There’s a cafe called Dante’s on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village that my father and I used to visit when I was a teenager.

It’s located in what is sometimes called the “south village,” which once was largely Italian. There were still traces of that neighborhood when I was a kid. Grandmothers on folding chairs outside tenements on Leroy Street, Our Lady of Pompei on Carmine Street, a Mafia social club on Sullivan Street, St. Anthony’s Church, the Vesuvio Bakery, tough kids hanging out in Thompson Park, Ottamanelli’s butcher shop.

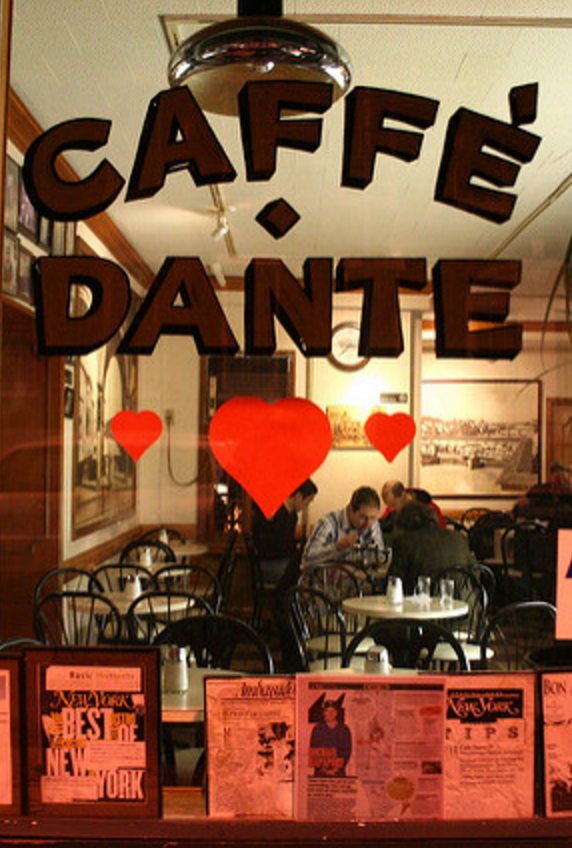

In 1978 Dante’s still had an old-time neighborhood ambiance. It was a small place with white circular tables and florescent lights along the ceiling. There were pastries, but mostly people went there to drink coffee and talk. If the weather was good, you could sit outside on wobbly chairs facing the street.

The waitresses of Dante’s were friendly, but not too friendly. Busy, but not too busy. Pretty, but not too pretty. They weren’t necessarily Italian, but nearly all were from some foreign land and spoke with hard-to-place beguiling accents. I don’t know if it’s true, but someone once told me that several of them were from the island of Malta. There was something that seemed especially worldly about those young and not-so-young women. Maybe it had to do with some of them coming from an island that had seen waves of migrations–Sicilians, Greeks, Romans, Phoenicians, Arabs, Spanish, French, and the British, not to mention the Knights of Malta. Or maybe when you’re a teenager anyone with an exotic foreign accent seems worldly. Wherever the Dante’s waitresses may have come from, just the hint of a smile from the right one could make your day.

My father, who taught English at the College of Staten Island, was also hard to place. If you saw him on the street, you might have guessed he was from the Indian subcontinent. He’d grown up in Jewish Boston in the 1930s, and there were faint traces of that city and his immigrant parents in his accent. Friends he’d had as a kid and still kept up with had names like Herbie, Sid, and Lenny. During World War II, my father had gone AWOL in San Antonio and spent his time in the Mexican quarters of the city where he blended in easily. When my mother was in labor in 1960 at a Washington Heights hospital, he’d left the waiting room and gone out for a drink and a bartender who refused to serve him told him, “We don’t serve coloreds here.” A Sicilian, living on Elizabeth Street, just a few blocks from Dante’s, probably would have thought my father was Italian.

