By BEN TAMBURRI

Photo courtesy of author

Baileys Harbor, WI

Baileys Harbor has always felt like a place that is eternally old, eternally in the past. It is a destination for quiet summers on the Wisconsin peninsula, where the insignia of range lights and lighthouses decorate the bathroom of every home, and Dala horses wreath the doors. It was the place of my youth, even if it was only for a week each year. As a kid, when my family visited, I felt at home among the retired condo-dwellers.

When I arrived alone last summer, the scent of my grandparents’ condo was heady. The smells of caramel-flavored coffee, sugary cereals we didn’t have at home, and the wooden drawers my grandparents hid treasures in coated every object in comfort and intimacy and burrowed into every sensation, glance, and texture.

I left the little luggage I brought with me in my grandparents’ bedroom and walked down the main street, unaccompanied, for the first time in my life. The evening sun gilded faded signs advertising vacancies and supper clubs. I had no plans but to exist in a different place, on my own for once. I wanted to have time and space to take things in, to breathe independence for a week: an escape to quietude and reflection before I started college in the fall.

I passed gold-stained hydrangeas, bergamot, and spider mums in the front garden of the Blacksmith Inn on my way to the marina, where my family took the same photo on the same bench every year. From here, I looked out at the lake and the boulder-lined dock that carves into it. Tomorrow I will hop from boulder to boulder to the end of the dock, as I always have, and I’ll remember my childhood fear of falling into the catch of spider webs and lake foam. Even this mild terror of twisted ankles, venomous spiders, and claustrophobia is an entry point to simpler times.

The beaches of Baileys Harbor are for birds, too pebbly and coarse to relax on. The water is cold, and the waves break at your ankles. Michael—my older brother—and I, before Will was old enough to swim and before Max entirely, were always too scared of the cold water and the beach was too itchy. Instead, we would run to the wet brown sand, warm and muddy, and grab a handful before the next wave rushed, chasing us back to the shore, where we would throw mudballs at the lake. It had been sixteen years since we played that game, but this was the memory that crashed again and again over the sand with constancy, overtaking all others. I imagined not only Michael and I slinging mud at the lake we had thought was an ocean but also some other kids, three and five, who had discovered the game for themselves. I thought that, seventy-five years ago, my grandmother and her siblings would have done the same thing, even though they did not come here until fifty years later. It was a pastime that seemed to lend itself to any kid on this beach, anyone too plump-limbed to avoid the scratch of the sand but not blubbered thickly enough to brave the bite of the water. Eternally, on the shores of Baileys Harbor, there will be kids slinging mud.

The Door County Brewery is new and alive and vies with the Blue Ox bar, a roadside tavern with wagon wheels on the walls and a wooden façade emulating old-west saloons. The Brewery is younger, drawing a trendy crowd I want to defend this place from, a crowd older than myself, but one that feels out of place, nonetheless. With its novelty, the Brewery brought a firmness to the soft-edged, tinted impression I had constructed of Baileys Harbor and opened the town to the possibility of change. Now, it seems like each year new businesses replace the old ones. The candy store with the bathtub of taffy became a winery, the coffee shack rebranded and upscaled, and the moccasin shop was demolished. I found myself clinging to my lifelong impressions, stuffing my hands into pockets of remembrances. I liked to believe the kids tossing mudballs on the beach could see, with their inexperienced eyes, the coherence I could no longer find. Or maybe it can only be seen in retrospect, when it starts to fall apart.

When I returned to the condo, I found dusk had entered while I was out. The room appeared as it would in a photograph, as if it were a copy of itself, and I became aware of the loneliness that had been swelling within me through the day. I wanted to cast my growing panic onto something else, attribute it to the changes in town, boredom at the slow-moving book I had been reading, or my reliance on canned soup and frozen pizzas for the next week. But I was simply lonely. Lonely in a place I love. I was reminded of a dream I’d had earlier in the summer, in which I had moved into my first apartment. There was no furniture in the small studio. A box of my belongings sat in a corner. The walls were bare—so much space where I could hang my independence and future. For so long, I had been searching for this place, this blank canvas of a room that the dream offered, where I could obtain the freedom that had seemed incompatible with togetherness. But now that I had shed my reliance on others, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I had carried the weight of dependency for so long, yet I felt its absence not as the lifting of a burden but as the carving of a cavity. That same dreamed feeling, the kind of inexplicable emptiness I thought only existed in nightmares, came to me when I returned to the condo. It was the oppressive kind of loneliness that pushed me deep inside myself, that rushed and crippled without explanation. It was the irrational, embarrassing loneliness I didn’t want to tell anyone about.

