from Pessoa: A Biography

The following chapter from Pessoa: A Biography, forthcoming from Norton/Liveright, tells the story of how Alberto Caeiro, Fernando Pessoa’s first major heteronym, came into existence. The other full-fledged heteronyms, Álvaro de Campos and Ricardo Reis, would emerge three months later. (The heteronyms, Pessoa claimed, were not mere pseudonyms, since they thought and felt and wrote differently from their creator.) Although he had published some critical essays and a passage from The Book of Disquiet, Pessoa was still virtually unknown as a poet. Literature, moreover, was not Pessoa’s only interest. Throughout his adult life, he wrote prolifically about philosophy, religion, psychology, and politics.

The story of Caeiro is preceded by a brief sketch of the political climate in Europe before World War I, especially in Portugal, where, less than four years earlier, a revolution had toppled a much–discredited monarchy, replacing it with a tumultuous republic.

For this publication in The Common, I have excluded most of the notes of the book version (bibliographical information, mainly) while adding other notes to clarify references to people and events mentioned in earlier chapters.

—R. Z.

For Pessoa it would prove to be an annus mirabilis, but the early months of 1914 already portended catastrophe for Portugal and the rest of Europe. Lisboners were not especially fazed by the train strike in January that led to clashes on the streets and a few deaths—serial disruptions had become the new normal—but the Portuguese Republic, now in its fourth year, felt increasingly fragile. Afonso Costa and his Democrats, the most radical of the three republican parties, had managed to stay in power throughout 1913, but to do so they not only had to quash another monarchist revolt, they also had to put down insurgent republicans disenchanted with the Democrats for not being radical enough. So overcrowded were the jails with political dissidents that British newspapers, always quick to find fault with postmonarchical Portugal, launched a campaign denouncing their appalling conditions. In order to more efficiently mete out justice to their opponents, the Democrats had created a rogue police force called the Formiga Branca, or White Ants, and soon there was a second vigilante force, the Black Ants, which wielded arms on behalf of a different republican faction. Pessoa must have marveled at the sad coincidence: when he was a little boy, his Uncle Cunha[1] had made up fantastical stories about warring ants, beetles, and crickets, and now gun-toting “ants” were terrorizing the streets of Lisbon.

Political volatility had spread over most of the continent. In neighboring Spain, the assassination of a Liberal prime minister, in November 1912, further fragmented its political system, so that neither of the major parties could command a majority on its own. Governments in France were forming and dissolving in quick succession, with three prime ministers resigning in 1913 alone. Great Britain was being rattled by worker strikes, suffragette activism and the threat of armed violence in Ireland over the question of Home Rule. And the governing elite in Germany was anxiously trying to curb the rise of the far-left Social Democrats, who had won the Reichstag election of 1912. The arms race between Europe’s major powers continued unabated, and even certain smaller countries, particularly in the Balkans, were spending huge sums of borrowed money to outfit their armies with the latest and best in modern weaponry.

But while it is easy, with hindsight, to point to the many warning signs of the First World War, there was no climate of anticipation, no sense among the vast majority of people that the balance of power known as the Concert of Europe was actually a tinderbox waiting to explode. Europe’s restlessness, deriving not only from national rivalries but also from a more empowered working class, was a sign of vitality as well as a source of instability, and local economies were prospering. Portugal was no exception. Construction there was booming, export revenue from cork and wine was increasing, and so was the demand for imported goods. Industrialization continued to lag, however, and the balance of payments deteriorated.

Afonso Costa’s high-handed style of governing and his unwillingness to entertain changes to the harsh anticlerical laws had alienated moderate republicans, forcing him to resign in late January of 1914.[2] This could only have delighted Pessoa, who detested Costa, but he was temporarily distracted from the national drama, with literature now occupying most of his attention. Lusitania, the largely political magazine he had sketched plans for in 1911, had evolved into a would-be monthly magazine devoted entirely to creative writing. Mário de Sá-Carneiro drew up a masthead and a table of contents for the first issue, scheduled for publication on March 1, 1914. Pessoa was to be the editor-in-chief, with Sá-Carneiro, Armando Côrtes-Rodrigues, and Alfredo Guisado rounding out the editorial staff,[3] but the new Lusitania, like the old one, foundered even before it could be launched. In February, on the other hand, Pessoa, at long last, went public as a poet. Two of his poems, including “Swamps,” appeared in an ephemeral magazine under the suggestive title Twilight Impressions.

