By AKWE AMOSU

When the storm’s coming, you can feel it. The atmosphere’s tense, quivering the leaves, hot, damp air close up to your face, the cloud doubling and darkening, metallic grey, sucking in the light. There’s a portent in the frenzy of birds and the cat’s retreat into the bottom of the clothes cupboard. Sometimes night falls and everything is still on edge, pending. The child loves to hear the thunder sneak up in the dark with a low growl. She counts the seconds after each cannonade. When the rain finally falls, you can’t hear much else, even when there’s shouting. She likes to climb out of bed into her window and get gooseflesh in the wind, then to jump back, shivering, under the covers to get warm. Then she does it again. Once there were hailstones, thrashing the asbestos roof. The noise obliterated everything, like a drug; she slept.

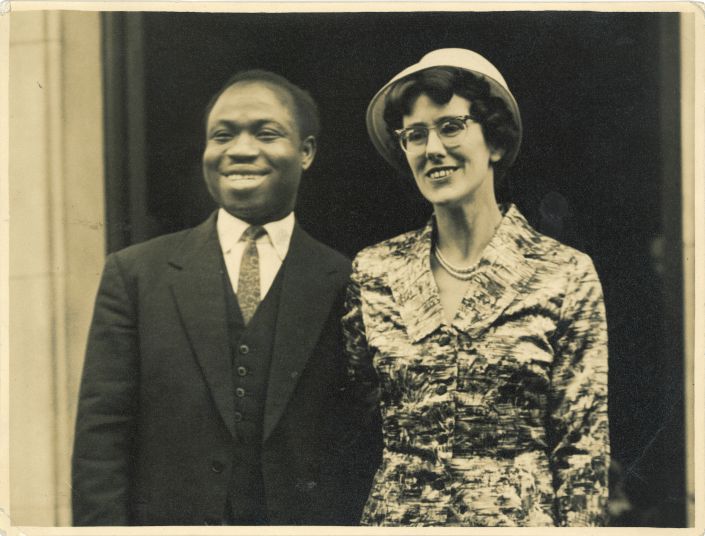

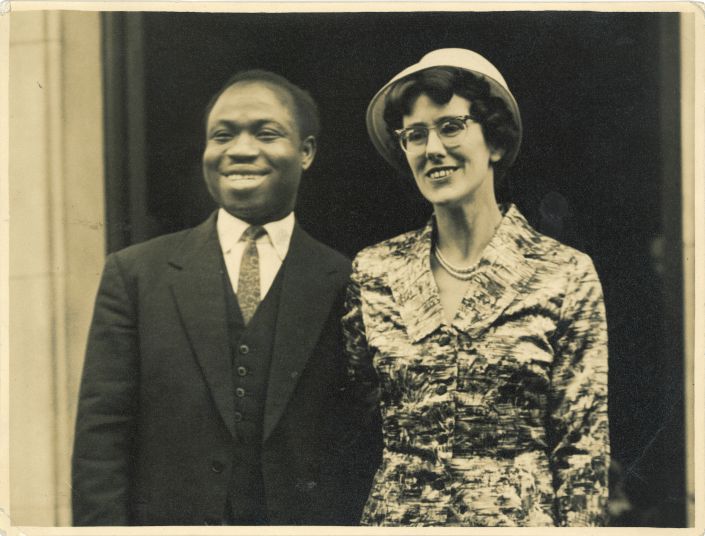

To Margaret, 1966

To Margaret, 1966

Hi Love!

Am taking advantage of John’s departure tomorrow for Lagos, en route, Freetown, to send you this. At least you’ll get it within 48 hours. First and foremost, we are all fine, and had some storm and rain this evening. It is a bit cool now, but for how long?

A had her school sports. She took part enthusiastically in all the events scheduled for her age group and won none, which of course upset her a bit. The climax—in the Father’s Race, a father fell at the finishing line, tripping her as she held my hand and she landed on him almost pulling me down with her. Only screams, no bruises, no bones broken and we went to see the agricultural show on the way home.

