SASHA BURSHTEYN interviews KYLE CARRERO LOPEZ

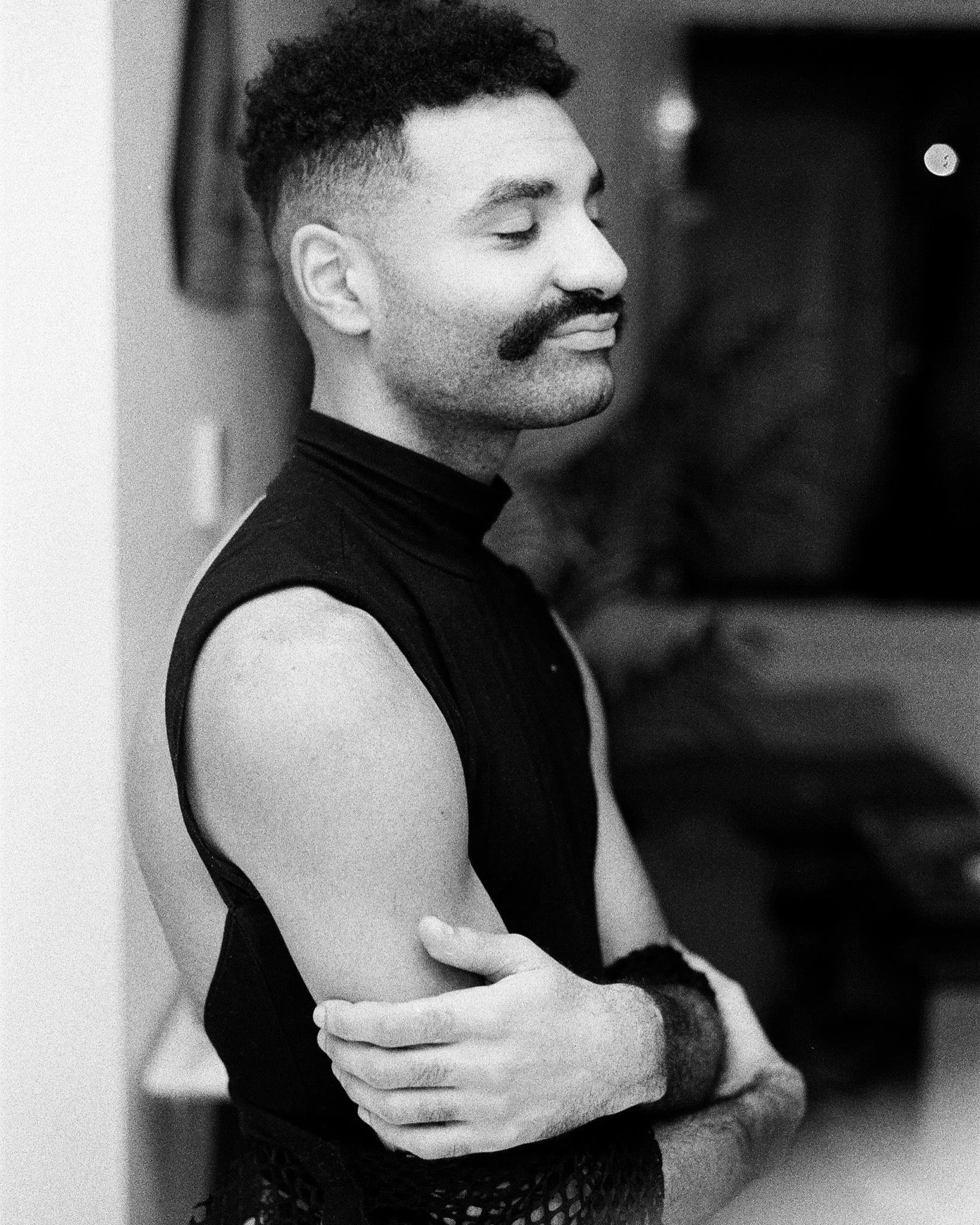

Recently published in The BreakBeat Poets Volume IV: LatiNEXT, Cuban-American writer Kyle Carrero Lopez holds an MFA in Poetry from NYU and is the co-founder of LEGACY, a production collective by and for Black queer artists.

Carrero Lopez is unapologetic about his poetic concerns. In this powerful interview, he explains how sonnets give him the ultimate space to practice his multitudes in a pressurized space, and the way anti-Blackness is provoked by capitalism, dangerous clothing, and cultural brutalization.

Sasha Burshteyn (SB): You have such a feeling for form in your collection MUSCLE MEMORY— “After Abolition” and “Inheritance” are both sonnets, and “(SLANG)UAGE” is in the Oulipian beautiful outlaw form. What draws you to these forms? What do you feel they offer your work?

