Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.

—Elizabeth Bennett Pride and Prejudice

Nobody wants to hear about your trip.

—Amherst College Professor of English Theodore Baird

We don’t travel as a couple anymore, Bill and I, except for the shortest jaunts to Boston maybe once a year, in the summer to the Adirondacks to visit Bill’s brother and family, and to the Berkshires, where friends sometimes take us to indoor concerts at Tanglewood (Bill doesn’t listen to music outdoors). So I travel on my own, but more and more rarely: day trips with a friend, twice-yearly visits to Oregon to keep in touch with son Will and family, once a year or so to the Washington, D.C., area to see my sister, rare overnights to New York. I also dig in more closely here at home—not as closely as Bill does with his piles of books and constant reviewing and teaching at Amherst College, but still, closely.

I walk, usually with the dog, and enjoy the local scene, one that changes with every quirk in the weather, time of day, seasonal decoration, home improvement, and new retail shop. I make small alterations in the routes we take—one day more sidewalk, another day more woods, more open fields. The dog has become unreliable about returning to me when called, so I keep her on leash most of the time. I find pleasure in my regular routine, which varies enough to keep me grounded. I’m not as restless as I once was, it seems, not so much yearning to travel or take part in more cultural activities, not so much yearning of any sort. Unlike the dog, I no longer ache to break through fences. My daily round seems to be enough. That includes reading and writing (until recently I wrote a monthly column for the local paper, where I had earlier been an editor), volunteering at the local hospice, playing tennis, going to yoga, and spending time with a refugee from Nepal who wants to improve her spoken English. These are the fixed points in my week. I cook a meal almost every evening, do the laundry, care for the garden, watch the finances, see that the household is kept up physically. It feels like a good life.

For my parents—my father born in Budapest in 1895, my mother in Vienna in 1907—travel was an expression of their wish to see the world, but also of their status as cultured, leisured people, with enough disposable income to spend on nonnecessities. Married in Budapest in 1931, they went on their honeymoon to Italy and to the Dalmatian coast of Croatia. They had a car with a chauffeur, stayed in good hotels, ate well. In the photo albums I have of the first years of their marriage, there are many shots of monuments and churches, of my mother, always fashionably dressed, standing in front of one or another of these locations.

After they—we: my parents, my sister, and I—came to the U.S. in 1939, just ahead of the outbreak of World War II, my parents traveled little. As “enemy aliens”—Hungary had become an ally of Germany—they couldn’t easily leave the country. There was no going to Europe until after the war, and they had little interest in getting to know the States. Besides, there was gas rationing. They had settled in Scarsdale, New York, on the recommendation of a friend, an educator who vouched for the public schools there. During the war they vacationed at Lakewood, a comfortable resort in Skowhegan, Maine, where there was a summer theater and a congenial artists’ colony. When the war was over, they returned to Europe, but they avoided Central Europe until the early 1960s, when they made a brief visit to Austria and Hungary. My father was reluctant to return to his home country, which was now under Communist rule. No family members remained there; all had emigrated or perished. But my mother wanted, as she said, “to draw a line under it.”

The experience was unpleasant. People were remote and formal. My father was convinced that their hotel room was bugged, and perhaps it was. The line my mother wanted was drawn, hard and fast. My parents never went back to Hungary after that, and I heard my father speak about it only once, when he was quite old. “It was a beautiful country,” he said, and there were tears in his eyes.

Bill’s and my travel pattern has contracted noticeably in both range and frequency as the years have gone by. Between 1964 and 1974, we and our sons spent three separate sabbatical years abroad: Rome once, and London twice. For quite a few years afterward, Bill and I traveled together in the summer, back to England, back to Italy, and then to France, where I wanted to follow the fatal trajectory of my Austrian grandfather, who died there at the hands of the Nazis in 1943.

Then, about a dozen years ago, Bill decided he did not want to travel anymore. I see the decision beginning with a diagnosis and treatment for prostate cancer in 2000, which put him in touch with his mortality in a new way. He was also beginning to have trouble with his back—not excruciating, but steady, chronic discomfort. Sitting in a car or an airplane for long periods was, to put it mildly, no fun. All of this appeared to concentrate his mind. From here on, he seemed to say, he would spend his time and energy reading, writing, and teaching, listening to music and enjoying the meals in his kitchen, with me and sometimes with friends and family. No longer willing to drive to Boston to attend the basketball games in the now impossibly loud and expensive Garden, he would watch on TV as the Celtics’ fortunes rose and fell. He would enjoy visits from his sons and grandchildren, staying home to keep our corgi company while I periodically went to visit them and sometimes ventured even farther afield.