Both Sá-Carneiro and Alfredo Guisado were enthusiasts of the Swampist style, but Pessoa himself was growing weary of the decadent languor that saturated poems such as “Swamps,” certain prose texts for The Book of Disquiet, and “static dramas” like The Mariner.[4] About the final version of this play, published in 1915, he would boast: “No more remote thing exists in literature. Maeterlinck’s best nebulosity and subtlety is coarse and carnal by comparison.” Having succeeded in being more nebulous than Maeterlinck, more ethereal than Pascoaes[5] and more syntactically and imagistically exotic than Sá-Carneiro, Pessoa longed to do something else. He would wade no more in the stagnant waters of Swampism, and static drama, by its very definition, had nowhere to go, which is why Maeterlinck himself soon abandoned the genre. There are marvelous passages of dialogue in Pessoa’s other static dramas, which include a play aptly titled Inertia (Inércia) and Salomé, influenced by Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, but none have the dramatic power and magic of The Mariner, which was the only one he was able to finish.

The Mariner is a brilliant demonstration of how to use dreams like bricks to construct reality. Ensconced in a circular castle, three women keep watch through the night over the corpse of a fourth woman, dressed in white and lying in a coffin. They hesitantly talk, uncertain what their talking is for or whether their words stand for anything real. The dead woman represents their future, or their true present state, or perhaps she is the God people have stopped believing in, or the author at the end of his resources. Or perhaps she is not dead, just sleeping, and the three watchers are but the diaphanous substance of her dreaming. All logic, all discourse, and all speculation prove to be circular, like the castle. But halfway through the play, one of the watchers begins to tell her dream about a shipwrecked mariner stranded on a desert isle where, all alone, it pained him to remember the life and the people he once knew. Rather than succumbing to nostalgia, he spends his days conjuring up a completely new and unfamiliar homeland, slowly filling it with dreamed streets, events, and people. And so vivid is this past built only of dreams that it comes to replace the life he had actually lived before being shipwrecked.

After telling her strange tale, the watching woman wonders if the mariner might after all be the only one who is real, and the scene in the castle with her and her companions just one of his dreams. One dream inhabits another, reality is at a loss, and the circle keeps on circling.

Pessoa had the vexing habit, for scholars and biographers, of assigning fictional dates to some of his works, usually for the sake of an ideal narrative of his life and literary development. When he published The Mariner, in 1915, he dated it October 11–12, 1913, even though his notes and surviving manuscripts suggest that the initial draft was not completed until January or February of 1914, and we know it was much revised before it saw print. But Pessoa wanted to make sure that his future readers and commentators read his static drama as the prelude to a far more radical drama of the soul, which began to unfold in March 1914. The Mariner ends with the crowing of a rooster and the first light of morning chasing away the night of dreams. The new morning belonged to a different kind of dream, which thrived on sunlight and had a name: Alberto Caeiro.

Fernando Pessoa in January 1914, two months before the “birth” of Alberto Caeiro.

Twenty-one years later, in his letter to a young critic about the origins of the major heteronyms, Pessoa would explain that Alberto Caeiro began as a joke he wanted to play on Mário de Sá-Carneiro. The idea was to invent “a rather complicated bucolic poet” and to dress him up with a few biographical details, to see if he could fool his friend.

I spent a few days trying in vain to envision this poet. One day when I’d finally given up—it was March 8, 1914—I walked over to a high chest of drawers, took a sheet of paper, and began to write standing up, as I do whenever I can. And I wrote thirty-some poems at one go, in a kind of ecstasy I’m unable to describe. It was the triumphal day of my life, and I can never have another one like it. I began with a title, The Keeper of Sheep. This was followed by the appearance in me of someone whom I instantly named Alberto Caeiro. Excuse the absurdity of this statement: my master had appeared in me.

In 1936, the year after Pessoa died, his letter was published by its recipient, Adolfo Casais Monteiro, and the myth of the Triumphal Day was born. For decades to come, almost no one doubted the story of how Alberto Caeiro, the “master,” erupted in Pessoa’s soul with a torrent of wondrous poems on March 8, 1914.

Only toward the end of the twentieth century did a thorough examination of Pessoa’s archives reveal a rather different literary genesis. The oldest Caeiro manuscript—a large, folded sheet of paper with five poems from The Keeper of Sheep —is dated March 4, 1914. Another folded sheet, dated March 7, contains three more poems from the same cycle. The name of Alberto Caeiro is missing from these two manuscripts and may not have occurred to Pessoa until a few days later. More poems followed, on manuscripts with and without dates, and by mid-March Pessoa had written at least half of the forty-nine poems from The Keeper of Sheep. He mythologized his achievement, crunching the work of ten days or two weeks into just one momentous day, March 8. But whatever the time span of this first outpouring of Caeiro poems, it was a triumph such as Pessoa had never experienced—not because of the quantity of poems written but because of what they said and how they said it.

