My mother has found the book in her files, among the stacks of papers and paid bills rescued from the cabin. Though it doesn’t look like much now, in its drab brown cover with faded red lettering, it was the most treasured volume of my childhood. My grandmother, who loved a good fairytale, whose favorite book was Alice in Wonderland, read Prince Uno to me, and then I read it myself, entranced, curled uncomfortably in one of the green wicker chairs with the scratchy orange cushions—only a slight improvement over the impossibly hard couch. The only two comfortable seats were my grandparents’ recliners, in which they sat to read, watch the Patriots, drink five o’clock cocktails, and order people around. While my cousins and half siblings were age-mates and bunked together at the lake for a week or two, I was ten years younger, without workmates or companions. This afforded me little leniency—I was still tasked with pulling onion grass from the swimming area and sent down to fetch laundry from the moldy basement—but because I was often the only child here, my desires were more often indulged: I could eat as large a slice of pie as I wanted, and often the flavor of pie was decided by me. And so, when I wasn’t doing “jobs” for my grandfather, or cooking with my grandmother, or picking raspberries from the neighbor’s vines, or helping G&G measure the depth of the lake, I was reading. Prince Uno: Uncle Frank’s Visit to Fairyland occupied me for many summers.

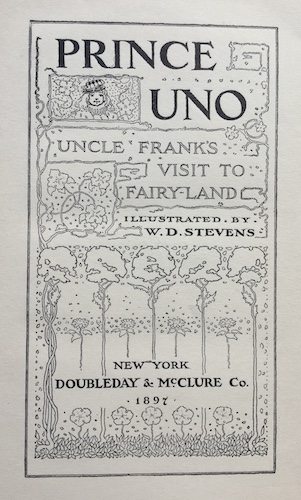

Published in 1897, Prince Uno is not a classic. Or, if it was once well known, it’s now obscure. No one I know has even heard of it, and the Internet turns up barely more than an image of the frontispiece from the Library of Congress. (If any readers know this book, let’s hear from you!) So, when my mother shows me what she has found, I instantly tug it out of her hands.

This volume is the replacement version, the one my grandmother found, after many dead-end inquiries, from a used bookseller. The original first edition, which my grandmother read from, is now beyond use, spine cracked and pages crumbling. It’s inscribed with the names of successive owners: my great-great-aunt Stell, whom I did not know; Sylvia Weingart Schwarz, my great-grandmother who died when I was five, whom I do not remember; and Sylvia’s only daughter, my grandmother, Eleanor. I’m told my literary interests come from Sylvia, who wrote a book of light verse for children, published in women’s magazines, and held exquisite, themed dinner parties with literary menus (she had a cook).

My grandmother was a woman of science, a chemist, but she was also a facile writer herself and a lover of stories. I hear clearly her alto voice describing Uncle Frank’s incredible discovery of the fairies as they cavort one fine day in the surf. He follows their prince down a steep flight of underground steps, where he encounters Fairyland and, oddly, an adjacent town of humans who are fairy-sized. While the fairies need for nothing—all their raw materials are supplied by desire, rather than by nature—the humans must toil to farm and harvest and extract from the land the resources they need to survive. Not even in our wildest dreams can humans detach from the physical, the tactile.

I settle in, arranging myself in a plastic Adirondack chair with a red chenille pillow on the sun-full dock, partially in the shade of an umbrella jerry-rigged not to blow away. (In my childhood, we had no use for shade.) I am immediately confronted with two intriguing disclosures, one of which I remember, and one I do not. I recall that Uncle Frank was not a renowned author; this was his only book, and the title page lists simply “Uncle Frank.” What I did not remember was what occasioned these tales: Frank’s young nephew was dangerously ill. The author writes in the introduction, “In order that he might endure the extreme suffering caused by the medical treatment, it was necessary that his mind should be diverted from his sufferings on that day. Before the sun should set he would be either convalescent or past help.”