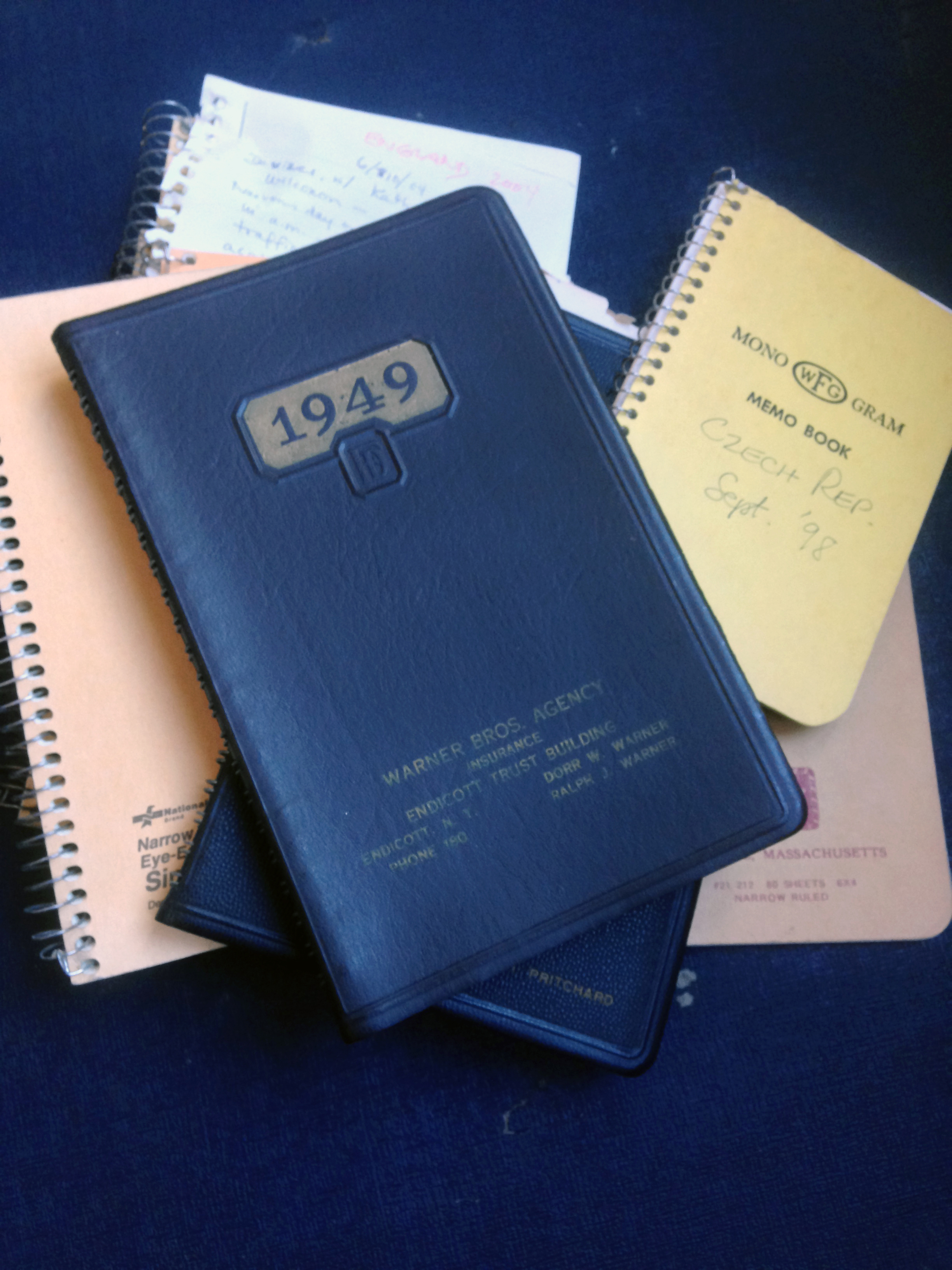

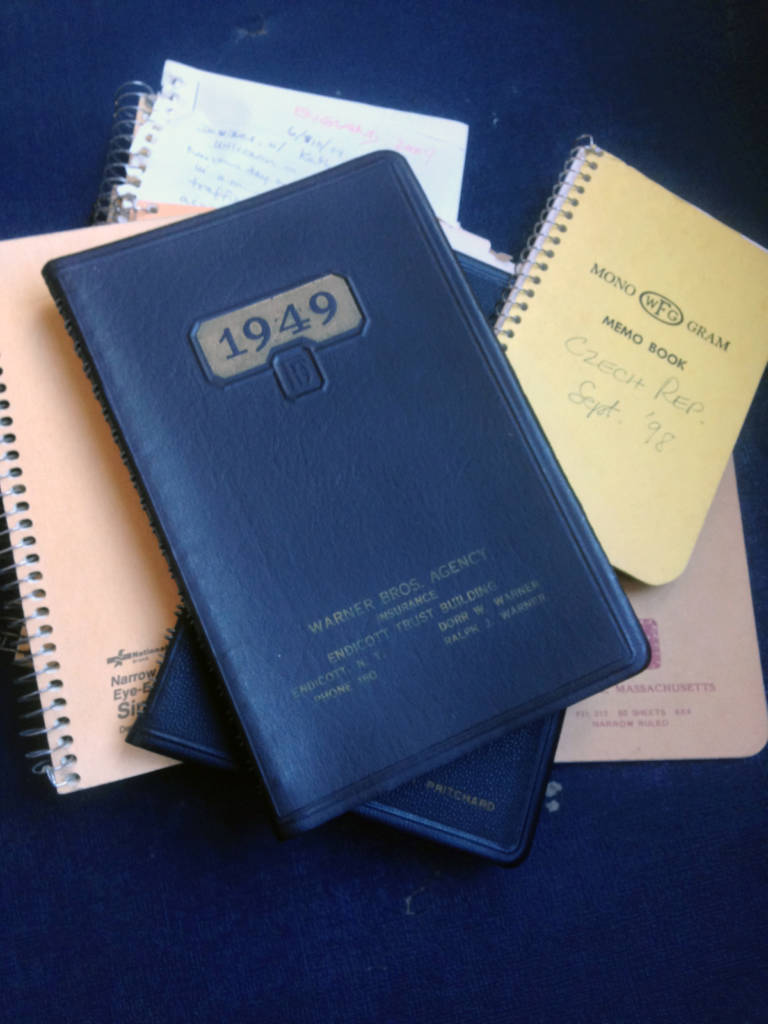

Recently, in an effort to get straight about our mutual and separate timelines (“What was the year we stayed in that funny inn in Cromer on the North Sea?”), Bill handed me the typed journals he’s kept of some of his and our travels over the years. I have kept my own journals, and the records we wrote separately of our travels have come to represent for me not only accounts of our varied, often shared experiences, but also, in some larger way, our points of similarity and difference. I see them in combination as a portrait—a collage, a mosaic, a diptych—of our sixty-year-plus marriage.

What happens when two people live together for decades? Over time, it seems to me, some differences get worn away while some remain like old scars that ache when it rains. All marriages are mixed marriages, I once asserted, and almost all battles can be boiled down to the irritable question: “Why can’t you be more like me?” On the other hand, if one is lucky, there is the balm of affection and shared interests. In addition, there is the huge volume of shared experience, private jokes, catchphrases. Bill and I can finish each other’s sentences, anticipate each other’s responses. Great satisfaction can be found in this lifelong dance, this not always graceful pas de deux.

Bill and I married in 1957, when he was twenty-four and I was twenty, and took a little wedding trip that included a couple of Northeastern sites: a stop in the Adirondacks, where his family had vacationed early in his life, and then a few days at the excruciatingly elaborate wedding of some friends. The following summer we rented a house on an island off the coast of Maine. It was isolated and beautiful. In what would become a typical division of labor, Bill brought his typewriter to work on his doctoral thesis, and I explored the island, learned to cook the mussels that grew on the rocks, swam—in brief, heroic spurts—in the frigid waters, and did a lot of reading. My mother, who visited at one point, remarked that this vacation would result in either a divorce or a pregnancy. (Neither of these happened, although I did get pregnant the following year.)

Bill and I married in 1957, when he was twenty-four and I was twenty, and took a little wedding trip that included a couple of Northeastern sites: a stop in the Adirondacks, where his family had vacationed early in his life, and then a few days at the excruciatingly elaborate wedding of some friends. The following summer we rented a house on an island off the coast of Maine. It was isolated and beautiful. In what would become a typical division of labor, Bill brought his typewriter to work on his doctoral thesis, and I explored the island, learned to cook the mussels that grew on the rocks, swam—in brief, heroic spurts—in the frigid waters, and did a lot of reading. My mother, who visited at one point, remarked that this vacation would result in either a divorce or a pregnancy. (Neither of these happened, although I did get pregnant the following year.)

