Photo courtesy of Jesse Gwilliam | Amherst College

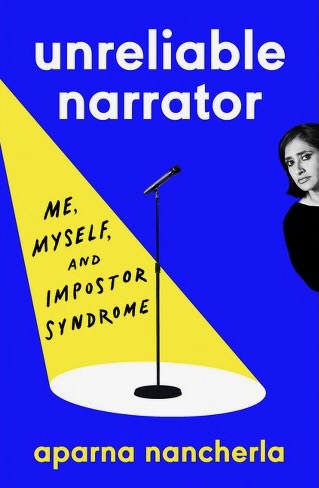

APARNA NANCHERLA is in a class of her own. A writer, comedian, actor, and podcast host, Nancherla returned to her alma mater, Amherst College, for a conversation with The Common’s editor-in-chief, JENNIFER ACKER, during LitFest 2024. The two discussed her diverse creative portfolio, standup as a mode of self-expression, and her newest memoir-in-essays, Unreliable Narrator: Me, Myself, and Imposter Syndrome. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. For a recording of their full conversation and more about LitFest, visit the Amherst College website.

Jennifer Acker: Can you tell us a little bit about imposter syndrome, the role that it’s played in your personal and professional life, and the impetus for the book?

Aparna Nancherla: It’s fair to say self-doubt and I have a long history together. From a young age, being a shy, introverted kid and a first-generation immigrant compounded and made me feel like a fish out of water. I perpetually approached life as an observer on the sidelines—taking in what everyone else was doing, then trying to cobble together my own impression of what was normal. Frequently, imposter syndrome showed up when I was given an opportunity or neared a goal. I would think, “Do I really deserve this? Why was I given this? Am I like everyone else here?” Some people get opportunities and their first thought is, “Finally, you guys took long enough.” For me, I thought, “Why?”

JA: Did it take you a while to identify that it was imposter syndrome, or was that a journey?

AN: I recognized the persistent feeling that I didn’t fit in early on. Once I learned the term, I thought (as anyone with imposter syndrome would), “Okay, even if someone else says they have it, they’re delusional. They’re clearly qualified. I actually am a fraud.”

JA: You write in your book that you thought writing about imposter syndrome might cure you of it, but what actually happened as you were writing this story?

AN: My theory was not salient. I mean, when writing anything personal, you realize you’re gonna face feelings or come into contact with memories that aren’t fully resolved. It was a chest of drawers, and I was like, “Let me just open every door at once; what could go wrong?” It was a lot of struggling with the question of who am I to write a book about imposter syndrome. In the most meta way, I thought, I should turn in a blank book—that would be the most authentic.

I’m also a lifelong perfectionist, and a lot of the writing process was learning to be at peace with the fact that a lot of the essays I wrote didn’t have tidy endings. Or, I started at one point and then I ended at another one, but you weren’t necessarily getting a sense of closure with all of them. Another point of the book was how we are messy as humans, and there isn’t always a tidy resolution to things like our relationships with body image or productivity or the Internet. I wanted to really get into those gray areas, which are harder to speak about with something like standup, where it’s a setup-to-punchline—you’re in and you’re out.

JA: One of the stories that you tell in your book is about how you got your start in comedy through this speech competition. Could you tell us about the competition and the speech classes that you took beforehand?

AN: I was really shy, and as an immigrant kid, my mom was worried I wouldn’t be able to hack it in the world. She kept giving me these confidence-building exercises. One was when we would have pizza as a family every Sunday night, and she would make me order it over the phone. I would be so scared; I would have to psych myself up and be like, “You got this! Veggie lovers, bell pepper, and onion—you’re in the zone.”

Another exercise was public speaking class when I was around 11. It was my sibling and I with a bunch of adults in this very depressing conference center. Every week, we’d be given a topic, and it’d be something like “Here are my thoughts on fruit.” But it taught me how to speak in front of a group.

One of the things it led me to was this speech competition. The topic was, “What is one issue affecting the South Asian community today?” It was through our local temple, and I remember all the other kids went in a serious direction—they talked about racism and being excluded and discrimination and feeling othered. But I decided to go in a humorous direction—I did a take-down of Bollywood movies. It came purely from my resentment of being forced to watch them by my parents. This was before subtitles—they were all pirated—so I never knew what was happening, and apparently there was a lot of built-up anger. So I wrote this speech that was just a full-on roast, and people loved it. I won the competition, and it gave me an inkling that humor has this power to enrapture people in a way that you don’t always get in normal life. Talking in front of a group of people led me to that realization in a way that talking with strangers one-on-one couldn’t.

JA: What did your mom think of the speech?

AN: I think she was like, “I have notes, but fine.”

JA: You’re a self-described introvert; you even hosted this podcast series called “The Introvert’s Survival Guide.” Could you tell us a bit about being an introvert and choosing the stage as a performance mode or a means of expression?