Here are some of the lines of verse that came to him on March 4, like a sunbeam slicing through clouds of metaphysics and hitting him right in the eyes:

For the only hidden meaning of things

Is that they have no hidden meaning.

It’s the strangest thing of all,

Stranger than all poets’ dreams

And all philosophers’ thoughts,

That things are really what they seem to be

And there’s nothing to understand.

Yes, this is what my senses learned on their own:

Things have no meaning: they have existence.

Things are the only hidden meaning of things.

Lines like these seemed to fatally discredit all the theories and explanations Pessoa had accumulated through many years of study and reading. To see things as they are, asserts a Caeiro poem written on March 13, requires “lessons in unlearning,” and if Caeiro taught Pessoa anything, it was the art of unlearning, of seeing as if for the first time. Consider the sixth poem from The Keeper of Sheep, which neatly dispenses with the age-old debate about God’s existence:

To think about God is to disobey God,

Since God wanted us not to know him,

Which is why he didn’t reveal himself to us…

Let’s be simple and calm,

Like the trees and streams,

And God will love us, making us

Us even as the trees are trees

And the streams are streams,

And will give us greenness in the spring, which is its season,

And a river to go to when we end…

And he’ll give us nothing more, since to give us more would make us less us.

Whether or not God exists, according to Caeiro’s pellucid logic, is entirely beside the point of what life is for, namely living. Though indifferent to God, it is with holy devotion that Caeiro exalts the trees, the streams, and all of Nature, leading Pessoa to define him at one point as “an atheist St. Francis of Assisi.” Caeiro was not a true atheist, let alone a saint. He was, however, a religion, whose first and main adherent was Fernando Pessoa.

Pessoa claimed, in The Book of Disquiet, that certain fictional characters were more real to him than living people. Alberto Caeiro was just such a character. Only in succeeding years would Pessoa describe this heteronym’s physical features—medium height, hunched shoulders, fair hair, blue eyes—and elaborate a biographical sketch: born in Lisbon on April 16, 1889, attended only primary school, lived in the countryside with an elderly aunt, and died from tuberculosis in 1915. But the voice and personality of the clear-seeing shepherd, who never actually kept sheep—“But it’s as if I kept them,” he says at the beginning of The Keeper of Sheep—already stood out in his earliest poems, which could not have originated without that voice, that personality, and that vision, so completely unlike Fernando Pessoa’s.

In a letter sent to João Gaspar Simões6 in 1933, Pessoa would call The Keeper of Sheep “the best thing I’ve ever written,” an achievement he could never again match, since it exceeded what he was rationally capable of creating. Pessoa did not write these words only for the sake of the myth that would survive him; they were an admission of his own stupefaction and feeling of insufficiency. In March 1914, Alberto Caeiro, uttering verses as clear and natural as water flowing down a slope, was nothing less than a revelation, one that Pessoa could never fully fathom. And so the story of his Triumphal Day was not so much a fabrication as it was a metaphor.

Pessoa did like to play tricks, however, and Alberto Caeiro was perfect material for indulging his mischievous tendencies. In the past he had sent letters signed by Charles Robert Anon, Faustino Antunes, and Alexander Search to newspapers, publishers, business firms, and even—in the case of Antunes, his heteronymous psychiatrist—to people he had known personally in Durban.[7] The emergence of his new, far more extraordinary heteronym emboldened him to go further. With a perfectly straight face, he told some of his café companions about this unheard-of poet named Caeiro who lived in Galicia, on the other side of Portugal’s northern border, and he showed them copies of poems from The Keeper of Sheep that had come into his hands. His closest literary friends—Sá-Carneiro, Côrtes-Rodrigues, and Alfred Guisado—knew the secret and swore to keep it a secret, but António Ferro and others were fed the hoax and swallowed it whole.[8] So authentic was Caeiro’s voice, and so different from Pessoa’s, that it was easy to be fooled.