The first of our big trips was a sabbatical year in Rome, 1963–64. We had two sons by then, ages three and eight months. I had been to Italy once before, with my parents as a teenager, sullen and resentful of having to be with them, yet enjoying the country and testing my new knowledge of Italian art after a year in college. I was not a good traveling companion, since I was in a perpetual battle with my mother. Our sabbatical in Rome had none of the luxury of the time I spent there with my parents—no five-star hotels or meals in fancy restaurants. After all, we were living on a young academic’s salary and had two very young children. Still, we were comfortable enough in an apartment sublet from friends of friends. Those friends had been persuasive about how much pleasure they’d had in Rome with their small children. Other friends who had spent the previous year in England had been equally persuasive. I did not experience that pleasure. Instead, the year was a struggle to survive as a parent and a wife. I was not good at making use of the people who could have made things easier—a couple of British au pairs, one after another, and an Italian housekeeper who came with the apartment. I was young and not used to asking other people to do things for me. It was all pre–women’s movement, and I likewise did not know how to ask my husband for help, much less an equal share of the work. So I tried to do it all, and was angry and miserable. While I learned to shop and cook and keep house in Italian, to make my way to the laundromat and the Montessori nursery school, to deal with the plumber and the apartment’s leering porter, Bill went to his desk at the American Academy during the day and worked on his book on Wyndham Lewis or else educated himself about the art and architecture of the city. It was, as I later came to describe it to myself, a matter of his doing art while I did life. One friend, a single man, a full-fledged fellow and resident at the American Academy, said to me, disapprovingly, apropos of my lack of acquaintance with important monuments: “You don’t know where you are.” And he was surely right from his standpoint, that of a classics scholar who was being well looked after and had no domestic responsibilities. The accusation stung, and still stings. I was a bad tourist, a preoccupied visitor, not seeing what I was supposed to see.