AN: Generally, I’m someone who cannot collect my thoughts in front of other people. I get so anxious about how I’m presenting or being perceived that it’s really hard for me sometimes to feel present when I’m communicating with people I don’t know well in smaller conversations. Comedy and performing allow me to come to the stage prepared with what I want to say and what I want to communicate. It feels like a more controlled environment. I can have a message to tell you, and I’ll know when you’re going to laugh or when I’m going to pause. It’s just more structured, and I think that feels weirdly more manageable than telling a funny story at a dinner party

JA: How has the material of your comedy changed over time? For instance, someone might write their first novel very autobiographically, and then want to change it up and do something different for the second one. Is that true for comedians as well? How do you think your work has changed?

AN: It’s almost the reverse of novelists maybe, because when you’re first writing your routine or experimenting with your voice, you’re leaning more into what the audience is responding to. You’re trying to find that balance between what you think is funny, and what they think is funny. And then as you gain confidence in your voice, you’re then more willing to dive into and write jokes about topics you’re really interested in. You already know how to write a joke, and so you can allow yourself to get more personal and explore topics that might not seem as funny right away.

JA: Do you think your comedy was less personal in the beginning of your career?

AN: It can be a real journey. I remember my first joke being about, like, public restrooms. A few years in, I started talking more about mental health and my own struggles with it, delving more into the areas in my life that were a little darker. I didn’t always know where I was going to come out at the end of the joke.

JA: Do you remember the first times you began talking about mental health in your comedy acts? What did you want to talk about, and what did it feel like?

AN: I mainly struggle with anxiety and depression, and I first started writing about them when I was struggling pretty acutely with both. I was having trouble writing about anything else, so I thought that I might as well figure out how to exploit them, have them do some work for me. I looked up to comedians who have been openly talking about mental health for forever, like Maria Bamford and Gary Gulman and Marc Maron, but I never thought of myself as someone who had something transportive to contribute to the conversation. But then, when I started talking about it on stage, I noticed a connection with the audience that I wasn’t expecting. People recognized it in a way that I was very surprised by, and I think that recognition made me want to keep exploring that area.

JA: What kinds of responses did you get from the audience? Was it something that you noticed in the moment, while you were performing, or did people write to you?

AN: Both. I was very active on Twitter at the time, and so I would write Tweets about it that got a lot of circulation and responses. I noticed a recognition of those experiences. At first, I thought people were like, “Oh my gosh, you’re so brave. You talk about mental health,” but I began feeling it come back around the other way. I started to ask, “Am I commodifying this part of myself for attention, and not because I have something deep to say about this?” It became a snake eating its own tail. And I wanted to use my book to explore that.

JA: I was going to ask you how you wrestled with your conflicted feelings about it.

AN: That’s the interesting thing about being a performer who’s also a standup comic. Most standups are predominantly using their life as the canvas for their writing material, so it can become a little perverse when something bad happens to you. If someone in your family gets sick, you’re wondering how you can make it into a show. It can become a little grim in that sense. I think you are constantly evaluating whether you are ready to talk about this onstage, or whether you’re just trying to make it into material. So when I was writing the book, I took a years-long break from standup and that break gave me a chance to figure out what I actually wanted to say about this. It gave me a chance to reflect and reset with the mental health stuff not just for the sake of attention or clicks or likes.

JA: When you came back to standup, how was the material different? Did you have different rules for yourself about what you would talk about?

AN: I became a lot more intentional about writing work that I was excited about instead of leaning so heavily on the audience’s interests. It’s subtle, but I think when you’re doing sets all the time, or when you’re really immersed in the bubble of comedy, sometimes you can develop a tunnel vision where every set determines how you feel about yourself. I needed to get out of that mindset and realize I’m a person first, then I’m a comedian. It doesn’t define me.

Aparna Nancherla is an LA-based comedian whose stand-up has been seen on late-night television, HBO, Netflix, Comedy Central, and the occasional meme. Among many memorable roles, she’s starred as Grace (overworked HR rep) on Corporate, was the voice of Hollyhock (teenage horse) on BoJack Horseman, and is the voice of Moon (ten-year-old Caucasian boy) on The Great North. Talk about range! Aparna also wrote for and appeared on Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell on FX, and has contributed multiple op-eds to The New York Times. So yeah, she has some strong feelings on things. For example, waterfalls. She can’t get enough of them. I mean, have you seen one? Just gorgeous.

Jennifer Acker is founder and editor in chief of The Common, and author of the debut novel The Limits of the World, a fiction honoree for the Massachusetts Book Award. Her memoir Fatigue is a #1 Amazon bestseller, and her short stories, essays, translations, and reviews have appeared in Oprah Daily, Washington Post, Literary Hub, n+1, and The Yale Review, among other places. Acker has an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars and directs the Literary Publishing Internship and LitFest at Amherst College.