By MEGAN KAMALEI KAKIMOTO

Reviewed by MARIAH RIGG

A mentor once told me, “you write to the places you are not,” and I think that is true for not only what I write, but also what I read. Since moving to the Southeast U.S., with its millennia-old forests and rolling thunderstorms, I’ve taken to reading about the places I’ve come from: Oregon, Southern California, and the islands upon which I was born and raised, the place where my family has lived as settlers for over three generations—Hawaiʻi.

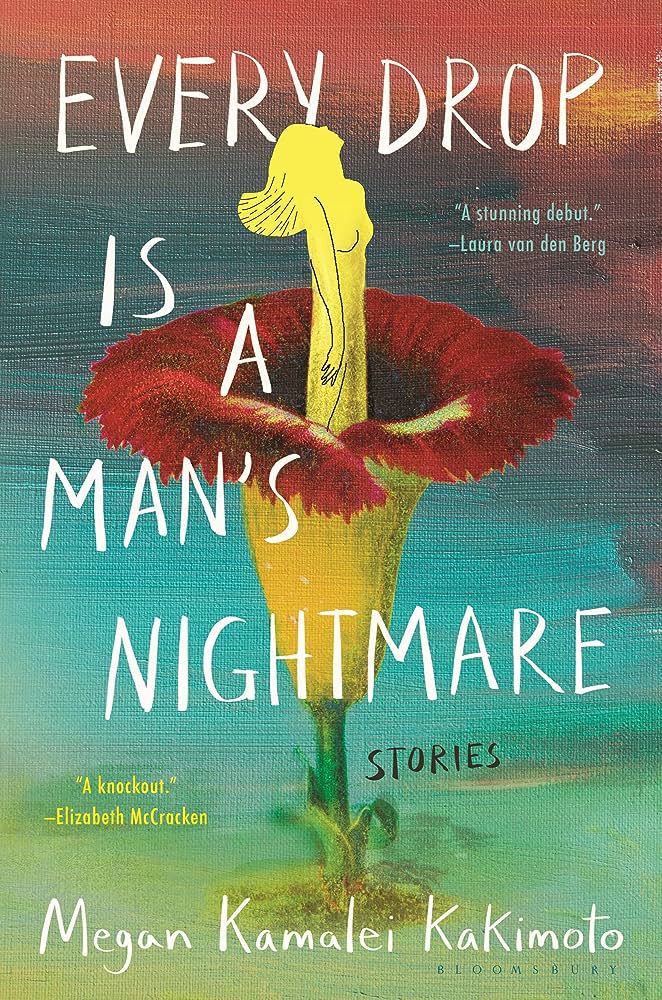

I first learned of Megan Kamalei Kakimoto from her agent, Iwalani Kim, at a spring launch reading for Puerto del Sol and Black Warrior Review in 2022. Like Kakimoto and I, Kim grew up on the island of Oʻahu, and went to high school, coincidentally, down the street from the house I grew up in. She didn’t tell me I had to read Kakimoto’s work, but she did mention how rare it was to meet someone from Hawaiʻi in the literary world, let alone someone from the same island and neighborhood. She’s right: there is not enough attention paid to writers from Hawaiʻi, particularly when it comes to Hawaiian and Pacific Islander writers, and far too many people write about Hawaiʻi without knowing anything about its people, its land and culture. While I did not read Kakimoto’s work that night or the nights after, stuck in the swirl of AWP, I did read it once I’d gotten back to my studio apartment in Knoxville. Once I started, I could not stop, ordering back issues of Conjunctions and Boulevard to read “Leaving Cynthia” and “Baby’s First Lūʻau,” reading and rereading my favorite story of Kakimoto’s in Joyland, the story that is now the titular one of her debut collection: Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare.

Comfort is not the right word to describe Megan Kamalei Kakimoto’s work, though it is true of how I felt spending time with the characters and settings of her debut collection, so many of which resembled the people and places that populated my own childhood. A better word, perhaps, would be unease, as Kakimoto’s collection reads like a glass of water filled to the brim. Kakimoto is an obvious master of the sentence, the surface of her language clear and clean, each phrase whittled to its most essential parts, each image painted in brushstrokes of the utmost confidence. Her lines cross time and space, building an entire world in just a few moments, as she does at the beginning of “Story of Men,” when the Menehune whom Leimomi finds in the discarded dryer left out on the curb by her husband cries out at Leimomi’s pain: “It was a cry that tore caws from the feral roosters’ jowls, a cry that reached even Boy Two, the troubled child, below the Nimitz bridge, where he smoked pakololo and set several strange fires with his buddies,” and at the end of “Temporary Dwellers,” when the narrator, anticipating the loss of her lover, recalls hiking the Nāpali coast with her mom: “I consider my mother’s bony hands on my shoulders, holding me in place as I stood perilously close to the Nāpali cliff. I marvel over how I am always finding a precipice, always looking for the nearest ledge to try my luck. I think about the girl’s hands inside me, and the soft sounds she made in this bedroom next to mine.”