Bill’s father, a lawyer for the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company in Johnson City, New York, had two weeks of vacation every year. His mother, a music supervisor in the public schools, had the schoolteacher’s long summer vacation, but funds were tight. From 1936 to 1949, that time was devoted to a family stay at Rocky Point Inn, a comfortable, full-service resort on Fourth Lake in the Adirondacks where they could enjoy three meals a day and the company of similar families. There was swimming (though Bill never really learned this, to my sorrow), tennis, hiking, boating, a pool table, and ping-pong. Bill, a budding pianist, was encouraged to perform for an appreciative audience from a young age. Aside from that two-week sojourn, his father, a difficult and deeply dissatisfied man, truly had no interest in travel, although he agreed, toward the end of his too-short life, to go with his wife to the Canadian west, where they visited Banff and Lake Louise. Bill’s mother, a woman of boundless energy into extreme old age, had, by contrast, always wanted to see the world. After retiring, she went on tours that took her around the world, touching many of the most famous tourist spots, registering her approval or disapproval of them, much as she did for everything in the rest of her life.

Bill had been to Europe in 1951 as a college student, traveling with a jazz band that was hired to entertain troops. But although they performed in many spots, from Frankfurt and Vienna to Casablanca and Rabat, they were there to make music, not to see the sights. When he and I and our two very small children got to Rome in 1963, he was ready to learn about the place. The Blue Guide became his bible, and he followed its instructions and often quoted its severe opinions: “A not very impressive ravine” was one of our favorites. This habit of consulting guidebooks continued through our next two sabbatical tours, both of them in London, where Pevsner’s architectural observations became his new source of truth. I was usually the one seeing oddities not necessarily in the guidebook. “Look!” I was often exhorting him—and still do at times—as he kept and keeps his nose planted firmly in the guidebook or some other volume.

So, what do I know now about how to travel with Bill? I know that no matter how long or short the trip, when we arrive at our destination, he will immediately want to take a nap. Meanwhile, I will want to go out and walk. This is as true for a morning’s drive to New York City or Boston as it is for an overnight flight to London or Rome. We go our separate ways on arrival and reconvene later. We have learned to do the same in museums—look at the clock and set a time to meet up, then wander freely or together as seems best.

Sometimes, in a new place, the traveler may encounter the comforting sensation of contentment, of feeling at home. In the book about my family, Among Strangers, I describe an occasion when someone I barely knew asked me whether, although I’d lived in Amherst for most of my life, I’d ever felt really at home somewhere.

“Yes,” I said, “on the plains of Hungary.” And as I said it, it felt right, even though I’d never put it just that way before. The Great Hungarian Plain, the Alföld or puszta, begins in Budapest, just east of the Danube, as soon as you cross one of the many bridges connecting the green hills of Buda with the flat bustling center of Pest. Keep heading east and the land stays flat, the sky huge. Go east another 100 kilometers and you will reach Hungary’s other major river, the Tisza, an often muddy, sluggish stream that runs roughly parallel to the Danube before joining it in the former Yugoslavia. You will have passed through some of the richest land on our planet, flat and fertile, a dark, alluvial soil capable of growing almost anything….

In 1991, I had headed out this way with my husband. As I exclaimed over the beauties of the landscape, Bill hunched further down behind the steering wheel, resisting my efforts to include him in my quest for family footprints. He was not moved by the red-tile-roofed villages or the acres of vineyards, nor the rows of poplars lining the small country roads. He was not enjoying the hot sun and the flatness. He was not amused when we had to wait most of an hour on a dusty riverbank to put our rented car on a rickety raft-like ferry to take us across the Tisza River.

Later, I decided that feeling at home may be a little like falling in love, both of them connected to precipitous and distinct sensations, both dangerously tinged with myth, cliché, and longing.

Bill, unlike me, has had all the roots he ever needed or wanted in his upstate New York upbringing, so he never quite understood my need to search for mine. But that didn’t fully account for his reluctance and irritability in the Hungarian countryside. He was not being a good sport, not being a Boy Scout, in contrast with my attempts to roll with the punches, expect the unexpected. His spirit of adventure was distinctly limited. This was not fun! It made him anxious, and he was not going to conceal it.

Our journals were where we recorded both joys and irritations for ourselves. We did not, that I can remember, talk about keeping our respective chronicles, nor did we anticipate publishing them. In this particular linked account, of a cross-country train trip, I have been able to frame the story my way. Bill would surely have done it quite differently.

In April of 1990, Bill and I boarded a train in Springfield, Massachusetts, and headed to the West Coast. We stopped overnight in a few places both there and back, shown around by former students of Bill’s as well as by some older friends. It was a trip of three weeks, one of our longest times away from home except for our sabbaticals.

As Bill and I wrote about our experience, our accounts converged and diverged in often predictable and, I think, amusing ways. Bill’s journal is typed—typically, since writing by hand is not comfortable for him. In 1990 he was typing on an IBM Selectric, as he had for years and as he continues to do even now, although in the past few years he has converted to a computer for the final copies of his essays and reviews. Did he keep notes of our three-week sojourn? He doesn’t think so. He wrote it all down after we returned. I am impressed, as always, by his capacity for recall, his detailed remembrance of names, places, and events—especially meals—past. My own recollections are recorded contemporaneously in spiral-bound notebooks

Here is how Bill’s account of that trip west begins:

Sunday, April 8: Springfield, Mass., to Albany, N.Y.

