MARNI BERGER interviews ROWAN RICARDO PHILLIPS

Rowan Ricardo Phillips was born and raised in New York City and is a graduate of Swarthmore College and Brown University, where he earned his doctorate in English Literature. He is the author of two books of poems, Heaven and The Ground: Poems, as well as a book of essays, When Blackness Rhymes with Blackness, and a book of translations of Salvador Espriu’s Catalan collection of short stories, Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth. Rowan is the winner of a 2015 Guggenheim Fellowship, the 2013 PEN/Osterweil Prize for Poetry, a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award, and the 2013 GLCA New Writers Award for Poetry. In 2015 he made the National Book Awards Longlist for Poetry. He has taught at Harvard, Columbia, Princeton, and Stony Brook, and he is a fellow of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. He lives in both Barcelona and New York City.

Phillips and Berger discussed the stenography of poetry and the “beautiful challenge” of geography as “fate.”

Marni Berger (MB): Your poem “The First Last Light in the Sky” appears in Issue 09of The Common. In it, I see the sun setting over the sea, and the night rising up. But even the image of a sunset could be open to interpretation; the poem has a misty, dreamy quality. Do dreams play a role in your writing process?

Rowan Ricardo Phillips (RRP): Dreams, no—not really. But the idea that the mind on its own creates a reality out of unreality, yes—and that this takes place at hours when a place seems more unusual to us, yes.

I’m not quite all in on dreams in regards to the imagination. That relationship feels too on the nose––too explanatory, too possible. A dream is already a real thing before the poem happens. And if there’s one thing poetry is it’s stenography––even of dreams. But we’re back to Aristotle with this: “the poet should prefer probable impossibilities to improbable possibilities.”

MB: Carl Jung famously spoke of the sea as the symbol of the collective unconscious, the shared unconscious minds of humans. Would it be an over-analysis to suggest that in “The First Last Light in the Sky” the collective unconscious is as much of a “place,” if not more so, than any “real” place?

RRP: To an extent, yes. Psychoanalysis does such a convincing job of sounding as though it has the answers to the creative process. But poetry is so much older—and usefully archaic—than psychoanalysis. The goal of any poem is likely to present to the reader a shared unconscious mind. At the same time, those are very loaded terms.

MB: Could you elaborate?

RRP: By this I mean that the idea behind a lyric poem is that there is a reader and an “other,” the “other” being the poem before the reader, which—if the poem works—the reader accepts [and hears] in his or her own voice, if only for that moment and hopefully longer than that. At its core, a lyric experience is an experience of possession. The idea that we are inhabited by a force with its own mind and movements is more arcane, messy and, to me, far more reliable than psychoanalysis. What “The First Last Light in the Sky” seeks to do is to make the place as much about the sounds and phosphorescent sense of things that the mind makes. It becomes a collective thing, hopefully, in being read. This is how the poet, as an individual, enters into a collective understanding of a world, of right and wrong, of what art is and how and why.

MB: Line 12 of the 24-line poem splits “The First Last Light in the Sky” in half with the word “mirror,” turning the actual poem into a kind of mirror: “As its other, as though to mirror la.” Would you say the poem itself is reflective, structurally, but also in subject matter?

RRP: Something similar happens in a poem in The Ground, “Embrace the Night and Get Thee Gone”—although in that case there’s a stanza break and the poem starts to retreat on itself, making variations from the repetitions and forming a sort of image: a structure and its reflection in the water.

Poems have their own inner-logic and one of the tasks of the poet is to know how to listen for it. It’s a rare skill. I like to think that poems, being aware that they are poems, look at themselves and start to arrange, deepen, and intensify their own experience of being made.

MB: This poem turns musical—“la” appears throughout its second half. How closely linked do you see songwriting and poetry?

RRP: That’s a tricky question. Poetry is innately musical. And songwriting, at its best, is an art that can reach countless people, moving them in ways that enhance our experience of being human. That said, songwriting can get away with a whole host of things that poems simply cannot. Songwriting can embrace the flabby, wobbling nature of making songs because a song can still give sustained pleasure from other aspects, be it melody, rhythm [or] the “catchiness” of the whole thing. But when you lay out just the lyrics of a song you love, more often than not something feels like it’s missing, don’t you think? (Glyn Maxwell wrote beautifully on this in his book On Poetry.)

