MELODY NIXON interviews BENJAMIN ANASTAS

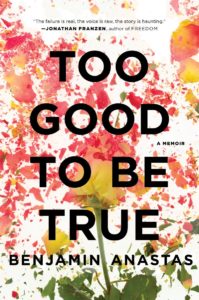

Benjamin Anastas is the author of Too Good to be True, a memoir described by The New York Times as “smart and honest and searching,” and “so plaintive and raw it will leave most writers… with heart palpitations.” He has written two novels, An Underachiever’s Diary, and The Faithful Narrative of a Pastor’s Disappearance, as well as multiple reviews and essays, one of which, “Boys with a Synth,” is published in Issue 06 of The Common. Melody Nixon talked with Anastas about his skepticism for social media, the role of the writer in society, and memoir as fiction’s “whiny and embarrassing stepchild.”

Melody Nixon (MN): You were on Twitter for precisely 1 year, 4 months, and 22 days (I followed you in the spring of 2013, just before you resigned), and then you infamously pulled the plug on both Twitter and your Facebook author page. Your Google + byline is “social media skeptic.” What’s it like being “just a writer” again, now that you’re no longer on those forms of social media?

Benjamin Anastas (BA): I suppose the phrase “just a writer” sounds more Luddite than I’d meant it to. Writers do need to engage with the larger social and technological issues of their time, and I wouldn’t want to be so scornful of social media—the collective experience, that is—that I’d miss out on trying to understand why so many people are hooked on it, what fundamental needs and appetites it inflames as it feeds them.

That said, I do have real issue with the pressure that writers are put under to open a Twitter account and set up a Facebook author page to promote their work. One, it’s a massive time-suck. Two, it doesn’t work. Three, it’s just one more example of the corporate groupthink that gets passed around as wisdom in the publishing industry. Facebook author pages are free, they’re generally set up by the author him or herself, and they come with the false promise of reaching millions of users—but in reality they’re just an online ghetto that Facebook uses to compile ever more content and tempt users into paying fees to “promote” posts about their upcoming readings, reviews, etc. You’d be better off renting a flatbed truck and just throwing copies of your book off the back while someone drives you around in slow circles. Eventually you’d hit a reader with enough room in her tote bag to take one home…

MN: In “Goodbye to Twitter,” an essay for The Daily Beast, you wrote that you abhorred Twitter for the way it promoted “the endless personalizing of events both great and small, the human need to play pundit with the forces that overarch our lives, to feel like we’re participating.” How do those Twitter forces differ from the forces acting on us as writers, the pressures or desire to do the same in our writing?

BA: It’s the participating part that’s different, I think—that is, the illusion of participation—now that we get so much of our news and spend so much of our time online. It’s one thing if you’re in Gaza and you tweet about the whistle of an airstrike, and quite another if you read an article about the airstrike while sitting with your laptop in the back garden and tweet your outrage to the world. Opinions matter, of course. Who doesn’t want to be a responsible global citizen? But the pathway between urge—or sensation, or half-thought—and transmission to a larger audience is so direct now, thanks to Twitter and other forms of social media, that I think we’re just awash in the little burps and twitches of the lizard brain. There’s very little thinking being done—just reacting. And the writer’s job is to think.

MN: One of my favorite former Twitter accounts, the parody Real Kaplan account (@real_kaplan) tweeted that he’d “Bet you $8 Benjamin Anastas is lurking on Twitter right now” the day your essay came out in The Daily Beast. And later that day: “I know you’re there, Benjamin Anastas. I can hear you breathing.” I loved those Tweets because there was such a playfulness to them. At the same time, I admired your resolve on the issue. Was he right? Have you ever been back to look around?

BA: To be honest, I felt so relieved not to be groveling around on Twitter anymore once I left that I haven’t been back to lurk much. Every now and then, when I hear about a really good Twitter fight, I might look up the accounts on Google and read down the feeds—but I feel like Colin Farrell when he goes back to Jamestown after living with the Indians in Terrence Malick’s The New World. He walks through the gate to find the Europeans living in squalor, splashing around in their own filth and fighting over their last scraps of food. The small-mindedness and the self-infatuation that you see so often is why I like to call it Twitter Village.

MN: About your memoir, Too Good to Be True, you wrote: “I’d written a memoir dappled with embarrassments so I already knew what that was like, and I wanted to retain whatever was left of my dignity [by leaving Twitter].” What I find so absorbing about the book, and so illuminating, is its vulnerability. Do you really feel embarrassed about what you wrote in there (or were you just being funny)?

BA: You do have to sacrifice your dignity—or at least your high opinion of yourself—when you write a memoir, and that’s especially true if you want the memoir to be any good. I don’t believe in the absolute value of confession; your first responsibility as a writer is to the page, to make your sentences as artful and convincing and significant as they can be, and after that, maybe you get some points for candor, for upending the myths and misconceptions that our time has given so much currency.

