By KURT CASWELL

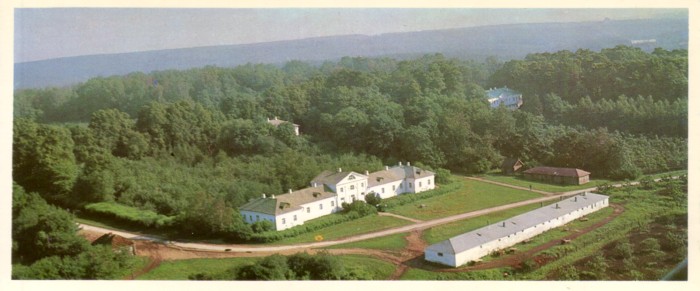

Right now in heaven, Tolstoy is playing with his dumbbells, even those little rounded weights he kept in his study at Yasnaya Polyana have come up with him into the cloud-city of the afterlife. In the spring of 2016, I toured his old house and the estate on which he lived, walked out through the green trees and the precision mosquitoes to his burial mound, a grass covered box-shaped hill on the ground where the great man went in. But why was he great, when so much of his life was spent—that little account of time we all bank on—in little rooms sitting in a chair made for children, propped up on a pillow, his waning eyesight pulling his face in ever closer to the page? After he died, he left the estate and some big books to say he’d lived, but did he live, working over his little pages all day through the sharp Russian winters, his beard dropped down to his belt? I imagine him in the later hours of the day stepping out onto the exposed porch to pump his little dumbbells, raise his hands on his scrawny arms so weighted in cranking out the little curls. His biceps were the better for it, no doubt, maybe his stamina too, and then a long walk through the aching wood with his cane, the top of which folded out to make a little seat on which he rested. He would have listened to the birds and the winds and trees in the wind and birds while sitting on his little chair, an old man, frail and hairy, and still winking at the girls. Perhaps it is enough, winking and making paragraphs on a page and walking in the woods after working with the dumbbells. Perhaps, but great or not, a man cannot bank on bringing up his dumbbells into the afterlife. He has only this one life to own himself, this one road to walk, and all he can do is walk it.

Kurt Caswell’s newest book is Getting to Grey Owl: Journeys on Four Continents. He teaches writing and literature in the Honors College at Texas Tech University.

Photo Courtesy of into-russia.co.uk