with absolutely no memory of what he is doing there or where he is going. He is alone, the two other crew members apparently unable to survive the time spent in a coma. He must figure out his past and develop a plan for the future that will both save the planet and rescue him from what appears to be a suicide mission.

Weir’s style of science fiction is both accurate and inclusive, imagining awe-inspiring scientific discoveries supported by plausible math and logic that the average reader can follow. Grace is a capable and witty narrator, and he walks the reader through his thought processes as he navigates unforeseen crises and comes to terms with his own flaws as his memory returns. For fans of The Martian’s wry humor and attention to detail, Project Hail Mary is an energetic dive back into problem-solving and collaboration in the face of catastrophic failure. Anyone looking for space exploration, extraterrestrials, and unlikely friendships will find this book an instant hit.

Simon Stålenhag’s The Labyrinth; recommended by Samuel Jensen (volunteer reader)

For me, it’s a rare thing to finish a book and then immediately start it over again. A month ago I did this with Simon Stålenhag’s The Labyrinth. The latest in the artist, musician, and writer’s bibliography of what one might call literary sci-fi picture books for adults, The Labyrinth tells the story of Sigrid and Matt, siblings who travel on a routine science mission to the Earth’s surface from Kungshall, their secured, underground facility of survivors. In tow is Charlie, a teenager whom the siblings adopted during Kungshall’s messy, violent founding. The surface itself is a ruin, strange black globes wrapping all in a destroying miasma. From the ashes, enormous, striped alien fauna grows.

Stålenhag is well known for his signature art style, which places surreal technology or entities in otherwise utterly domestic tableaus often informed by details from Stålenhag’s childhood in eighties and nineties Sweden. The art of The Labyrinth tends more sci-fi overall, but if you followed Stålenhag on socials as he worked on the book, you would have seen careful preliminary paintings of very specific chairs, thermoses, and other objects that, in the book itself, have huge spreads dedicated to them. (My special favorite of these is of a certain handset phone.) In the moment, we wonder: why dedicate pages and ink to such mundane objects only? But this is The Labyrinth’s exact genius. It is a book about comings and goings, a book that, as Sigrid and Matt leave on, then return from, sample-gathering expeditions, plays with sequences of like images that progress or repeat as the siblings’ conversations circle the book’s dark heart. The book encloses and then, suddenly, opens.

The reason I started The Labyrinth again right after finishing was to flip back and forth between these sequences. Not exactly to look for things hidden, but just to look, knowing what I then knew. In a science-fiction world, Stålenhag’s focused domesticity becomes a kind of ghost-in-reverse of the things that will happen to these objects, in these spaces and to the people in them. I don’t want to say too much, but there are a few sequences featuring the characters themselves that I will not soon forget.

The glue to all this visual work is The Labyrinth’s prose, which is spare and matter of fact in the voice of its narrator, Sigrid. The writing is beautiful in its own right, and essential context for the images. Reading the siblings talk about Charlie while looking at the paintings of them walking around in their cabled suits, the experience is like listening to a radio while watching archive footage from the future. The stuff on the radio is bleak, even frightening, but you can’t stop listening.