Mrs Udo has been marvelous with Gran’s insulin. Do send her a card. Ackers and I will also welcome one. Every time she asks me when you are due back and I say Saturday 26th, she says “Saturday? Goody!” and I try to say, “not this one!” but it doesn’t register.

Oh, I must tell you something—I love you.

Your own, Nunasu

The mother and father are angry that the Igbos have been vilified and forced to flee from the North, and now from the West. The university’s Igbo staff, even Vice-Chancellor Dike himself, have packed and moved abroad or fled home to the East after seeing tens of thousands of their people murdered in the North. The child listens closely to every dinnertime conversation. In the months before Christmas, Igbo friends drop by after dark: “Could you look after this until we return?” Books, pets, valuables, a car. “Yes, of course,” says the mother, and to the child: “Don’t mention this to anyone.”

… I returned to Nigeria in October to find that the large majority of the academic and administrative staff of Eastern origin had for reasons of personal security returned to the Eastern Region. Hundreds of Eastern students also left the campus. The continued and isolated killings of Easterners in Lagos and parts of the federation served to confirm the fears of the great majority that they can best find security within their own borders.… But the fundamental issue is not that of personal security. One must face the fact that since the events of recent months, Nigeria is bitterly and grievously split into regional groups, each deeply suspicious of the other.… Because of this, my position as Vice-Chancellor has become very difficult and I feel my usefulness is curtailed. It is this consideration which has really influenced my decision to resign.1

1. Extract from resignation letter of Vice-Chancellor Kenneth Dike

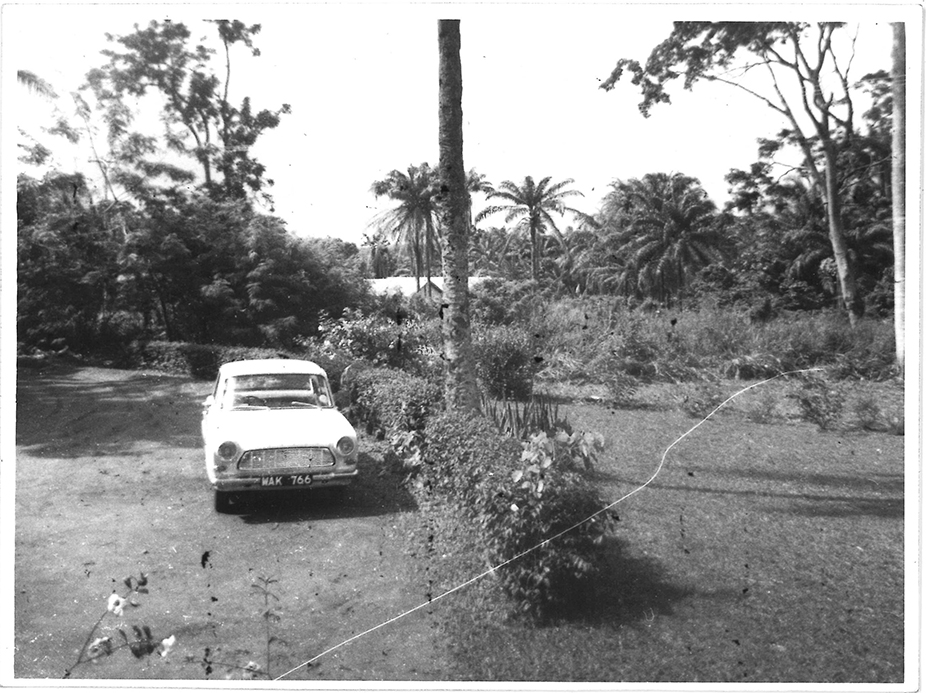

Open the shutter.

Sharp sunlight falls

into a forest clearing.

A group of adults

stand on a grass verge

beside an open car boot.

Coffee, biscuits, a cigarette,

legs being stretched, a break

from a hot, seven-hour drive.

Few other cars; the empty

Benin-Sapele road is straight,

rising, falling, southeastward.