I don’t feel actively embarrassed about the memoir, no. Are there times when I wish I hadn’t had to write it? When the fact that it’s out there has made life more complicated, for myself and for the others who happen to be in it? Admitting that you’re broke in a prominently published memoir and gaining some renown as a writer who’s played his little violin in public has some disadvantages, especially in the age of the Google search. It’s certainly cut down on the assignments I used to get from the more respectable style magazines from time to time. But I stand by the book as a piece of pure writing and as a response to a period in life—we all have them—that left me baffled. I wrote about it because that’s what I do. James Baldwin has a quote somewhere about changing the way that people see reality by a millimeter—if literature can do that much, it can change reality.

I’ve been writing fiction again lately, which has been great on every level. I think I’ve had my fill of reality experiments. At least I’m feeling full now.

MN: You said “the writer’s job is to think.” How does the writer think differently when writing fiction compared to nonfiction?

BA: To be honest, I’m not sure there’s any real difference in the quality of thought when you’re writing fiction and nonfiction. At least when you’re writing seriously and doing it well. One of the books I like to keep within reach—actually, I just looked at the bookshelf nearest to my desk and I have three copies of it, sandwiched betweenLolita and Pale Fire—is Nabokov’s Speak, Memory. It’s definitely, irrefutably a work of nonfiction (it doesn’t hurt that Nabokov’s early life belongs in an epic novel), but everything he describes, both large and small, is summoned to the page in its Platonic form. In one of my favorite sections of the book Nabokov describes a ride he imagines his mother taking through St. Petersburg in a horse-drawn sleigh—he’s home sick in bed, which only expands his powers of perception, and while he’s lying there he can hear the snorting breath of the horse, the “rhythmic clacking” of the horse’s scrotum (my God! What a phrase), the thudding of frozen clumps of dirt and snow against the front of the sleigh. Rightly or wrongly, I think we tend to associate description this vigorous, this tensile, with fiction rather than nonfiction—even if the source material comes from life. Mary Karr would have done away with Nabokov’s polite evasions, like using the word “scrotum,” and written about the horse’s giant, hairy ball-sac.

MN: Yea gads. That’s quite an image. So do you think that fiction is given permission to be more imaginative in its descriptions, more literary and lyrical almost, than nonfiction?

BA: I’m not sure that it’s a matter of permission. You can be as ‘literary’ as you want when you write nonfiction, but ultimately the goal is to serve the real—to capture it in flashes and give it life. I have to admit that I’ve felt a little peeved for the last year or so about the first-world status—the instant respect—granted to fiction that bears an uncanny resemblance to memoir. Fiction often gets the benefit of the doubt, I think, no matter how much it reads like the artful transcription of life, while memoir remains almost suspect by definition—literature’s whiny and embarrassing stepchild. I’ve really enjoyed the Karl Ove Knausgaard that I’ve read (I’m sort of marooned in the later stages of My Struggle: Book Two at the moment), and Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04is next up on my bedside. But really—if they called it “memoir,” do you think that everyone would be losing their heads over it? No: they’d be questioning the entire enterprise. I admire both writers tremendously, especially for how they’re claiming reality for their fiction and letting us see the world right under our noses again—but just because it’s called a “novel” doesn’t mean that it’s any more artfully composed than nonfiction or memoir. It’s just not bound to the facts of a life.

MN: I’m writing a memoir, and the process is hell because I feel like everyday I write I have to confront all of myself, my own defense mechanisms, insecurities, rampant demons, before I can get to the page. Your memoir presents a real delving into your psychology, beyond the degree of most narrative memoirs. You even write about trying to get help through therapy (and running away from therapy), in a very memorable chapter. How did you deal with having to confront so much of yourself in every writing session?

BA: I really felt like I was writing a novel the entire time. Maybe it’s my background as a fiction writer, and the fact that I logged my 10,000 hours, when I was younger, writing only stories and novels; still, when I sat down to describe the Park Slope therapist with her rings of curls and the bandage on her forehead, or the psychic healer in the West Village who told me to make up little lists and burn them, it wasn’t me who inhabited those scenes. It was me the protagonist. I was a character. I was St. Augustine back when he was stealing pears and wasting them—or going to the coliseum with Alypius to watch the Roman games. It was me when I knew less, when I was still lost. I hadn’t learned anything at all.

MN: How much have you, the protagonist, learned by the end of the memoir? I felt you resisted the typical “and then I figured my life out and everything became amazing” sort of narrative resolution we’re offered by many traditional memoirs.