Kyle Carrero Lopez (KCL): In the case of the sonnets, something about the compression really works for me. I appreciate that a sonnet demands a turn via the volta. It’s a pressurized space for those two poems. They’re intense poems as far as the subject matter, but I wanted to work with brevity in both, and so the sonnet felt like the right pot to put the poem in. Terrance Hayes has said that a sonnet is a room that you can scream into.

With the beautiful outlaw, I was introduced to that form by a Marwa Helal poem—she’s actually worked in that form a couple of times. It felt like the right way to get into all the different sorts of lexicons and forms of slang and ways of thinking about language that are specifically informed by the different cultures that I’ve been born into and come into; whether it’s academic jargon or Black American vernacular or Spanglish. It moves through a lot of different places. The constraint of the form also attracted me because I feel like I’m working and speaking in all of these different ways at different times, and I often feel that the fullness of how I view the English language and how I use language is never captured, really. Which is okay! I think there’s something very human about the need to be different people at different times depending on the context. But I was really interested in trying to hold a multiplicity of selves in one place, because they are just me all the time, upstairs.

SB: Clothing appears frequently in your poems. “Ode to the Crop Top” celebrates the crop top and what it connotes. “Charge it to The Game” is about the cruelty endemic to manifestations of glamor in our society. So clothing is a material good, an extension of the speaker’s body in society, and a symbol.

KCL: I have so many poems about clothing. I’ve always had an interest in fashion and in clothing, period. I worked in fashion for a while when I first moved to the city. Then over time I became increasingly disillusioned with it because the closer you get to fashion, the more you learn about everything about it that’s horrible. But I always maintained an interest in the way things were made and where things come from. And I like clothing as a frame that allows us to speak about ethics. Because it’s something that we all need, but we don’t all think excessively about the clothes we wear, or where it comes from, or who made it. I’m really interested in the tension between what goes into manufacturing and also the manufacturing of the self that goes into fashioning one’s personal style. It’s something that is really sacred to me and to so many queer people. But the cost of that is often danger. So in “Ode to the Crop Top,” I wanted to amplify the strangeness of a piece of clothing being so consequential.

SB: A lot of your poems circle around the commodification of Blackness and Black culture, the extractive nature of culture at large, and the way that this circulates on a global scale. This comes up especially in “Black capitalist wet dream” and “Beauty Examined.”

KCL: Organically, I write a lot about anti-Blackness and the different ways that it manifests. I find that it’s difficult to explain to someone who thinks the race issue is overblown. Or that it’s easy to understand that police brutality is an issue, but it’s not always easy to understand the connection between the physical brutalization of Black people and then our cultural brutalization. It’s almost like we really can’t have anything for ourselves; when we do have something for ourselves, it’s so quickly taken and churned into capital. In writing “Black capitalist wet dream,” I was getting at how even pro-Black spaces, without continued diligence and critical thought, can very quickly become anti-Black. Or if not explicitly anti-Black, they can play into capitalism, which many would argue is inherently anti-Black. So within that poem, there’s tension between a space that’s meant to celebrate Black culture and Black music and a crowd that is ultimately ignoring an issue like rent control. Or the tendency of spaces that are meant for fun, and how those spaces can allow for disengagement from what’s going on on the ground. “Beauty Examined” is a lot about the commodification of Black pain in art. There’s meta commentary that happens, like the line “this is an ugly thing to do and here / I am doing it”. One of the underlying goals of the book, or at least, an underlying theme, is challenging beauty. Beauty can be very distracting, and beauty can be insidious, an agent of hegemony. We can overlook a lot by focusing too much on beauty. That’s something that frustrates me about art in general; it can frustrate me about poetry, sometimes. Sitting with ugliness is just a much greater concern in the writing that I want to do. From there, maybe more complicated beauties can be excavated.

Kyle Carrero Lopez is a Cuban-American writer. He co-founded LEGACY, a production collective by and for Black queer artists. His work is published in numerous publications as well as anthologized in The BreakBeat Poets Volume IV: LatiNEXT (Haymarket Books, 2020) and Best of the Net. He holds an MFA in Poetry from NYU.

Sasha Burshteyn is a poet, born in Russia and raised between Brooklyn and Eastern Ukraine. Her work has appeared in Copper Nickel and Pigeon Pages, among others; been nominated for a Pushcart Prize; and been supported by National Geographic and the Watson Foundation. She is a Goldwater Fellow at NYU, where she’s currently pursuing her MFA. Find her on Twitter: @sashabursh.