Car, thermos, specs, all sport the

italic slope of late-’50s style. No

hurry. Quiet voices, a brief

laugh. Birdsong. Monkeys calling.

Alone at the front of the car,

the child squats barefoot

to examine huge butterflies pinned

to the grille by the rush of air:

purple and shimmering blue,

fire-orange. In a moment

she will beckon to her mother,

who will come, smiling, to see.

Close it.

It is the time before seatbelts. An only child can sit on the edge of the back seat, peering through the gap between the parents in front, telling them about school, what she wants for her birthday. That’s how it is when the mother puts her hand down to adjust the seat and pulls out a black chiffon scarf. The car suddenly floods with a dangerous gas. The father dissembles: he gave someone a lift—she must have dropped it as she got out. The mother’s voice is a razor through his fumbling tale. Cold, heavy disappointment seeps into the child’s bones. Another fight.

May 30, 1967

Having mandated me to proclaim on your behalf, and in your name, that Eastern Nigeria be a sovereign independent Republic, now, therefore, I, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, by virtue of the authority, and pursuant to the principles, recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of “The Republic of Biafra.”

To Nunasu, 1967

Outside the personal area, you and I can see that part of the hopelessness of the Nigerian situation has been the refusal of the people responsible to express genuine contrition for the crime against the Ibos; and that the war is making it a greater crime and became inevitable because of this initial lack of contrition. It is the same with us—until each of us has faced the hurts we have done each other and expressed our genuine regret and sorrow, we can go no further and, in fact, we do make things worse whenever we talk.

Margaret

It is early morning; time to eat cornflakes, to find homework, satchel, shoes, and run to school. From the veranda, the two of them watch the father only a few feet away, walking from the bottom of the steps to the car. Alfred leaps to pick up his suitcase and puts it in the boot. Your father is leaving us, is all she says, eyes blazing, voice twisted like wire. He doesn’t look back, gets into the car and drives away, leaving a black hole hovering over the garden, sucking in every possibility, their future. The child is confounded. What must she say? Should she go to school?

We were all three on the veranda, he was going down the steps, and in a mixture of anger and frustration and a final desperate hope that she might persuade him not to do so, I told her that he was leaving us. It was a cruel thing to do, and very wrong, a damaging psychological blow. She cried out in a terrible way and as I had delivered the blow and could do nothing to alter the situation, I could do nothing to comfort her.

I am taking Black Voices which is a joint present to us from Vaughan. I hope you don’t mind; if, however, you want it, I shall return it. I am also taking my Classics Club recording ofTchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto 1, having also taken my Frank Sinatra’s Point of No Return (birthday present from Gran). I feel no bitterness towards you, Margaret. I know I am ill, physically and emotionally, and that you can only make it worse. Try to understand.

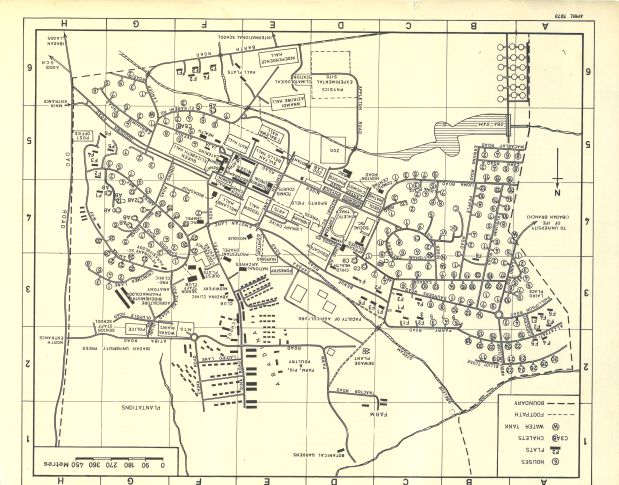

The child knows the campus. She goes where she likes, records every shortcut, stores out-of-sight places where no one could find her, in case of need. So long as no one asks questions, everything is fine, everything is normal. On the floor of the children’s section in the bookshop, she can’t be seen from the manager’s office. She is reading her way through every Puffin book, becoming a silent character roaming Mesopotamia, Nazi-controlled Greece, England’s Lake District, or America’s Deep South.