BA: The memoir definitely doesn’t end with a wedding, or a neatly symmetrical book auction that nets me a $1 million advance. The biggest reason, of course, is that neither of those storybook outcomes happened; but I also wanted the book to end on an unresolved note because it felt like the most authentic ending to me for any book that isolates one period of a life and examines it for deeper meaning, tries to read it for signs and portents like my Greek grandmother used to do with coffee grounds. From the beginning, once I realized that my notebook entries could turn out to be a book, I saw Too Good to Be True as a kind of extended footnote that was happening in tandem with the story as it unfolded. Of course, I was living the story out—I had no idea how things would resolve with my girlfriend, my writing life, my money crisis—so any ending I chose for the memoir would have to be provisional. Once my writing career is done and all of the books are lined up on the shelf, I expect that unresolved endings are going to be a common thread. An Underachiever’s Diary just stops, almost in midstream; The Faithful Narrative of a Pastor’s Disappearance never solves its animating mystery; the memoir closes while I’m working as a fact-checker and avoids tying up all of its narrative threads. I’m always looking for forms of resolution that treat the story as an ongoing proposition—that it will continue on somehow once the book is finished.

MN: Your essay, “Boys with a Synth,” published in Issue 06 of The Common, explores your early experiments with music-making and the new freedom of being a boy earning money, at the beginning of adulthood,“heading into the unknown.” The scenes you sketch have such precise detail. Some details though, you phrase as questions. When writing personal nonfiction, how much do you allow yourself to“fill in?” Do you have a hardline about what level of detail must be verifiable/completely accurate?

BA: I’d say that I’m 85% scrupulous. I recently read a memoir by the Spanish writer Marcos Giralt Torrente, titled Father and Son: a Lifetime in English (it’s Tiempo de Vida in Spanish), that takes a much harder line—there’s very little in the way of dialogue, no fake names or identity disguises; scenes in the distant past are hardly ever dramatized. It’s a wonderful book, and Giralt Torrente is a writer who I’m going to keep on reading as long as he’s translated (I don’t read Spanish)—still, the bargain I make with memoir is a different one. Of course I don’t have perfect recall of events from the near or distant past, particularly when it comes to speech and dialogue. I think it’s only fair that I try and mask the identity of some people in the book, especially when they ask me to. Legal issues come into play. As do ethical ones—I’m intensely aware, as the child of a novelist and memoirist myself, that it’s just not that fun to be written about. Still, I do it anyway. I do allow myself a little leeway to invent, but only when it comes to irrecoverable things like dialogue, and only if I am writing a scene or about a situation that is rooted in fact. Or at least in a memory.

MN: Memory and place are interwoven in the essay, and your memoir too gives a strong sense of place—particularly the Brooklyn neighborhood you live in. How does place influence your writing today, especially as someone who moves regularly between two states (New York and Vermont)?

BA: It’s true, I’ve become something of a displaced person since I joined the literature faculty at Bennington College. I spend about half the week at an experimental school surrounded by green that can feel like it’s suspended on a cloud; the rest of the week I’m in a borough (Brooklyn) that’s become an advertisement for itself. One of the things I tried to do in the memoir was describe how strange it felt to watch a neighborhood—I lived in Clinton Hill then—transforming itself before my eyes, to be at a place in life where I found I had no market value while rent and the value of brownstones were skyrocketing. I used to walk around during the day since I had nothing but time and pass the buildings being rehabbed, the film crews taking over a block for shooting, look up from my reverie of failure to see a double-decker tour bus packed with gawkers lurching past. I was in the scene but not in-step with it. I felt like Bartelby after he’d been sacked, or a secret agent for Occupy. It was a desperate time, and I don’t want to minimize that, but it also reified my belief—and I don’t use the word ‘belief’ lightly—that the writer’s job, at least one part of it, is to stand apart, to question the value and utility of the things the world cherishes. That meant I wasted a lot of time muttering to myself about long brunch lines clogging the sidewalks on weekends, the ubiquity of the $30 scented candles. It’s not a coincidence, I think, that the printed word is in decline while brunch is in a Gilded Age. Everything is about over-the-top indulgence now, and print requires discipline.

MN: You mentioned you’re back to working on fiction now. Any plans to write a dystopian social media novel, perhaps set in Twitter Village?

BA: That’s a great idea for a novel, actually. If I didn’t already have my hands full with teaching and writing projects already begun I might steal it from you. I’m one of those superstitious types who never talks about things that aren’t finished—it breaks the spell—but the next book is going to be entirely in keeping with the books that came before and a total surprise. It has to be. There’s no other way to write.

*

Benjamin Anastas’ essay “Boys with a Synth” appears in Issue 06 of The Common.

*

Melody Nixon, a New Zealand-born writer living in New York City, is the Interviews Editor for The Common.

Photo credits: Headshot by Elizabeth White; “Sky over Clinton Hill” by Benjamin Anastas.