The problem was how to get through this day (without a Celtics game) until train departure time at 7:40 p.m. This was somehow managed, and David picked us up, took us to the station (providing useful help with heavy suitcases, not soon again to be available—the help, that is).

I am aware here already of Bill’s steady sense of the possibilities of loss (the Celtics) and difficulties (lugging suitcases in the absence of a sturdy son). Bill’s stance toward the world and his life has always reminded me of a Housman poem, one of many pieces of poetry he has introduced me to:

I to my perils

Of cheat and charmer

Came clad in armour

By stars benign.

Hope lies to mortals

And most believe her

But man’s deceiver

Was never mine.

The thoughts of others

Were light and fleeting,

Of lovers’ meeting

Or luck or fame.

Mine were of Trouble,

And mine were steady,

So I was ready

When Trouble came.

Well, of course he wasn’t always ready when trouble came. His motto was not the Boy Scouts’ “Be Prepared”; rather he was always anticipating difficulties—accentuating the negative, you might say—but without anticipating a solution. He was Eeyore in Winnie-the-Pooh, or the pessimist in the old joke about the optimist and the pessimist: Parents have two sons. One is always happy and cheerful; the other is just the opposite, always gloomy. How are they to understand this? A psychiatrist gives them a test. He puts the pessimist in a room full of brand–new toys and games, and after a while he comes in to find the boy weeping bitterly. “What’s the matter?” asks the shrink. “Oh,” says the boy, “these things are wonderful, but they’re going to get old and break and the pieces will get lost.” The psychiatrist then visits the optimist, whom he’s put in a room full of horse manure. The little boy is laughing and happily tossing the stuff up in the air. What’s the explanation? “With all this shit,” says the little boy, “there must be a pony in here somewhere.”

Bill will insist that this tendency toward the dark side reflects his perspective as a satirist, and when it’s amusing I can see his point, but it can also be just plain irritating. My own stance is the less amusing one of the problem–solver: What can I do about this? Which is not to say that I don’t complain, but usually after I’m done doing that, I try to see if the problem can be solved, and if it can’t, I usually try to shut up and turn my attention elsewhere.

But the next few sentences in Bill’s journal turn his attention to the plus side:

The expected feeling of relief on plunking ourselves down in an agreeably spacy and not yet odorous coach seat was nonetheless welcome, even though predicted. Better yet, we had followed Bill Kennick’s [Amherst College colleague in the philosophy department] instructions about not eating supper till on the train. Since there’s no diner between Springfield and Albany, we were prepared with a Picnic Supper, ham and chicken sandwiches following martini drunk from brother Craig’s silver cup (or so I term it). It was dark, there was nothing to look at, so we blundered along happily on the first leg of things. Sometime after 11 p.m., we disgorged at the Albany (actually Rensselaer) station, spanking new, and waited for placement on the Lake Shore Limited…. We were eventually placed in what is known euphemistically as a Slumber Coach, in the intricacies of which we were instructed by the most interesting Train Attendant encountered on the trip. This was Dick Holt, a retired dentist, who, after thirty years, so he said, of not being sued by patients, decided it was time for a new career. His aspirations are to procure a place on the Chicago-to-west-coast Zephyr.

In my journal I note that our dentist/attendant gives us tips on where to sit, including to position ourselves on the right when crossing the Mississippi in order to see the whole train turning. We take his advice.

We arrive in Chicago after a restless night, but before that, Bill is cheered by the hearty breakfast.

Nothing brings things round like breakfast. Amtrak breakfasts, as well as their other meals, turned out to be first-rate: nicely done eggs, good breakfast “meats” (bacon and sausage), even grits a couple of times on the more southern routes. Lunch, which is a free-for-all (one makes reservations for dinner) was less appealing, but equipped with Vouchers (our food having been paid for in advance, as it were), it was pleasant not to think about prices and just dig in.

An important aspect of train dining is that you are seated—almost invariably, since the train is usually crowded, as this first one was—opposite another couple, so there is more or less the obligation to make conversation: Where are you headed, where do you live, is this your first trip, etc. Marietta’s absolute willingness to engage in such conversation made it easier on me, who could be counted upon, nonetheless, to produce the occasional monosyllabic grunt of assent.

In Chicago, we visit friends, attend to culture, and do some eating, as my journal notes.

Tuesday is free at the Art Institute, so full of people—a fine place. Exhibits of Chicago architecture—Sullivan and Wright. Also plenty of excellent Impressionists. Just getting started on Old Masters when it’s time to go to Berghoff’s for lunch. (Bill’s favorite place.)

Splendid, fast, all-male service in dark downstairs section of this heavy German place—sauerbraten, pork loin, sausages, potato pancakes, creamed spinach, beer. Service in about 8 minutes. Helen [Bill’s former student] gets us to the station after a few misses. Crammed waiting room. First-class waiting room not much better, but all service and announcements very efficient, well-handled.

Then we get on board and continue westward.

We ride in royal splendor in our Deluxe Sleeper across Illinois and Missouri into Iowa. Beautiful open farmland, black soil recently plowed, little towns meet the railroad. Amazing expanse—flat, endless, sparsely settled. Occasional big farmhouses with trees looking like oases in a fertile desert. The sun goes down and a big moon comes up over the not-quite heartland. Hungarian [I am studying the language and have brought books with me] a pleasant diversion, but I hate to do it when there’s a view. Also P. D. James. I sit in the coach after dinner because it’s too crowded for two to read and write in our compartment once the beds are down.