One day, some police come to the house to tell the mother she has been denounced for harboring Biafran property. She must go with them on suspicion of being an agent for the secessionists. The mother tells the child to stay at home, but she knows the police post—it is beside her school. She and her friend Roland take to their bikes, using the shortcut through Anatomy and Biochemistry, and ride back and forth outside the post, then sit on the grass verge to keep vigil while the mother is interrogated. What if her mother is held overnight—where will she sleep? Where should the child sleep? How will they talk to each other?

I beg you to come home or to tell me that you never intend to. This is not for my sake but for the child’s. She is getting more and more unhappy and difficult to manage. She is constantly disappearing from the house and today did not come home from school. Alfred and I began to look for her at 1.30pm and eventually found her at the L——’s house. She knows that she must not do this and that I shall be very angry. She cries in a broken- hearted fashion over it, yet keeps on inviting punishment by repeating it.

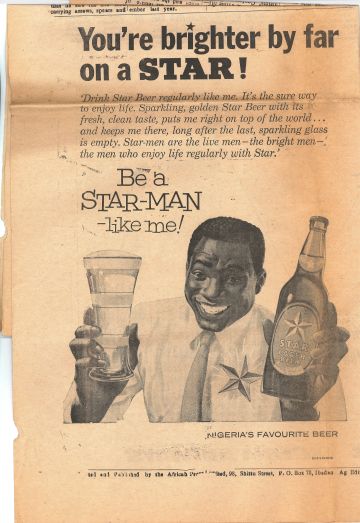

They zip up Crowther Lane, past the Club, turn right on Emotan Lane, left at Our Lady Seat of Wisdom, pass the bookshop, and left again onto Oduduwa dual carriageway. The child knows every gear change, the varying pitch of the engine’s song, and hums idly along. They turn out of the university gate onto the Oyo Road. A radio in the petrol station chants: “To keep Nigeria one is a task that must be done!” The child, in singsong mode, repeats it quietly a few times and then moves on to “Goody-Goody! Tha Pen-ny Sweet that’s Good to Eat!” Lustily now, she extols the father’s favorite beer: “You’re brighter by far on a Star!” until the mother asks her to sing a little more softly, perhaps a real song. A cooling breeze fills the faded windsock. They reach the railway crossing at the same time as cows leaving the airfield, the Fulani herder flailing rumps with his staff to hurry them over. As the last one reaches the other side, the alarm sounds and the gate comes down. “Oh, damn,” says the mother. It’s hot now that the car is still. The seat is sticking to the child’s legs. She wants a drink. The train passes, the gate lifts, they drive on through Bodija Housing Estate, past Standard Bank at Agodi and the leafy GRA,2 and finally in at the gate of the university hospital. Pride stirs the child; here is where people do good.

2. Government Residential Area

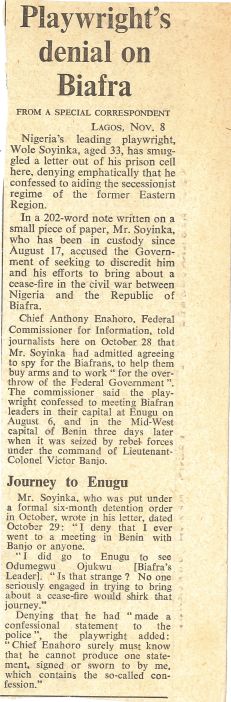

Mrs. Soyinka, who works at the medical library with the mother, is beautiful. The child wishes she could be in the Soyinka family. Sometimes she and the mother go to visit them on Ebrohimie Road and she reads Tintin books with the oldest son. Mr. Soyinka is in prison. His wife tells the mother the latest information, new problems with his health. They discuss a way to send him medication. The child knows Mr. Soyinka was trying to prevent the war but General Gowon didn’t trust him. She’s seen Mr. Soyinka driving around campus in the Theatre Arts Mini Moke, with its swaying dancer figure on the side. She knows about his play Kongi’s Harvest. She went to see it with the mother, even though it is not for children. It’s wrong for him to be locked up. She wishes she could help him get out. She leaves the mother and Mrs. Soyinka, and takes her book deep into the quiet stacks to sit on the cool floor. It’s better to have a father in jail than a father who left home.