Ferro was a test case. Pessoa’s real ambition was to fool the world at large, by launching Caeiro as an independent poet, while he remained backstage, out of sight. Caeiro a literary immortal and himself a complete unknown—that, for Pessoa, would be the highest triumph. He could never have dreamed anything like that for Alexander Search, who was not psychologically or even biographically all that different from his maker and whose poetry was good, but not great.[9]

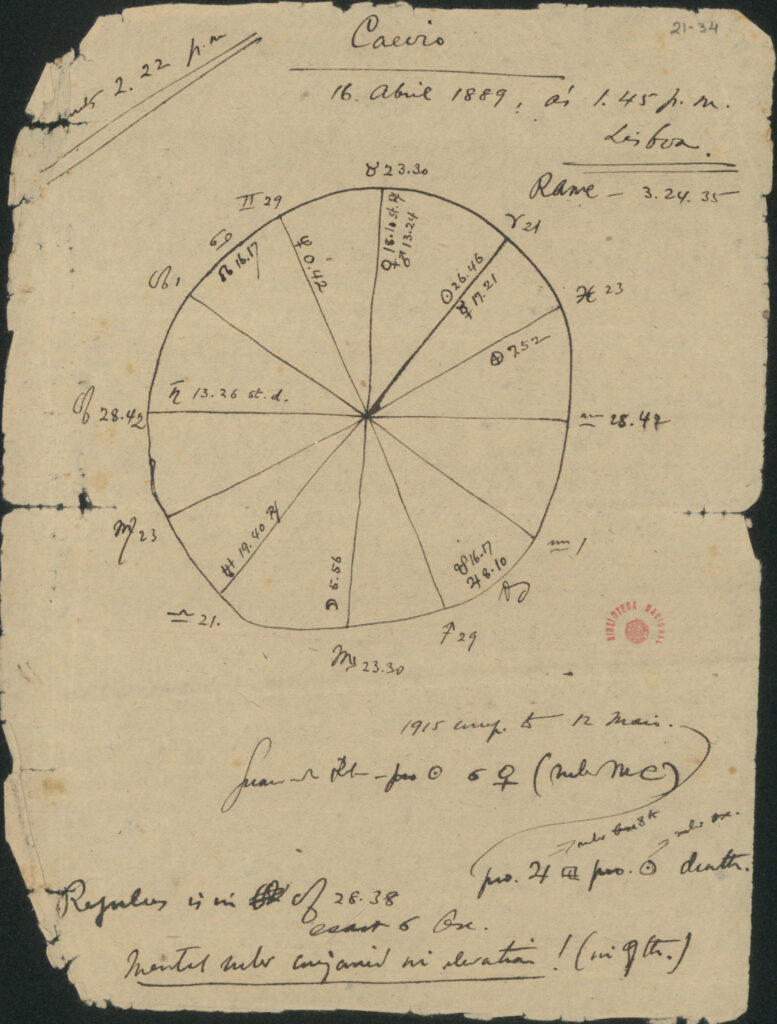

Pessoa cast astrological charts for himself, for friends, for famous people, and for his heteronyms. Image from Pessoa’s archive, courtesy of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

As poems streamed forth in the stunningly clear voice and simple language of Caeiro, Pessoa simultaneously began writing critical prose texts to announce the new literary prodigy. The poetry and the criticism sometimes occupied the same manuscript sheets. On March 13, while sitting at a café table, Pessoa jotted down the first version of the Caeiro poem that begins: “What we see of things are the things.” After eight lines had been written, an English critic abruptly took control of Pessoa’s ink pen and wrote the following incomplete sentence: “At the same time a preciseness so astonishing in noting states of enjoyment of nature that it is difficult ….” Pessoa was already brainstorming for the preface to Caeiro’s complete poems in English. Thomas Crosse, as the heteronymous translator assigned to the task would eventually be called, never translated more than a few lines of poetry, but many pages were written for his Translator’s Preface and for articles about Caeiro that Pessoa hoped to publish in British newspapers.

The plans to promote Caeiro were extravagant: translations of his poetry into French as well as English; articles about him and his work in English publications such as T. P.’s Weekly and Athenaeum, in Mercure de France, in Spanish, Italian, and German publications; and a blitz in the Portuguese press. Pessoa thought of asking some journalists he knew from Lisbon’s cafés to help publicize the new poet, and he counted on Sá-Carneiro to write an in-depth article for O Século, Portugal’s best-selling daily paper; on Alfredo Guisado to write for a newspaper in Galicia; and on Côrtes-Rodrigues to report on Caeiro in the Azores. In the end he decided not to impose on his friends, but he himself drafted an impressive array of promotional materials, including an interview with Caeiro allegedly conducted in the Galician port city of Vigo by someone who used the initials “A. S.,” which perhaps stood for the English heteronym Alexander Search. The interview was in Portuguese, however. At one point the interviewee alluded to his “spontaneous materialism,” but when asked point-blank if he was a materialist, Caeiro replied:

I’m not a materialist or a deist or anything else. I’m a man who one day opened the window and discovered this crucial fact: Nature exists. I saw that the trees, the rivers and the stones are things that truly exist. No one had ever thought about this.