I love “la” in that moment as well as those that follow. It was the right word there: “la”… but that’s not songwriting. It’s song––there’s a vital difference. It’s like the organization versus the organ.

MB: Let’s discuss place. I’ve read that you live in New York and Barcelona. Can you talk about your experiences living in both cities? They are two very different cities, and yet, in my experience, they are alike in how they collect those who don’t “fit in” “elsewhere.” I wonder if you share that observation?

RRP: Well, both New York and Barcelona are major port cities and as such they have at various points harbored some of the great traffic of the world. And they’re both cities that bit-by-bit incorporated the adjacent areas around them. And both are highly receptive to people seeking a narrative-altering experience. What happens when people find a narrative-altering experience is that they tend to think that they then know the narrative. So they’ll tell you all about New York or Barcelona not because they now “fit in,” but because they’ve taken some small part of it over. People don’t “fit in” in Williamsburg or Las Ramblas––those neighborhoods would feel very different if they did.

MB: To switch gears: Your poems “engage the acts of post-9/11 memory and ruin, lingering in interrupted or merged landscapes of art, rhetoric, and marginalia.” How does this description of your work (from The Poetry Foundation) jive with your mission for it?

RRP: My mission is always to write a good poem, one syllable at a time. I’ve never thought about writing poetry in any other way aside from that.

MB: What does marginalia mean to you, and how does that definition direct your writing?

RRP: You’re timing with this question is eerie. I was just today talking about marginalia with a good friend––in fact, the Benedict Robinson from [my poem] “The Mind After Everything Has Happened.”

My answer is marginalia. And I stand by that: there is nothing marginal in writing poetry. Everything is marginalia and nothing is. It’s just a question of your angle of approach, how you hold the gem to the light. The best poem you ever write must become marginalia for what comes after or you’ll be jumping up and down in the same spot all of your life. Milton is filled with marginalia. That marginalia is also known as the works of Virgil. What a poet learns is when to bring things in from the margins and when to nudge things closer to the margins. But in general, there’s a sense of hierarchy to thinking in terms of margin and center that I don’t subscribe to. Neither as a writer nor as a citizen.

MB: Professionally, you are not only a poet of course—you are a critic, a teacher, a translator. How do you switch hats? For instance, can you write poetry and teach on the same day?

RRP: Definitely. I wrote “The First Last Light in the Sky” on my way to Princeton to teach.

MB: In your interview with The Rumpus, you paraphrased Heraclitus. You said, “Heraclitus, I believe, said that geography is fate. That, then, is what tethers us to the world. The rest is pulling on that tether.” Looking back on your own quote, do you still adhere to the notion that geography is fate? Some could see that as suffocating, a trap—but how do you see it?

RRP: The way in which you described Barcelona and New York you seemed to agree. You are where you are, for one reason or another. This can only be suffocating or a trap if it prevents you from living like a fully realized human being. I’m not scared of being fated to a place in part because fate doesn’t scare me. Instead, I accept it as a beautiful challenge. I was born and raised in New York. I am Antiguan by descent. The odds are stacked against my being the best writer from either of those two places. But these are the places I’m from. A poem starts in a place. I love the pressure of that. Pressure, as the saying goes, makes diamonds. Any poem I wrote of a place is my way of writing “Rowan was here.” Because I was. And the poem still is.

MB: In Bryant Park on July 7th this year Tony Hoagland said (in a quote recorded by “Last’s Nights Reading”): “It’s a poet’s job to locate particular moments we are familiar with but have never formally catalogued.” Do you agree?

RRP: I don’t think of poetry as a job, I think of it as a vocation. I find myself grateful for any good poem that gets written. A good poem is its own aphorism. So I tend to skip the aphorism and go straight to the poem.

*

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s poem ’The First Last Light in the Sky” appears in Issue 09 of The Common.

Marni Berger is a writer and teacher living in Portland, Maine.

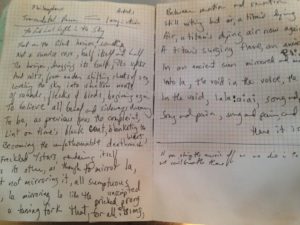

Photo Credits: Headshot by Sue Kwon. ‘La Delta de l’Ebre’ by Núria Royo Planas.‘El far de Sant Sebastià,’ ‘Cityscape, Manhattan’ and photo of poem draft by Rowan Ricardo Phillips.