Mrs. Soyinka, who works at the medical library with the mother, is beautiful. The child wishes she could be in the Soyinka family. Sometimes she and the mother go to visit them on Ebrohimie Road and she reads Tintin books with the oldest son. Mr. Soyinka is in prison. His wife tells the mother the latest information, new problems with his health. They discuss a way to send him medication. The child knows Mr. Soyinka was trying to prevent the war but General Gowon didn’t trust him. She’s seen Mr. Soyinka driving around campus in the Theatre Arts Mini Moke, with its swaying dancer figure on the side. She knows about his play Kongi’s Harvest. She went to see it with the mother, even though it is not for children. It’s wrong for him to be locked up. She wishes she could help him get out. She leaves the mother and Mrs. Soyinka, and takes her book deep into the quiet stacks to sit on the cool floor. It’s better to have a father in jail than a father who left home.

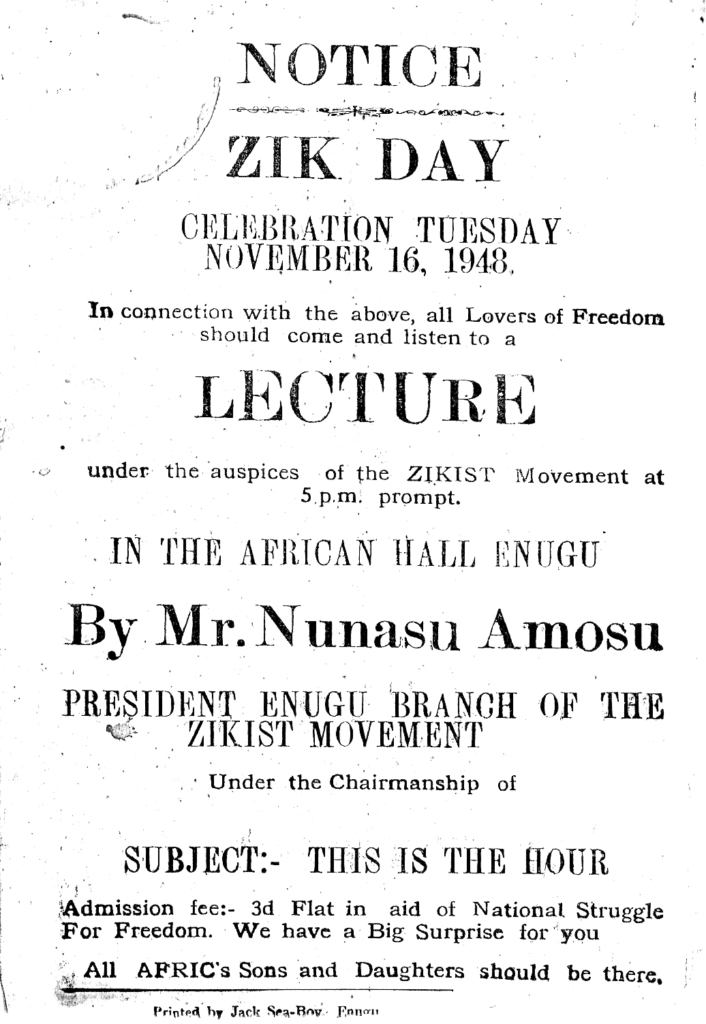

Nunasu Amosu was president of the [anti-colonial] Zikist Movement branch in Enugu … he organized a meeting for November 1948, at which he would give a speech entitled “Now is the Hour”. But the meeting was disrupted and he was prevented from giving the speech by the police. Amosu and his executive declared a “state of emergency” and called on their supporters to prepare for insurrection. …

