Photo courtesy of author

Ithaca, NY

I want to start by saying that this is not about when I was in a New York city cab and the cabbie and I struck up a concrete jungle duet about where we were from—Gaza, Sudan, Rwanda, Nigeria, Dominican Republic, Pakistan, Ukraine, India…—and what winds, fair or foul, had blown us to the country that’s being made great again by a certain real estate developer. I want to start by saying that in what I have to say there is no New York City or cabbie. That’s not the kind of story this is. Rather, in this story there is a sister—or sisters—and a land—or lands.

I want to start by saying that I propose, simply, a new topos for going “back home,” for the return to Ithaca. I call this topos Sisterland.

And I want it to be “re-cognized” that this Sisterland is not a Motherland. Rather, Sisterland is what you go “back home” to after losing your mother.

My mother died twelve years ago. Six months after that my lover fled what he called the propellers of my traumatic motherlessness, or the traumatic propellers of my motherlesness. I want it to be clearly understood that this story is not about any fugitive lovers.

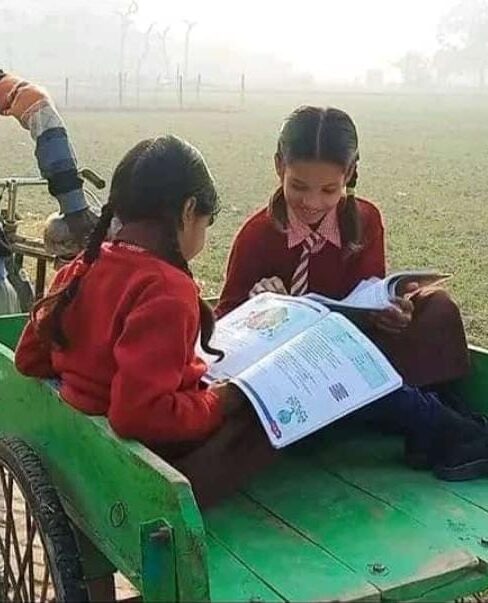

What I want to say, instead, is that since my mother died, I’ve returned—first wide-eyed and then eyes narrowed, no longer every year but every other year or every third year—to my Sisterland. Because my sister, my genetic duplicate, is all that now remains of my birth family unit in what used to be my Motherland.

And I want to say that we sisters have fought and made up, and we are close, but a Sisterland is not a Motherland.

You get that. And so you will let me go on to say that a Sisterland can be loved too, loved complicatedly and stormily, but it’s a different storm. A storm of more conditional love. Less of a free gift.

And I’m desolate and mortified that I find I can only half love this place called Sisterland, this place where I was born to a mother now dead. And that the other half of my feelings for what is now the land where only my sister now lives doesn’t fit right onto this half love. An aperture unto what it means to lose your mother is stuck in between the two halves.

The descending Boeing 707’s engine can pretend to be the lullaby once in my mother’s veins singing my unborn heart to life if I close my eyes and pretend, but it misses. Instead, the stewardess’ practiced saga of arrival sings the dogged return of a stranger to a strange Ithaca—to Sisterland.

In Sisterland, beneath the skin and membranes of my sister’s face sleeps my mother. But though my sister also has a heart made by my mother, it isn’t the heart that made mine. I return to my sister who is a doppelgänger just unheimlich enough to show the crack in the ground through which my mother vanished.

I want to say that I don’t know if I want to say that when your mother dies you recognize that the only Motherland you ever had, especially if you left it behind, was your mother. Because who am I to insist on it? Because if you were unloved, neglected, abused, or abandoned by your mother, this means jack all, doesn’t it?

So what do I want to say?

I want to say that if I was in that New York cab with that driver after all, we’d be saying that we’d left Motherland behind. We’d be saying that we’d gone to look for, O, or America, our new-found-land, and thinking our new-found-land—“a far fairer world encompassing”—was waiting for us, radiant, just around an endless corner, just behind a rusty corrugated warehouse door, to say, “Hello, Hi, How d’you do, So pleased to meet you, Howdy Dammit,” we stayed, and our mothers grew old. And we’d both know that our flights back to the old country will now drop us in Ithaca, where our siblings meet us and even rejoice at our return. And that when we get “back home” we’ll glance at the cracks in the floors of the rooms of our mothers’ lives. But we won’t dip our toes into the cracks because we can’t bear, don’t dare, to vanish down the rabbit holes of our past lives. And we won’t dare to close up the cracks because we can’t bear to lose our mothers all over again.

And so, in this way, I want to say, my Sisterland will be there, when I go “back home” now, to remind me that I once had a mother.