Caeiro thought about a lot of things. Or rather, there was a lot of thought behind his “spontaneous” perception and acceptance of things as they are. Pessoa pointed this out in the rough draft of an article he was preparing for A Águia, the Porto magazine that had so far been willing to publish whatever he cared to submit. Although it had the air of being naturally materialistic, he argued that Caeiro’s work—“calculated, measured, contemplated,”—was essentially abstract. His materialism, far from being a direct and spontaneous appreciation of things, was a philosophical view of the world, and the Nature he celebrated in his verses was an idea of Nature. This philosophizing and abstracting capacity, wrote Pessoa the critic, was precisely what he admired in this new poetry. The revelation of Caeiro was for him a poetic revelation. Caeiro did not open Pessoa’s eyes to a new way to live life; he represented a new way to engage with life in his writing.

“Nothing is born from nothing,” wrote Lucretius, and Caeiro’s birth owed something to Lucretius himself. The Roman Epicurean’s De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) used poetry to expound a materialistic philosophy of the world, and Caeiro’s poetry was a kind of repeat performance on a more modest scale, despite the heteronym’s claim to eschew philosophy. Lucretius may not have been at the front of Pessoa’s mind when he dreamed up Caeiro, but the connection he drew between the two poets in his notes was quite real. His knowledge of classical literature and philosophy was not only vast, it was vivid, it pulsed in his intellect, and its influence touched most of his work, whether signed by his own name or one of his literary alter egos.

Walt Whitman was the most visible as well as the most intimate influence on Caeiro. The most visible, since the heteronym’s poetry adopted the American’s free-verse style, took up some of the same topics, and employed some suspiciously similar turns of phrase. The most intimate, since Whitman taught Caeiro how to open up, feel everything, be everything, and sing. The audacity of Whitman’s poetic “I” had awed Pessoa when he read “Song of Myself” for the first time, six or seven years earlier, but he had no inkling of how to write like that. Alberto Caeiro showed him how.

In his many pages of criticism to promote the new, bucolic heteronym, Pessoa repeatedly mentioned Walt Whitman, at times falsely claiming that his influence was minimal or nonexistent. And he marshalled arguments, mostly in English, to prove how fundamentally different Caeiro was. Whereas Whitman strove to see an object deeply, linking it up “with many others, with the soul and the Universe and God,” Caeiro merely wanted to see the object clearly and in itself, apart from other objects and free of “transcendental meanings.” Pessoa also contrasted Whitman’s “violent democratic feeling” with “Caeiro’s abhorrence of any sort of humanitarianism.” And there were other differences, some of which Pessoa gathered into a long list. It was a perfectly valid list; the two poets are indeed very different from each other. But Caeiro could never have existed without Whitman, the catalysing inspiration that mixed with Pessoa’s vast poetic culture to set off an admirably productive explosion.

Caeiro’s poetry mentions only one Portuguese writer by name: Cesário Verde, Portugal’s most original poet from the nineteenth century. Scarcely known during his short life—he died of tuberculosis in 1886, at the age of thirty-one—Verde was still not widely read or appreciated in Pessoa’s day. Pessoa read what was available, a posthumous collection called The Book of Cesário Verde, which crammed an astonishing quantity of visual, audible, palpable, and olfactory things into rhyming lines of regular, metered verse. It looked like traditional poetry but read like nothing ever done before in Portugal, or anywhere else in Europe. Here are two stanzas (in my unrhymed translation) from his greatest poem, “The Feeling of a Westerner”:

An aproned knife maker, working the lathe,

Redhotly wields his blacksmith’s hammer;

And bread, still warm, from the baker’s oven

Sends forth its honest, wholesome smell.

And I, whose goal is a book that galls,

Want it to come from inspecting what’s real.

Boutiques shine with the latest fashions;

A street urchin gapes at their window displays.

The other forty-two stanzas from the poem, whose narrator strolls through the city of Lisbon as the day turns into night, are similarly packed with urban and human detail: streetcars, carriages, apartment houses, churches, a jail, bars, a brothel, stevedores, fishwives, beggars….

There is a Baudelairean influence in Verde, but without the ostentatious decadence and individualism of the French flâneur, who actively cultivated his reputation as a bourgeois-despising bohemian. The Portuguese poet, who was meekness personified, quietly working in the family business by day, gave his poetic soul to the life and objects all around him. “Oh, if I’d never die! If forever / I’d seek and attain the perfection of things!” he longingly wishes in “The Feeling of a Westerner.” His passionate objectivity is what made him a vital secondary spark for igniting the turbulent mélange of erudition and creative energy in Pessoa that gave rise to Alberto Caeiro. Walt Whitman provided the model of an expansive narrator that respected no boundaries and obeyed no rules. Cesário Verde contributed his thoroughly objective vision of things—of things intensely felt, and not only things from the city. Half of his poems were set in the rural outskirts of Lisbon, where the family had a farm.