Reading and writing is what Bill and I do a lot of in the rest of our lives, when we’re not eating or sleeping. I have a longer list of other things I do, but for Bill, along with teaching, music, and watching his favorite sports teams, this is his life. His 2015 collection of essays and reviews is titled, appropriately, Writing to Live. Other people might worry about what clothing to pack for a trip. He mainly concentrates on what books to bring.

Reading is not easy aboard Amtrak [he writes on April 10, in his section titled “Chicago to the Wilds of Iowa”], and I think not because I’ve selected the wrong books to bring along. I had been warned both by my mother and Theodore Baird [former teacher, now colleague and friend] not to overequip myself with reading matter, but to look out the window. But it seems fair to disregard the advice after dark. Tonight, however, I did poorly at holding my eyes on the correct line of type as the train jounced about. I brought along the most irrelevant titles: a late Trollope, Mr. Scarborough’s Family; Howells’s A Hazard of New Fortunes; P. D. James’s Innocent Blood; and Johnson’s Lives of the Poets. We’ll see what happens.

Wednesday, April 11: Iowa to Salt Lake City

Yesterday’s crossing, before dusk, of the Mississippi into Burlington, Iowa, was interesting because the Iowa town was nicely un-Iowan, hilly, rather old-fashioned and dark in construction, plenty of trees. This morning Marietta reported that, when she looked out during the night, it was snowing in Omaha. That’s all we have to say about Nebraska. When we woke early, we were just east of Denver, in a truly godforsaken part of Colorado, very bad badlands with nothing except mean soil, used cars, falling-down shacks. Very grim Americana. We got off the train at Denver, which seemed slightly unreal as a town, just plunked down there somehow, walked six blocks or so away from, then back to the station. (We were instructed not to leave the station precincts, but daringly disobeyed.)

This would be unquestionably the great scenery day, following the Colorado River for much of it, through the gorges, then coming into Utah and the red rocks. Amtrak’s strongest selling point, this section.

So that was Bill’s description of the scenery. Mine was more detailed:

From Denver—where fog and clouds obscure the mountains—the train climbs slowly up the east side of the Rockies. Ice coats needles of Ponderosa pines, snow first in patches, then more snow. Frequent tunnels, switchbacks with great views. No wildlife all day, except cows later on (not so wild), though we were promised elk and “jackalope.” Then back down the other side as we follow the path of the Colorado River for many miles. Spectacular canyons, some red rock with grainy layers like some immense piece of pastry, some gray and rounded, like animal forms, or even anthropomorphic. Small settlements along river suggest old mining communities, log-sided houses. One huge piece of highway being built along river—said to be the most expensive ever. Territory flattens out as we reach Utah. Near Thompson (a stop), we sit for 1½ hours while a freight train on our tracks works out a coupling problem. As the sun sets in a fine show of silver and pink on the “book cliffs” on one side, open bare range on the other, a fast-moving black cloud passes through, moves on. We’re late coming in at Salt Lake, and it’s half past midnight when a slightly boozy cab driver takes us to the Little America, where we fall into the immense round tub and big white bed.

As I look back from a vantage of almost thirty years, I realize that this cross-country trip was one of our last big joint ventures—unless you count the often lively day-to-day encounters in our living room and across our kitchen table. As we have done in museums, we have learned to live increasingly in parallel and less in unison. Sometimes I have envied couples, especially older ones, who continue to show up at concerts and movies and restaurants together, walking side by side in the fields and on the sidewalks where the dog and I take our daily turn. But I try hard not to let that feeling turn to resentment. It has been a very good life, both in unison and in parallel, as it has turned out.

So here we are in Salt Lake City. We’ve read and slept and eaten and visited three-quarters of the way across the country, but there is more to come. Do we take stock? Stop and assess what we’ve seen, where we’re going? From our journals, it seems not. It seems more that we’ve established a routine, something that helps keep our energy up, our attention from flagging. We know where we’ve been and have a sense of where we’re going next. There’s perhaps a sense of dutifulness rather than excitement at this point. Still, it is a brave new world for us, and it has such people in it that amuse and sometimes instruct us.

In the morning, we walked to the Temple Square and “inspected things Mormonesque,” notes Bill, who continues:

Not of great interest, I found, and one is subject at any moment to the approach of one of the faithful, intent upon helping one out with some not so subtle proselytizing. The male elders tend to look like Selah Tarrant (“Want to try a little inspiration?”) out of The Bostonians. The young girls who lead the tours are scrubbed and vigorous, though somewhat lacking in allure. They testify; they’re satisfied.

We walked over to the Salt Palace and Marietta inquired as to seats that night between the Jazz-Lakers. Sold out since November, the expected answer. A walk back to the hotel, carefully observing injunctions not to cross against the lights despite a complete lack of traffic in all directions. You could get arrested for that, no doubt, in S.L.C.

Some observations in the same vein from me:

After half a day, I said to Bill, I want to see a really slutty-looking woman. How ’bout a little Eastern snarl? Big wide streets, every intersection with well-designed sloping curb for disabled, traffic lights that chirp in different keys for pedestrians.