The timing is fitting; I, too, am ill. Not dangerously so, but down with a fever, severely achy and uncomfortable. But I am not too feverish to read, to sit outside with the waves lapping, the warm lake wind bathing me in what I feel to be a nourishing broth. The whimsy and nineteenth-century geniality seduce me, and I smile at the exchange in which Uncle Frank says to the fairy prince, “Well, most mighty potentate, I have taken dinner with you and have enjoyed it very much…. May I ask your name?” To which the prince replies, “Uno.” “Why, no; I don’t know,” Uncle Frank says. “I am sure I never heard your name in my life!”

Uncle Frank then requests the name of the princess and receives the reply “Ino,” which further befuddles him, and he answers, “Of course you do, but have you any objection to telling me?” At that point, my grandmother always laughed and looked at me to make sure I was as amused as she. On the dock I am struck by a different clever moment, in which Frank complains that the delectable dinner the prince has served him has not even begun to sate his appetite. Prince Uno erupts into gales of laughter, to his guest’s great offense, realizing that while he has shrunk Uncle Frank to three inches to fit inside Fairyland, he has neglected to downsize the large man’s appetite.

Toward the end of the book, Uncle Frank and Prince Uno visit a poor boy confined to a chair. Despite his condition and the necessity that he be left alone in the woods all day while his family is off earning a living, the boy never complains and always thinks of others first. To ease his suffering, and as a reward for his selflessness, the prince gifts the boy the most marvelous wheelchair, complete with roll-up curtains and roof to protect from weather. Most spectacular of all, the chair comes with meals on demand made by a tiny fleet of fairies who appear instantaneously in the kitchen stored in one of the wheelchair’s arms. While Prince Uno and Uncle Frank derive great satisfaction from making the boy deliriously grateful and happy, I find I am absurdly envious. How unfair that in my hour of need I don’t have a fairy prince at my beck and call!

Toward the end of the book, Uncle Frank and Prince Uno visit a poor boy confined to a chair. Despite his condition and the necessity that he be left alone in the woods all day while his family is off earning a living, the boy never complains and always thinks of others first. To ease his suffering, and as a reward for his selflessness, the prince gifts the boy the most marvelous wheelchair, complete with roll-up curtains and roof to protect from weather. Most spectacular of all, the chair comes with meals on demand made by a tiny fleet of fairies who appear instantaneously in the kitchen stored in one of the wheelchair’s arms. While Prince Uno and Uncle Frank derive great satisfaction from making the boy deliriously grateful and happy, I find I am absurdly envious. How unfair that in my hour of need I don’t have a fairy prince at my beck and call!

But my attention is quickly distracted by a third aspect of the book I didn’t remember—the illustrations. Though they appear on nearly every page, they look new to my older eyes, and I wonder if this is because my first encounter with the story was aural: I developed my own mental pictures and nothing ever superseded them. But today I am spellbound. The drawings are delicate and intricate and joyous and lift my spirits, successfully diverting my grumpy mind from being jealous of a fictional boy.

I was, in fact, extraordinarily well-cared-for here at the lake, by my opinionated, doting grandparents. I was taken out in the sailboat, fed home-canned peaches, and given another remarkable gift that went unrecognized at the time: boredom. I was often bored of catching frogs on my own, of mastering the dead man’s float to no one’s astonishment, of doing the silly chores. I wanted an opponent for the oversized checker game played on a rug the size of a coffee table. I wanted to be surprised by the contents of the candy jar, which disappointingly held only sugar-free  candies after the onset of my grandmother’s diabetes. (Though there were always cookies or fudge or ice cream for my grandfather, who would rather have died than forgone sweets after every meal.) And rereading Prince Uno, I am bored again. Only the superficial enchants me—the pictures and Victorian mannerisms—not the plotting of the rescue of Prince Uno’s son, kidnapped by malicious wood sprites. I realize I am speeding through. The book has ceased to be a captivating stand-alone narrative. Instead it has morphed into something deeper and more integral, both more and less remarkable. I have absorbed the Fairyland adventures so thoroughly that they have become a burbling, familiar background against which select incidents rise up and stand out for the commotion they create in my memory. For the moments in my own life they snap into being. Frank’s outsized appetite is now a tall tale like so many others told and retold at the cabin: Remember the time Chris and Sean caught two trout by bashing them over the head with a paddle?