It was in the countryside northeast of Lisbon that Alberto Caeiro lived in a white house. There, leaning out the window in the late afternoon, we find him reading The Book of Cesário Verde at the beginning of the third poem in The Keeper of Sheep, and so intently does he read that his eyes burn. The twenty-eighth poem from the same cycle also begins with him reading a book, this time by an unnamed “mystic poet,” but he quits after two pages, laughing so hard that he cries. From comments made elsewhere, we know that the mystic poet alluded to was Teixeira de Pascoaes, for whom Nature was the glorious pageant of a spiritual dimension.[10] Caeiro criticized him and other mystic poets—including St. Francis of Assisi—for saying “that flowers feel / And that stones have souls / And that rivers are filled with rapture in the moonlight.”

“Caeiro perhaps derives from Pascoaes,” Pessoa admitted in a note written in Portuguese, “but he derives through opposition, through reaction.” One sees this in the early Caeiro manuscripts. With their half-finished poems, crossed-out poems, and poems littered with deletions, insertions, and alternate wordings, they resemble battlefields, with Walt Whitman and Cesário Verde waging war against Pascoaes and St. Francis of Assisi. The conceits and language of the latter team are the ones consistently defeated—sometimes by being modified and incorporated. Unlike the horrific conflict that would soon engulf Europe, it was a quick and brilliantly fruitful war, lasting for just a week in March 1914. Out of this showdown between contrasting poetic tendencies emerged, serene, Alberto Caeiro.

A reaction against Pascoaes, Caeiro was also and more broadly a reaction against Fernando Pessoa—against all his learning and incessant intellectual wrangling. Pessoa explains this beautifully in the unfinished article about the pseudoshepherd that he drafted for Pascoaes’s magazine, A Águia. Feigning “complete ignorance about the person of Sr. Alberto Caeiro,” the article writer surmises that in his youth he must have been exposed to a “vast literary culture,” after which “he retreats to the country and there, completely giving up all reading and book learning, surrenders himself to nature.” Or, as Caeiro puts it, in two lines from a poem:

I lie down in the grass

And forget all I was taught.

He forgets it, but he would not be the poet Alberto Caeiro without all that prior learning.

The first person to translate Caeiro into English in a sustained way—twelve poems—was Thomas Merton (1915–1968), the American Trappist monk who was himself a fine poet as well as a major writer of contemplative literature. He studied Eastern mystical traditions, noting their connections with Western mysticism (St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Ávila, Meister Eckhart…), and felt especially, personally drawn to Zen Buddhism. It was their “Zen-like immediacy” that attracted him to Caeiro’s poems, which he first read in Octavio Paz’s Spanish translations. He perceptively noted, however, that this Zennishness was “sometimes complicated by a certain note of self-conscious and programmatic insistence.”[11]

In 1914 Zen Buddhism had still not been popularized in the West, and Pessoa’s knowledge of it was scant, though he was interested in the tenets and spirit of Buddhism generally. Caeiro’s likeness to Zen was a sheer coincidence, evident in his renunciation of studious learning and the preconceptions it fosters, in his commitment to seeing what is there to see, without interpretation, and in his distrust of metaphysical speculation. One scholar has even noted similaries between Caeiro’s verses and Japanese poetic styles such as the haiku, dear to many followers of Zen.[12] The principal aim of Zen, which is satori, or enlightenment, was not an ambition of Caeiro, who had no ambitions, but his accidentally Zennish qualities are what made him the master of the two other major heteronyms soon to emerge—Álvaro de Campos and Ricardo Reis—and of Fernando Pessoa himself. What’s more, the story of Caeiro’s mastership makes for yet another point in common with Zen Buddhism, whose essence is properly transmitted through the direct example of and dialogue with a master rather than through private study and devotion.

Pessoa was the first one to admit the absurdity of claiming that Caeiro was his master, but the claim may seem not so absurd if we think of Caeiro as a convergence of empowering poetic influences that, dawning on Pessoa all at once, changed him forever. In fact the mythical, metaphorical Triumphal Day of Pessoa’s life was not only about the birth of Alberto Caeiro but also about his own rebirth. Pessoa’s account of what happened on March 8, 1914, only partly quoted at the beginning of this chapter, does not end with the appearance in him of Alberto Caeiro. He goes on to say that, after dashing off thirty-odd poems in the name and style of “master” Caeiro, he

grabbed a fresh sheet of paper and wrote, again all at once, the six poems that make up “Slanting Rain,” by Fernando Pessoa. All at once and with total concentration… It was the return of Fernando Pessoa as Alberto Caeiro to Fernando Pessoa himself. Or rather, it was the reaction of Fernando Pessoa against his nonexistence as Alberto Caeiro.