The British rounded up Zikists throughout the country, tried them for sedition and other offences, and imprisoned them. Among those jailed were Mokwugo Okoye, Martin Onaiyekan, Francis Igioh, Jerome Oduko, Okei Achamba, Bob Ogbuagu and Nunasu Amosu, who was held in Kaduna.3

3. Ehiedu Emmanuel Goodluck Iweriebor, Radical Politics in Nigeria, 1945–1950:The Significance of the Zikist Movement (Zaria: Ahmadu Bello University Press, 1996).

It’s early but the mist is lifting.

She needs a weaver bird’s nest

for the nature table.

She knows where they like to build,

steps into the mesh of dew-filled webs

glimmering in the grass.

Inch-high nodular towers, the earthworms’

night sculptures, collapse underfoot,

cool between her toes.

She passes the oil palm to the left,

following along the jasmine hedge

until the cycad,

Turns right, circling the graceful tree

whose sap is as good as dish soap

for blowing bubbles.

Now she’s crossing rough ground,

plants her bare soles firmly, stepping

over the termites’ nest,

Skirts the thorns, reaches the Iroko,

lays her cheek against its pale bark,

and tips back,

Until her eye is looking a hundred

feet up its uninterrupted trunk,

into the canopy;

A million tailor ants march upward

in a fluid bronze column, inches

from her nose.

She wishes she could fly like a sunbird

up to the house, swing on the Thunbergia’s

mauve racemes to listen.

If she understood human language,

she might learn what the adults stop saying

when she appears.

Here’s a nest, woven sock of twigs;

inside, eggshell fragments,

soft down.

Nunasu, letter to the child, 1998

Your gift to W—— of a pedal bicycle reminded me of a telephone call in 1969 from Margaret informing me of your bicycle having been stolen from the garage, and that you missed the bike. I was so moved that I went out immediately to buy one and get accessories—bell, dynamo lamp and other “sporty items”. When I called that evening at Crowther Lane, you kissed and hugged me, but when I went round the back of the vehicle and brought down the bike, you were so surprised and enthralled that you jumped on it and, starting with the next door neighbours, you must have covered the whole campus, so that I was obliged to stay for supper. Do you remember?

The radiogram marks each day’s end

with the BBC’s pips for 6 o’clock,

then Lillibullero, a call-sign flung out

to all the empire’s children, with news

of the pounding storm in the east. But here,

far from the fighting, it heralds gin and tonic

as dusk enters every crevice. The first planet

edges up over the trees into a spangled heaven,

as London’s signal falls to our African earth,

a cold war star, like the satellites flickering

across the firmament, looking down on

our new freedom, on the civil war, on the men

who cut off the breasts of the nursemaid’s friend,

on the dead left lying in the dewy, night grass.

The child listens, a whorl of fireflies

perplexing her eyes.

The mother and child drive their friend, Red Cross doctor Cato Aall, to Lagos so he can catch a plane to Norway. By the time the plane has taken off, it is late. There is a curfew banning intercity travel after nightfall, but the mother does not want to stay at the Airport Hotel; she wants to go home. She tells the child they will set out; if they get stopped, the worst that can happen is that they will have to stay at the checkpoint until morning. Whenever the child hears the mother sounding certain, she feels doubt. The mother’s view of the world is unusual: she takes risks that others would avoid; she has strong views that upset people. The child wishes they were not leaving Lagos. The road is completely empty, except for the night flyers spiraling in the beam of the headlights. The child lies on her kapok mattress, gazing at the dome of stars wheeling away behind them. But they are soon flagged down by an angry soldier. Be quiet and let me do the talking, says the mother. Fluent, persuasive, overconfident, the mother talks him to an impasse, but he cannot yield. He orders her to pull over and park. As she does so, she tells the child to sleep, but the child cannot sleep; she is afraid. The mother seems unaware of the danger, the guns. Why can’t she be like other mothers? Let this end well, she pledges, and I will finish my arithmetic homework every day. An hour later, exasperated that the oyinbo woman seems ready to stay all night without fear, the soldier brusquely allows them to proceed. At the Ibadan checkpoint, the soldiers hear they were previously allowed to pass and let them in. The mother is triumphant.