Beneath the surface of Kakimoto’s lines, there is always the feeling that something remains hidden, that the hydrogen bonds between molecules will break and the water will spill. In many of Kakimoto’s stories, told by and about women, this proves to be less a feeling and more a prediction, as the water does not just spill, but the glass itself breaks. The water proves to be not just water, but blood. It clots in Sadie’s “wet lip of underwear” in “Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare,” as she and her parents cross the Pali with a container of pork, and later, in her twenties, soaks the pull-ups Sadie wears through her pregnancy, finally giving birth to a mini puaʻa, a fulfillment of Pele’s vengeance for the kālua Sadie transported across the Pali all those years ago. It runs like the stories of The Madwoman the narrator tells her hapa son, Toby, in “Madwomen,” explodes like the violence of the narrator’s Aunt Judy as her fists pummel the narrator’s cousin Kalahiki in “Hotel Molokai,” and blooms like the form of the narrator’s deceased wife, Haunani, does in “The Love and Decline of the Corpse Flower,” from a blossom that smells “like the curdled remains of a backed-up disposal, like a cat’s corpse bleeding into the carpet.”

For every story where the glass breaks, there are stories that end with the threat of shattered glass and others that begin with the glass already in pieces. In “Temporary Dwellers”, one of many queer love stories, and the first story that Kakimoto ever published, the narrator falls for a refugee from Kauaʻi, a girl who lives in her home and whom she knows, by the end of the story, will leave her, returning to join the protests on “what remains of Kauaʻi…scattered debris, swollen carcasses, a smoky residue settled over what had once been the fiercest of the islands, the landmass with resistance settled into its soil.” In “Some Things I Know About Elvis,” a woman drinks at a Mōʻiliʻili bar with her friend, Sara, who visits every summer, talking about Elvis impersonators and only revealing to the reader, in the story’s final pages, that Sara is in fact her sister, born to the family her father had after he “left the house one morning for a shift with his construction crew and never came back.”

Always, the question of what it means to live as a Native Hawaiian woman in an illegally occupied territory roils beneath the surface of Kakimoto’s stories. The cast of Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare struggles with the ghosts of colonization and the impossible ideals that are set for their lives, their work, and their bodies by the cis hetero colonial patriarchy. Much like Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl,” the opening story of Kakimoto’s collection, “A Catalogue of Kānaka Superstitions, as Told by Your Mother,” lays out expectations that the women of Kakimoto’s collection will subvert and, at defining moments, explicitly break. Settler colonial standards are directly opposed by ancestral wisdom and superstition here and in other stories like “Aiko, the Writer,” where the grandmother of the main character, Aiko, sets rules for Aiko to write and live by:

“Don’t bother with accessibility. Even when you write white, the white readers won’t make sense of it. Bother with specificity. Be exacting and specific. Write in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi when you can. Write dialogue in pidgin, because dialect is important. Most importantly, honor the kapu. Do not write about what you cannot write about…You cannot write about the Night Marchers.”

And yet Aiko, after failing to sell her first collection, explicitly breaks these rules. She follows her agent’s advice: “Give the readers what they want!”, leaning into her Indigenous heritage and writing a collection that is linked through the Night Marchers. But when the first draft of the manuscript is finished, the pages begin to vibrate. When Aiko goes to Austin, Texas for a writers’ conference, the Night Marchers come for her, along with her grandmother, who appears in the shape of a moʻo, and though Aiko’s agent is excited to sell her Night Marchers’ collection, the manuscript disappears from Aiko’s backpack on her return flight to Oʻahu.

In an interview with Honolulu Magazine, Kakimoto talks about how she’s worked through writing about her own Native Hawaiian ancestry: “the pressure to write it right, to do justice to it, completely silenced all my interest in writing about Hawai‘i…I was really scared about getting it wrong. But I had a slow realization and began to challenge all these ideas of a monolithic Hawaiian cultural experience. They’re just not true.” Reading Kakimoto’s stories through this lens, through a multi-faceted, complex view of Native Hawaiian and local culture, reveals Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare to be a subversion of preconceived, colonial notions of what Hawaiʻi and its people are and should be.

The women of Kakimoto’s debut collection are fully realized and embodied, with recognizable needs and complex desires that drive conflict both on and off the page. “Ms. Amelia’s Salon for Women in Charge” follows Kehaulani as she debates how she will pay for the full Brazilian she gets to please her haole boyfriend at a salon that only accepts personal traits as currency. “Touch Me Like One of Your Island Girls: A Love Story,” tells the story of office manager Mehana who, desperate for a raise and to regain her ability to orgasm, interviews at a haole-owned company built around mainland demand for Hawaiian “Island Girl” sex workers. In the words of Elizabeth McCracken, the eleven stories of Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare not only refuse “to pull [their] punches,” they also provide space for nuanced depictions of Native Hawaiian and local women, a place on the page to let it all hang out.

Kakimoto’s stories do not operate on the one-dimensional plane of settler colonial experience. Instead, many of the stories in Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare toe the line of the speculative to upend packaged, paradisiacal images of amusement park Hawaiʻi, revealing the uncanny reality of the islands: a place of resistance where every day people are expected to work and live. With this debut collection, Kakimoto makes herself a household name not just when it comes to the literature of Hawaiʻi, but proves herself to be one of the best short story writers writing right now.

Mariah Rigg is a third-generation Samoan-Haole settler who grew up on the illegally-occupied island of Oʻahu. Her work has been published in Oxford American, The Cincinnati Review, Joyland, etc., and has been supported by organizations such as VCCA, the Carolyn Moore Writers’ House, and Oregon Literary Arts. In 2023, Mariah’s chapbook, All Hat, No Cattle, was published as part of the Inch series at Bull City Press. She holds an MFA from the University of Oregon and is a PhD candidate at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where she edits fiction for TriQuarterly and creative nonfiction for Grist, A Journal of the Literary Arts.