Álvaro de Campos, in his delightful and frequently poignant “Notes for the Memory of My Master Caeiro,” written between 1930 and 1932, recounted a different version of events for March 8, 1914. On that day, Caeiro, who happened to be in Lisbon, supposedly met Pessoa and recited some of his poems from The Keeper of Sheep. Pessoa, reeling from “the spiritual shock” of that encounter, went home and immediately wrote the six poems of “Slanting Rain.”[13] They were his reaction “to the Great Vaccine—the vaccine against the stupidity of the intelligent.” Campos claimed that, because of the inoculating effect of Caeiro, which somewhat counteracted Pessoa’s “overwrought intelligence,” all the poems he would write from then on would be different from the ones he wrote before meeting Caeiro. Campos, it must be said, exaggerated the effect of Caeiro on the poetry signed by Pessoa himself, several of whose finest poems were written before Caeiro burst onto the scene. On the other hand, the triumphal emergence of Caeiro greatly boosted the creator’s confidence to be himself as well as several other personalities and to take to a new level the stylistic experiments that had commenced with “Swamps” and other writings of similar ilk.

Swampism had borrowed a preexisting aesthetic—the Symbolism developed by French poets such as Mallarmé, Verlaine, and Gustave Kahn—and intensified it, making it even more mysteriously suggestive, more excruciatingly atmospheric. The poems of “Slanting Rain,” a bolder experiment, were an exemplary demonstration of Intersectionism, a literary aesthetic theorized by Pessoa in the second half of February, shortly before Alberto Caeiro came into existence.

The new movement was initially little more than an extension and rebranding of Swampism. The other poets of Pessoa’s inner circle—Sá-Carneiro, Armando Côrtes-Rodrigues, and Alfredo Guisado—immediately signed on to Intersectionism but continued to write in their usual style. Meanwhile, the name of the magazine that the four friends were planning to launch was changed from Lusitania to the more cosmopolitan-sounding Europa. At the end of February, Pessoa drew up a list of Intersectionist works that included, right at the top, his “In the Forest of Estrangement” (from The Book of Disquiet), previously considered a typical example of Swampism. The Mariner and his “Beyond-God” sequence of five poems also made the list. So did various short stories of Sá-Carneiro, along with his novel, Lúcio’s Confession. Côrtes-Rodrigues and Guisado were listed for their poetry, as were Mallarmé and Gustave Kahn. In each case the type of intersection was indicated: reality intersected with dreaming, reality with madness, mystery with sensation, the visual image with the musical image, and so forth.

These after-the-fact Intersectionist designations, if not always forced, were at any rate so-whattish. Don’t virtually all literary works depend on conflicting or contrasting elements? To suddenly call those elements “intersecting” is hardly illuminating, let alone a real innovation, as Pessoa was the first to recognize. And so, with his matchless capacity for custom-building whatever was needed, he wrote “Slanting Rain,” which instantly made Intersectionism a meaningful term, a kind of literary equivalent to Cubism in the visual arts. The six poems in the sequence juxtapose scenes from different times and places with each other as well as with the narrator’s differing moods. And the scenes and moods are not only juxtaposed, they also interpenetrate, passing through each other the way Superman passes through walls, without him or the walls losing their structural integrity. In the first of the six poems, which intersects the narrator’s “dream of an infinite port” with a wooded landscape, ships leaving the port “pass through the trunks of the trees” and “drop their moorings through the leaves one by one.” In the last poem of the sextet, the scene and music of an orchestral concert crisscross, without distorting, the narrator’s memory of playing ball in the backyard as a child. The four poems in between play out other sorts of intersections—spatial, temporal, and psychological.

Álvaro de Campos would rate “Slanting Rain” as the most admirable thing ever written by Pessoa under his own name, but most readers are less enthusiastic. Pessoa himself must have had his doubts, since he produced only a small handful of additional works based on the new technique. As for Pessoa’s friends, none was capable of writing anything like “Slanting Rain,” and so the theoretical distinction between Swampism and Intersectionism, although they understood it well enough, was never reflected in their work. The upshot was that, for the next several years, the two movements coexisted, or rather, they were more or less the same movement. Intersectionism became practically a synonym for Swampism.