He says he will take her to see his new house. She wants only that the two of them spend the day alone, but he is determined, so she agrees. He introduces a lady, but the child isn’t sure who she is; she’s called Aunty Funke. She seems to be in charge of the house. Everyone there seems to feel the child should remember who they are, but it is nearly two years since the father left, and the child can’t recall everyone’s name. They are surprised and disappointed. The father also seems sure that she will remember, and he too feels let down, leaping to help her out but always just too late, once she has been exposed. She’s failing. She’s counting the hours until the end of the memory tests, the questions about whether she can eat Nigerian food, speak Yoruba, knows the meaning of her name, likes school. She tries hard, she obliges, feigns regret at leaving as they get back into the car, but once back at home, her relief is enormous. Worse, she hardly got to talk with the father. Children there don’t seem to be able to speak with grown-ups, the way they can in her house.

Margaret, letter to lawyer, 1969

I feel very disturbed by this counter-claim of my husband’s, that the child be made a ward of court. I have never refused him access to the child. I have allowed her to visit his new establishment. When he wanted her to go again a few days later, she herself said that she didn’t want to go. He has made no attempt at all to see her since then, now more than two months ago…and I may say that neither he nor other members of the family come to see her except at long intervals.

Mr. Soyinka is home from jail. The mother and child visit with many others, clustering on the porch in welcome. His speaking is as resonant as singing, an enchantment. The child lurks in the rear, marveling at a mobile hanging nearby, a floating concatenation of poems spidering across toilet paper, written with instant coffee for ink. She imagines him in his cell alone, weighing the words, balancing the verses.

Lagos, Nigeria, January 14, 1970

I, Philip Effiong, do hereby declare: I give you not only my own personal assurances but also those of my fellow officers and colleagues and of the entire former Biafran people of our fullest cooperation and very sincere best wishes for the future. It is my sincere hope the lessons of the bitter struggle have been well learned by everybody and I would like therefore to take this opportunity to say that I, Maj. Gen. Philip Effiong, officer administering the government of the Republic of Biafra, now wish to make the following declaration: That we are firm, we are loyal Nigerian citizens and accept the authority of the federal military Government of Nigeria. That we accept the existing administrative and political structure of the Federation of Nigeria. That any future constitutional arrangement will be worked out by representatives of the people of Nigeria. That the Republic of Biafra hereby ceases to exist.

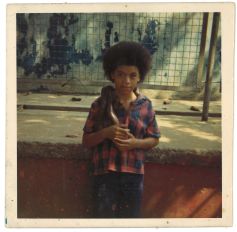

The child volunteers at the zoo. Mike gives her a piece of the small mammals’ salty boiled meat to chew and sets her a task—chopping fruit for the lemurs or mixing fortified milk for chimpanzees Zetta and Aiye. He doesn’t let her have anything to do with Haruna and Imade, the gorillas. She cannot bring herself to swing the white mice against a wall by their tails before they are dropped into the pit for the snakes to eat.

But when things are quiet, Mike pulls out a rainbow boa to drape around her neck; visitors exclaim and scatter, then edge back to look on in fascination. The snake is much stronger than she is. It is also dry, cool, smooth, and graceful, gliding into a sleeve, up around her neck, out of the collar, then winding down the other arm, in constant motion.

Akwe Amosu is a Nigerian/British poet based in New York. Her book, Not Goodbye, was published in South Africa in 2010. She was a featured poet at the Franschhoek Literary Festival in South Africa in 2014. She works full-time at the Open Society Foundations (OSF) as their regional director for Africa, traveling frequently in the continent. Before joining OSF, she worked as a journalist with the BBC, the Financial Times, and allAfrica.com, and with the United Nations in Ethiopia.