It was a spring afternoon on the day I remember, just warm enough to pass some time at one of Dante’s tables on the street. My father and I were sitting outside with our espressos. Directly across the narrow street was a series of brightly painted 19th century townhouses. From 1966-to-1968 Bob Dylan had lived in the one at 92 MacDougal. Just up the block was a Mexican restaurant called Panchito’s owned by my dad’s friend Bob Engelhardt whom we’d seen on our way over to Dante’s that day. Back in the ’60s, Panchito’s had been the Fat Black Pussycat where Dylan supposedly wrote “Blowing in the Wind.” Mr. Englehardt told me he doubted this was true, and that in any case the Fat Black Pussycat had been a cesspool.

We were drinking our coffee, and I was getting some ineffectual fatherly advice about school and girls, before we somehow got on to Passover and the question of god killing the entire first born of Egypt. My father suggested that God was a pretty nasty fellow back then and mentioned other examples of his hot tempered and vindictive behavior.

There was a studious looking young man scribbling away on a yellow legal pad at the table to our left and three middle aged men at the table to our right. One of those men was wearing a leather jacket. He had black slicked back hair. Without meaning to do so, I began listening to the conversation he was having with the two guys sitting at his table.

“Throw him off the roof. That’s what you gotta’ do,” one of the men was saying quietly.

My father at this point was telling me something not especially interesting about the Boston Red Sox outfielder Carl Yastrzemski.

“Make it look like an accident. Like what happened with Tommy.” That was what I heard quite distinctly from the table at my right. I glanced over without trying to be too obvious about it. These were hard looking men about the same age as my father.

For the next few minutes, as we sat and sipped on our second espressos, the men’s mumbled conversation drifted in and out of my range of hearing. We were waiting for the check, and the men at the next table had gotten up to leave when the one in the leather jacket looked at us and walked over to our table.

“Eddie,” he said looking at my father.

“Sammy? Sammy. How the hell are you?” my dad said.

The two of them shook hands, two middle aged men with big dopey smiles, grinning at each other.

“Great to see you, Eddie,” the man in the leather jacket said, before heading down the street with his two companions.

“Who was that?” I asked, after the three men were halfway down the block.

“Oh. That’s Sammy the rat,” my dad said.

“How do you know him?”

“From Bill’s Grill. The bars on Christopher Street. The White Horse too. Sammy was working on the docks back then. Lots of longshoremen in those bars. Plenty of stuff coming off those boats ended up being held for safekeeping by the bartenders.”

“He and his friends were talking about throwing someone off the roof,” I said.

“Sammy’s a good guy. Someone once wrote something stupid about my first book. A bad review. Sammy wanted to track the guy down and set him straight.”

“That’s supposed to convince me about how good he is?”

“Not about how good he is. About how he’s a good guy. He was friendly with the Catholic Worker guys too. Ed Egan. Michael Harrington. You’ve met them. They’ve been up to the apartment.”

“Sammy the rat hasn’t been up to the apartment.”

“Working on those docks, it was a hard life. He wasn’t a big shot. That’s all gone now. It’s a different city now.”

We didn’t talk for a couple of minutes and then my father said, “Don’t worry about what you think you might have heard. Sammy the rat is a good guy.”

In 2015 after 100 years of operation, Caffe Dante was shuttered and the storefront was sold to an Australian restaurant group. When the new place opened, it kept the name Dante, but the humble interior had been renovated with cream colored banquettes, and a new menu featured cocktails with names like Chamomile Sazerac and Spiced Pear Bellini. My father was right. It’s a different city now.

Jacob Margolies is a journalist working out of the New York Bureau of The Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest newspaper. He’s recently had literary pieces published in The Forge Literary Magazine, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Project Syndicate, The Summerset Review, Full Grown People, and Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood. He is also the author of The Negro Leagues: The Story of Black Baseball (Franklin Watts).

Photo by Flickr Creative Commons user dotpolka.