candies after the onset of my grandmother’s diabetes. (Though there were always cookies or fudge or ice cream for my grandfather, who would rather have died than forgone sweets after every meal.) And rereading Prince Uno, I am bored again. Only the superficial enchants me—the pictures and Victorian mannerisms—not the plotting of the rescue of Prince Uno’s son, kidnapped by malicious wood sprites. I realize I am speeding through. The book has ceased to be a captivating stand-alone narrative. Instead it has morphed into something deeper and more integral, both more and less remarkable. I have absorbed the Fairyland adventures so thoroughly that they have become a burbling, familiar background against which select incidents rise up and stand out for the commotion they create in my memory. For the moments in my own life they snap into being. Frank’s outsized appetite is now a tall tale like so many others told and retold at the cabin: Remember the time Chris and Sean caught two trout by bashing them over the head with a paddle?

The ongoing resonance of my grandparents’ original gifts is this contemporary pleasure of inhabiting multiple worlds at once: the tights-and-tunic finery of the prince amid a cascade of surf set alongside the brilliant, refracting surface of the lake, which seeps around the edges of my book; the recalled scratchy orange cushion, skewered by a calcified stray wicker fiber, overlaid with my grandmother’s mock-indignant voice; and, finally, a distant and wondrous Victorian world contemporaneous with the book’s creation, sparked into life by the handwritten names of my female relatives. I feel ecstatically like a living slice of the fossil record, several eras compressed into one vertical stack, beheld and existing simultaneously. Four generations of women reading and rereading and passing on the same sappy, gently humorous stories. The same way in which sleeping in the cabin’s bedrooms—now white and spare and lined with windows, but once upon a time dim and chock-full of international art, polyester clothing, family photos, and drying swimsuits—is like living two lives at once. When we sit for meals inside at the long dining table, on the rare occasions it’s too cold for the screened-in porch, I am also perched at G&G’s round avocado green breakfast table, eating off my special Peter Rabbit plate with the rabbit-handled utensils. When I walk across the hickory floors, I am reminded this is not the way it was in the Ellie-and-Mal era of carpet and linoleum. Far from a painful emotional split, however, this triality of present-past-fiction is a magical enhancement, a gift from a fairy prince.

My fever dissipates on the third day, after the triumphant return of Prince Uno’s son and the imprisonment of the evil sprites. A week later, my husband and father and I visit the Penobscot Narrows Bridge. Here is a new event, a new place, one that does not recall anything of my grandparents or my past in this place. Completed in 2007, the bridge is a massive engineering feat of cable suspension, and hosts a forty-two-story observation tower. It’s a hazy day, so from the top we cannot see as far as Saddleback Mountain, or some of the other peaks a dozen miles in the distance, but we do watch an eagle skim the river’s unruffled surface far below, and I think of the bald eagle and its mate, or sibling, that we watch from the dock, holding our breath as it coasts above or disturbs the air with its massive wings. Then I look downriver, where the Penobscot broadens into the bay, and I notice that the surface of the water is roughed up, coarse like sandpaper. With building apprehension, I see the rough surface spreading toward us, and I point this out to my father: a broad, strong wind is rushing upriver with speed. Though we’re encased in glass and cannot feel any change in atmosphere, the effects are visible, the branches of the trees on the shore beginning to twist and sway, and I have to tell myself to stand my ground. This is how I sometimes feel at the cabin, like I am about to be engulfed by a force I’m both wary of and eager for, because why complicate the present? Why not let the past sit admiringly on the shelf? Why rush into it headlong, feverishly, when new adventures beckon? Because we, like Uncle Frank, are sentimental explorers, and once acquainted with a delicious, mysterious land, we cannot help but return to what was once new and unknown.

—Jennifer Acker

Washington, Maine

Jennifer Acker is editor in chief of The Common.