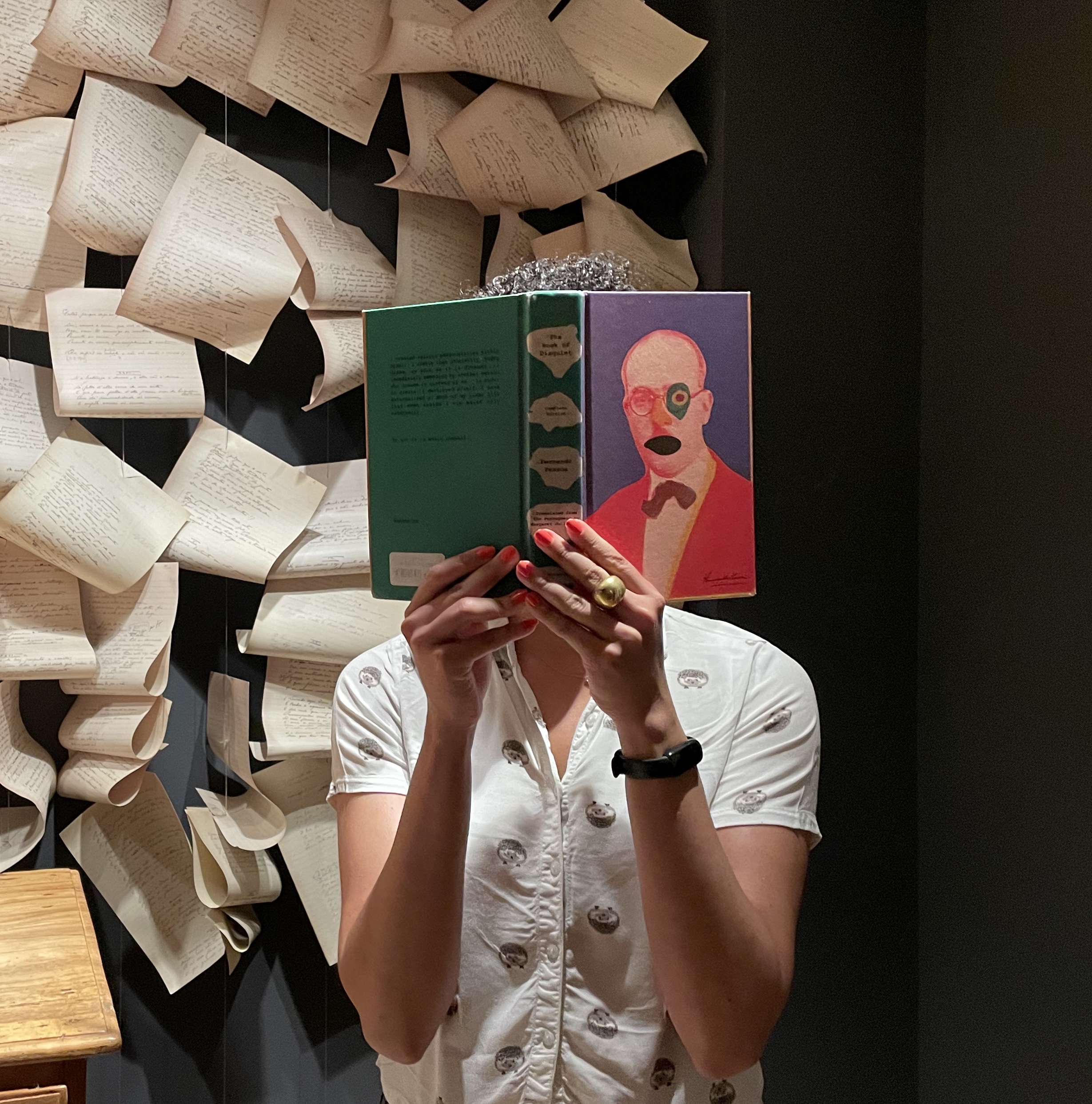

Nandini was born and raised in India, has called the United States her second continent for the last thirty years, and is wondering where to land next. Wherever she’s lived, she’s generally turned to books for the answers to life’s questions (that includes philosophy and recipes). Her first novel Love’s Garden appeared in October 2020 and has garnered praise as a fascinating and well-crafted journey into India’s complex past” (Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni). Shorter work has appeared or will in Cincinnati Review, Bellevue Literary Review, Chicago Quarterly, RUMPUS, Oyster River Pages, Saturday Evening Post Best Short Stories 2021, Bombay Review, PANK and more. Workshops and residencies include the Kenyon Writers Workshop, Bread Loaf Writers’ Workshop, Vermont Studio Center, VONA, and Ragdale Writers Residency. Awards and honors include a Pushcart prize nomination (2021) and first runner-up for the Los Angeles Review’s flash fiction contest (2017).

She lives outside Houston and teaches English literature at Texas A&M University. She can be found at Amazon, Author’s Guild, X, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, Goodreads, Substack, Medium, Bluesky, YouTube, Tumblr, and her Blog.