There was a third –ism, which would eventually absorb and outlive the other two: Sensationism. This aesthetic creed held that sensations, since our entire notion of reality depends on them, should be the basis and the focus of all artistic creation. It was on the back of a sheet of paper with two Caeiro poems that Pessoa jotted down his first ideas about “Sensacionismo,” and Alberto Caeiro was the first Sensationist. He defined himself, and his Sensationist attitude, in the ninth poem of The Keeper of Sheep:

I’m a keeper of sheep.

The sheep are my thoughts

And each thought a sensation.

I think with my eyes and my ears

And with my hands and feet

And with my nose and mouth.

To think a flower is to see and smell it,

And to eat a fruit is to know its meaning.

As the virtual shepherd tended Zen-like reflections such as these in fields of proliferating manuscripts, Fernando Pessoa kept writing promotional texts about him and the literary movements he was going to spearhead, if all went well. The plan was to launch peaceful, pastoral Alberto Caeiro at the forefront of a literary revolution.

The next chapter of the biography tells how Caeiro, instead of evolving into a Futurist poet, ended up giving birth to Álvaro de Campos, an urbane dandy whose first poem, “Triumphal Ode,” was a hymn to machines, speed, modern things, and the big city. Soon enough, as Germany invaded Luxembourg and Belgium, Campos’s poetic energy would be channeled into his “Martial Ode,” which describes the horror of “real war / With its reality of people who really die.”

Footnotes:

[1] Pessoa’s great-aunt Maria and great-uncle Cunha, who had no children of their own, were like a second set of parents when he was a little boy. Uncle Cunha made up vivid, ongoing stories about make-believe politicians and battling arthropods, no doubt inspiring young Fernando to invent imaginary companions.

[2] Portugal’s republicans, after their successful revolution (October 5, 1910), had split into three rival parties, which continually squabbled. Afonso Costa, an ardent secularist, was the leader of the most radical of the three parties.

[3] The poet and fiction writer Mário de Sá-Carneiro (1890–1916) was Pessoa’s best friend and closest literary collaborator. Together with the poets Armando Côrtes-Rodrigues (1891–1971) and Alfredo Guisado (1891–1975), they planned to launch a literary review, which would finally come out in 1915 under the title Orpheu. In 1916 Sá-Carneiro, an exuberant but anguished individual, would dramatically end his life.

[4] The poem “Swamps,” written in the spring of 1913, gave its name to a literary movement known as Swampism (Paulismo, in Portuguese), which may be defined as an exacerbated Symbolism, with sugges- tion, uncertainty, and mystery enveloping extravagant images in a shadowy world without time or geo- graphy. “Static drama” was a term coined by the Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949), whose early plays were practically devoid of action.

[5] The poet Teixeira de Pascoaes (1877–1952) promoted saudade—intense longing and nostalgia—as a uniquely Portuguese, mystical energy that could regenerate the nation. Pessoa had been an enthusiastic but ambiguous supporter of Pascoaes’s ideas.

[6] This literary critic and magazine editor would write the first biography of Pessoa (1950).

[7] Pessoa (1888–1935) was born and died in Lisbon but spent nine years of his childhood—and received most of his schooling—in Durban, the largest city in what was then the English colony of Natal, in South Africa. Until age twenty, Pessoa wrote almost all of his poetry in English, a language he would continue to use, along with Portuguese, thoughout the rest of his life.

[8] Ferro (1895–1956) was a younger member of the literary circle that gravitated around Pessoa and Sá-Carneiro.

[9] Pessoa wrote over a hundred poems in the name of Alexander Search, his most important English-lan- guage heteronym, active between 1906 and 1910.

[10] Pascoaes is described in a previous note.

[11] In New Directions in Prose and Poetry, 19, 1966.

[12] Leyla Perrone-Moisés, in “Caeiro Zen,” Fernando Pessoa: aquém do eu, além do outro (São Paulo:

Martins Fontes, 2011; first ed. 1982).

[13] Published in the second and last issue of Orpheu, in 1915. Pessoa and his friend Sá-Carneiro were the magazine’s editors-in-chief.

Excerpted from Pessoa: A Biography. Copyright (c) 2021 by Richard Zenith. To be published by Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Richard Zenith who lives in Portugal, is responsible for many editions of poetry and prose by Fernando Pessoa, including Livro do desassossego. His translations from Pessoa’s work include Fernando Pessoa & Co.: Selected Poems, A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems, and The Book of Disquiet. He has also translated poetry by Luís de Camões, Sophia de Mello Breyner, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, and many living poets. He spent more than ten years researching and writing Pessoa: A Biography.