Everyone oozing officious friendliness, wants to put us on mailing lists. Young woman giving spiel to foreign tourists, lists all places they’re from. … Being watched from across the way by a sinister-looking too-friendly white-haired man in a blue suit and an older, thinner, worn version of the fresh young woman. Jill [Bill’s former student] later shows us Brigham Young’s “dormitory,” a big house where he lived with 40-some wives. In the square, flowers—tulips, daffs, huge pansies—in rigid perfect bloom. I think I detect some artificial scent, but maybe it’s just the tourists.

Bill reports that Jill, “looking good” (no Mormon, she), picked us up after our morning on our own and took us to a couple of ski resorts. After a farewell evening drink, we take the 11:30 train heading for Seattle. Bill writes:

April 12

Breakfast was taken in the neighborhood of Boise, Idaho, where nature came on in full profusion. Trees heavily budded, like Amherst in mid-May—I hadn’t expected this. … In the afternoon we left our deluxe roomette for an even better (and nonobservational) car and perched in one of the economy rooms with two seats facing each other. This proved to be a very good place to watch the splendors of the Columbia River as we moved through The Dalles and the salmon fisheries toward Portland. One felt one had seen almost enough Spectacular Nature for a while, and I became very impatient to arrive at Seattle and a few days off the train.

I am similarly impatient. Enough exciting scenery. Enough sitting for too many hours, enough being grubby, insufficiently washed. When we reach Seattle, our friends the Sales pick us up, and we pile quickly into bed.

At the Saleses’, we get not only a real bed but a real shower. Bill notes it’s “good to get sorted out and to cut one’s nails (one of the only things I’d forgotten to bring along was my trusty nail clipper).” He writes vividly and appreciatively about the food displays at Pike Place Market: “a profusion of fish and beautiful asparagus and aggressively red rhubarb regaled us.” And Bill and Roger “assessed the current state of literary criticism” and other matters.

Sunday is Easter, a holiday that, although we were both brought up in churches, Bill and I had celebrated in a largely secular way when our children were young—coloring eggs, buying chocolate bunnies, hiding them in the yard. These days Bill and I might loudly sing some Easter hymns at the piano. Otherwise, that day tended to be only minimally noted, if at all. Still, curious about what the Sales were now committed to, I was perfectly willing to go to church with them and a small breakaway group that had decided the Presbyterians were too hidebound, too predictable for them. Roger referred to his congregation as the Busted Believers. I report:

Sunday is Easter, a holiday that, although we were both brought up in churches, Bill and I had celebrated in a largely secular way when our children were young—coloring eggs, buying chocolate bunnies, hiding them in the yard. These days Bill and I might loudly sing some Easter hymns at the piano. Otherwise, that day tended to be only minimally noted, if at all. Still, curious about what the Sales were now committed to, I was perfectly willing to go to church with them and a small breakaway group that had decided the Presbyterians were too hidebound, too predictable for them. Roger referred to his congregation as the Busted Believers. I report:

Young curly-dishevelled-haired minister in a flowered dress. Congregation of 8, including me. A moving moment—a slim, elegant black man holds up a green Easter egg, tells about a three-year-old girl who has given it to him. It’s a dingy neighborhood with shootings at school, but some signs of hope.

Bill notes in his journal that he “didn’t have a second thought” about choosing basketball over prayer.

Nobody attempted to keep me from watching the Celtics, who were indeed on the tube with the Knicks at the Boston Garden, 10 a.m. Seattle time. Celts at the top of their game, at least for much of it, left the Knicks in the dust and things looked good for the future. Little did we know.

Next day, we try a different form of transportation and fly to San Francisco. There, we have an evening out with several Amherst students from the early 1960s. Bill writes: “An excellent evening, much talk about Amherst College which both men wanted to hear about.”

This is a longstanding bone of contention between Bill and me. Here’s the question: Is there a subject besides Amherst College? Bill is a lifer at this institution, having graduated from the place in 1953. He then spent a few years away, first one at Columbia in an unsuccessful attempt to become a philosopher, then four as an English literature grad student at Harvard, where he and I met. (I was an undergraduate at Radcliffe, and there was this production of The Mikado, where I sang the ingenue lead and he was the pianist.) He was then called back—a phrase inscribed on Emily Dickinson’s gravestone in Amherst, the site of many poetic pilgrimages—to Amherst at age twenty-five to begin a career that encompassed six decades in the fall of 2018. Nothing has ever held his attention and interest as much as news, gossip, complaints, and observations about this place, most especially its English department. So any evening where there was “much talk” about Amherst would count as an excellent one for him. It didn’t always work that way for me.

Although, at age twenty-one and a new wife, I had tried—and often succeeded—to fit myself into the role of Faculty Wife, decades had intervened, along with the revelations of the women’s movement and, for me, a new profession as a journalist. There was, I learned and have continued to insist, a world elsewhere.

Two days later, we rent a car, a “feeble Ford Tempo,” I write, and head north.

The Bay Bridge in the sun is all that’s promised. Next time we’ll visit the park on the other side (west) of the road, and climb the hills for an even better view. Muir Woods, just north of the bridge an amazing preserve of redwoods up and down a twisting, scary “highway” without shoulders. Here it’s damp and primordial, with tourists held onto paved paths to keep from damaging the fragile woods.