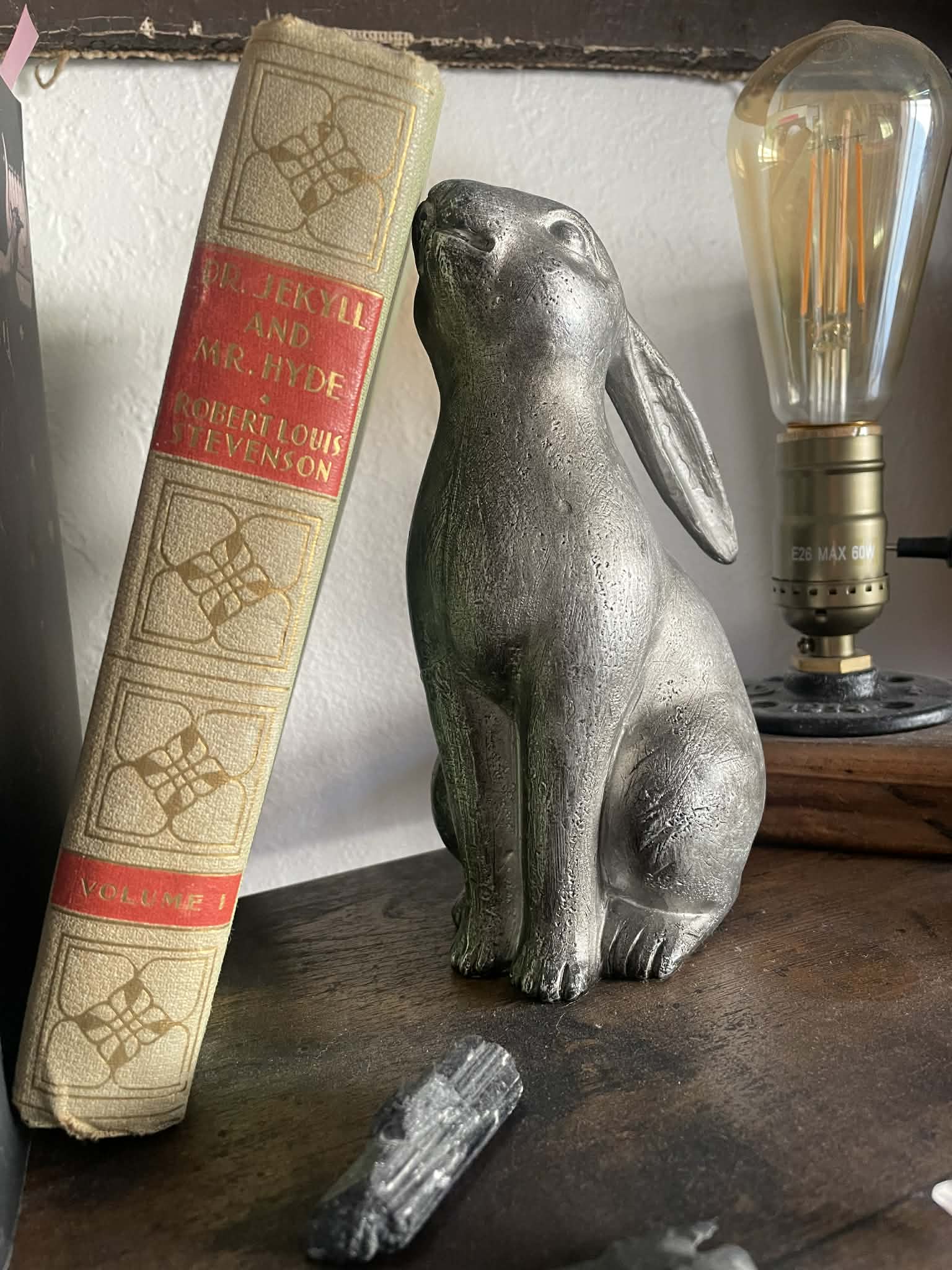

I spent the evening in the warm hold of lamplight, perched over a puzzle, accompanied by the solitude I had thought I desired. Like a buoy at cross-seas, I felt the sinuous lapping of melancholy beating as my pulse. I longed for ghosts. I wanted to see the familiar specters I knew should be in this place. I was haunted by their absence.

The black CD/cassette player on the counter gently crooned the Best of Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. The slow rhythms seemed to understand and synchronize with the bookshelf of potboiled thrillers, the familiar hum of the fridge, the feel of the polyester carpet on my toes. The CD was a relic from my grandparents’ collection, one that I hadn’t heard before. I imagined them listening to this album, here, in this same lamplight. I imagined them sitting in the armchair and couch, unable to see me as I worked steadily on the puzzle. They were comfortable in their privacy, in the tenderness that can only exist between two people. Their lips moved, but I heard no sounds. I focused on the puzzle, while my mind inevitably tangled their love into the playful accentuations of “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off,” of oysters and ersters and saspiralla and saspirella.

The puzzle was a familiar image, a drawn map of the peninsula with cartoon imagery of places I’d visited: the barn where my aunt and uncle were married, Eagle Bluff lighthouse, Wilson’s Ice Cream Parlor, and roadside fruit vendors backdropped by cherry orchards. I restarted the CD once it ran through, poured another cup of coffee because there was more puzzle to do. When I finished, my grandparents were no longer there, but the lake had settled.

Too jittery to sleep, I decided to explore the condo building’s small, shared DVD library. I settled on the green spine of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca, returned to the room, and lay on the couch as Joan Fontaine dreamt of returning to Manderley, dissolving, as if by magic, through the iron gate guarding her past. There was comfort in the whir of the DVD. The darkness outside cocooned and swaddled me as I sank into the film. The suspense softened in the distance between the TV and the couch, and I smiled at Rebecca’s boating accident because it reminded me of the sailboats at the marina. I felt like a child watching the movie, unable to muster the will to keep my eyes open. It seemed juvenile not to be able to fight back tiredness, to resign myself to falling asleep on the couch. In that weakness, I felt both infantile and adult. I felt calm at last. My loneliness was an aching muscle, one that was exerted but resting, now only a faint memory of pain rather than pain itself. I couldn’t understand how it ever hurt so much. I bundled myself in this moment, in this warm childish feeling, where the demands for independence and constancy were insignificant compared to the weight of my eyelids. All was quiet but the buzzing dialogue of the movie and the rush of waves lapping onto the shore, through the open window, lulling me to sleep before the movie ended.

Ben Tamburri is a junior at Amherst College and an editorial assistant at The Common.