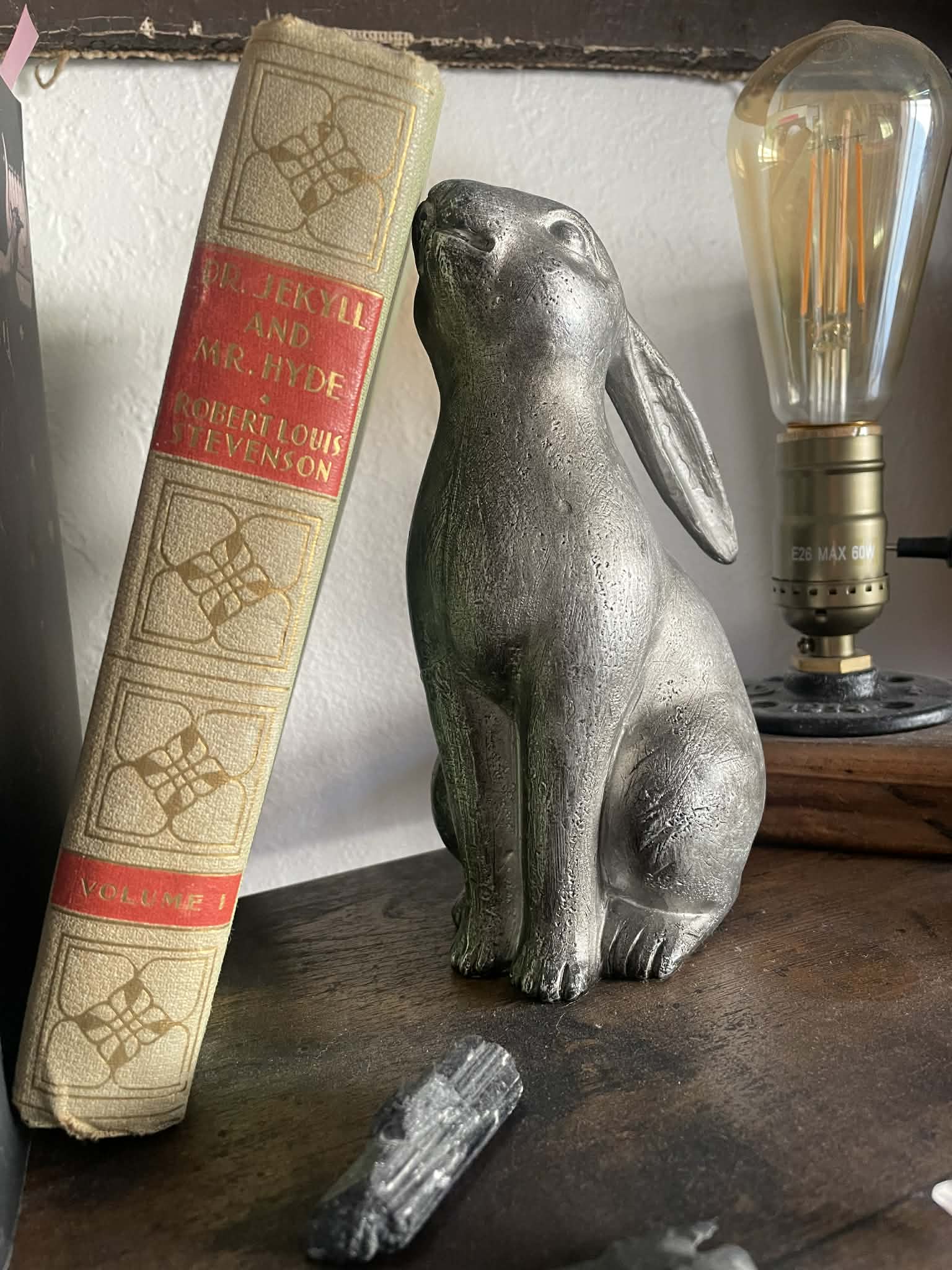

Photo courtesy of author

Herod, Illinois

There are two Gardens of the Gods, but the one in Southern Illinois fit our budget. On the drive down from Iowa City, we listen to podcasts about Norse and Greek mythology to fill the twins’ heads with ideas of magic, with the hope that they might complain less about the hiking. From their car seats, they point out farms with broken corn stalks and a Burger King, making the argument that we must still be in Iowa. Even though we’ve traveled six hours, their six-year-old brains haven’t yet connected time and distance. But I’ve been in the Midwest long enough to know the difference between the farms around a college town and farms around a farming town. And if I wasn’t wisened to it, the signage would teach me soon enough. Traveling through rest stops and restaurants puts us on edge. We make the outline of an average family with a couple of feral kids, if people don’t linger too long in their gaze.

On the day of the hike the twins wake up cranky and reluctant for adventure and will only leave our cabin rental in exchange for marshmallows. They launch an offensive of questions and complaints, filling the car with a foul air like a Victorian miasma getting into my lungs and through the pores of my skin. I pull over at the trailhead for fresh air, slamming my car door shut while the kids shout mama! through muffled glass. While I lean against a tree, my partner takes them out of the car seats and answers questions about where we are and why we stopped, and whether we had, in the course of twenty minutes, ended up back in Iowa City.

When we find the Garden of the Gods, our ruminations transform to awe. Globular rocks rise around us, massive but smooth, making portholes to a vast and distant wilderness. The gods must have been giant children squeezing drip sandcastles from their palms, back when this land was at the edge of a sea. This used to be a mouth, I say. It feels impossible that this peculiar landscape should suddenly emerge among farms and Dairy Queens. We step onto the observation trail dressed for an arduous hike, which is unnecessary because it winds directly from the parking lot. A pregnant woman saunters by wearing a bodycon dress and sandals, sipping from a Chick-fil-a cup.

The rock formations spill into each other and swallow up the people climbing up and through them. One of the twins climbs up a thick pancake-like formation, and the other disappears in a ravine carved out by a river at a time distant from humanity. They both play by cliff edges, and I pretend not to worry. My partner finds a rock to lie on and absorb the sun in their own thoughts. They all relax away from me, feeling safe in their insignificance. I want to pull them back in with a lecture about the carboniferous origins of this landscape, affecting that I can comprehend 300 million years ago. To talk to them about the space between glaciers, instead of letting them hold wonder without inquiry.

The children pour the last of our water over undulating surfaces, remaking ancient rivers. One shouts we are ants, but the idea gets lost against the wind. The sound of gusts and the brightness of the sun remind me of a film I cannot remember except that it had subtitles. Rocks like this glitch the mind and whip the wind through memory. They leave us no narrative to cling to, slowly eroding as we build, against the weather of this country.

Eli Rodriguez Fielder is a queer, Latine writer and artist from Queens, New York, based in Iowa City, Iowa. She is the author ofThe Revolution Will Be Improvised, and her creative non-fiction writing has appeared or is forthcoming inAster(ix), Crossings, The Global South, Voices from the Prairie, Flere, and Brink. Her current work explores the entanglements between anatomy science, medical astrology, and chronic illness.