“Next time,” I wrote. That was twenty-eight years ago, and although Bill and I did some more traveling together, there was no return to that spot—and won’t be, at least not together. But my “next time” represents the traveler’s dream, the fantasy that we will remember that detail and return to San Francisco, to the west side of the bridge for a better view. Think of the much-quoted Frost poem “The Road Not Taken.” The poem’s narrator arrives at a fork in the road, and has to choose which one to take.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

We wind our way up the coast and end up at a Luxury Lodge in Bodega Bay. Bill reminds me that this is the scene of Hitchcock’s movie The Birds, but happily, no sign of any avian hordes at the moment. The Luxury Lodge, Bill notes in his journal, has a “scenic overlook.” He’s echoing a phrase from a road-trip poem by our old friend Tom Whitbread as he’s driving across country: “Scenic Overlooks Overlooked.” They’re the great views you missed as you whizzed by:

Afternoon, Blue Ridge parkway, sinuous sloth

Through sloshing fogs, our car sea-serpenting

Past Scenic Vistas, Scenic Overlooks

Overlooked, unseen, passed at no miles per hour.

Back on the train for the southern route with a stop in Flagstaff, Arizona, and a bus to the Grand Canyon. Bill is not a happy camper. “I may have been a little whiny or mournful as we pulled into Flagstaff in a brisk snowstorm,” he writes, in a rare Pritchardian version of an apology. “How could one view the Canyon in such terms?” Meanwhile, I am making some different observations.

A chilly, nervous start to our day at the Grand Canyon. The station in Flagstaff had few mod cons—only one toilet and a vending machine with candy bars—all this at 6:50 a.m. We ate grapes and nuts [I try always to have snack foods available] and waited for the Nava-Hopi bus (get it?). Went out in the mushy snow to try to find coffee and newspapers, just got wet feet. Got out my silk underwear and layered up.

The canyon lived up to its publicity. Only about 20 people on our bus, a well-versed bus driver commented on the geology, landscape, history, and told mother-in-law jokes. (I tried to buy jewelry but failed at our stops.)

The spirit of 19th century conservationism pervades the main Grand Canyon Village, a fine old rustic hotel, could be Adirondacks or White Mountains, handsome, restrained landscaping. And across the way, nature roars away. We gape at various spots, move on, gape some more. Finally a big buffet lunch just before the Italian and Japanese tours arrive. A movie—IMAX—on the way back. See nature, then see the art to tell you about what you saw. Then the world’s most expensive McDonald’s and a sleepy ride back into snow.

Bill’s gloom reminds me of the story of the travels of some friends of ours with the famous/infamous music critic Bernard H. Haggin. The friends had been touring in Italy, driving around and enjoying various sites, while Haggin had done nothing but complain and make things difficult. At a certain point, finding herself at the end of her patience, one of them turned to him and said: “Bernard, we have four more days on this trip. Let’s try to make them bearable, and then we never have to see each other again.”

The example is extreme, and there was no thought of never seeing Bill again, but I was certainly fed up with his irritability. Here is a situation where I could have—if I’d had the ability to detach myself for a minute—invoked the question: Why can’t you be more like me? There had been, perhaps, too much togetherness on this long trip. Few chances to walk away or even change the subject. My inclination was to try to make the best of it; Bill’s to retreat into complaints. So the heat of marital friction tended to flare up, but would eventually subside again. We made it through that moment, surely not the worst in our long connection.

After the Grand Canyon we head for Saint Louis, where we spend a couple of nights with a hospitable newspaper friend of mine. Then we’re back onto the train, Chicago next, and eventually Springfield. On this last leg, Bill’s spirits lift as he encounters a more familiar if less spectacular landscape. He was, after all, born and bred in upstate New York.

April 28, 1990

I woke around 5, peered out the window for a long time, eventually, an hour or so later, found we were stopped outside Buffalo. That, for some reason, pleased me. To be in New York State yet once more. We had a tremendous breakfast (especially good, I thought) seated across from an oldish black woman who turned out to be a fount of eloquence on all subjects. Riding across New York State was fine, good views of farmland, woodland, and the Mohawk River. I had never ridden across it by train, by day. At Albany we debarked briefly; they unhooked the cars to New York City, and eventually we headed home, not before noting that the Celtics had humiliated the Knicks the previous day (a hint of the future, I so wrongly thought). The route through Massachusetts is especially interesting, vivid scenery through Hinsdale, Chester, etc., up the mountain, along the dam and suddenly you’re past Westfield and chugging into West Springfield. There to be met by David, our circle completed.

We had left home and come back, seen new places and old friends, but as Proust famously said in Remembrance of Things Past, in reference to the difference it makes to look at the world through the work of different creative people: “The only true voyage of discovery, the only fountain of Eternal Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to behold the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to behold the hundred universes that each of them beholds….”

In other words, as Bill would say: Stay home and read a book.

Marietta Pritchard is a writer/editor living in Amherst, Massachusetts. She is a former features editor at the Daily Hampshire Gazette. She is the author of a family history, Among Strangers; a book about a local residential hospice, The Way to Go; and a recent memoir, Travels with Bill.