How can you tell a modern, Western country is in the midst of an existential economic crisis? Bread lines? People begging in suits? Garbage and vermin? Tumbleweed? Packs of feral youth and stray dogs?

I’m in gorgeous, light-drenched Lisbon for a two-week literary conference, staying at a residence in a drab suburb near the huge, green-and-yellow-tiled Campo Grande stadium. I ride the subways, walk up and down the hilly, chipped-stone streets, poke my nose in stores, people-watch in cafés. I try to see people’s expressions in their cars. Portugal’s economy is at its worst since 1945, its central bank says, and one of the worst-off countries in the euro zone. Yet people here go about business purposefully. They look calm, dignified, not conspicuously depressed. They dress nicely though not as expensively as Parisians or Romans.

I’ve visited France, Italy, Spain, and now Portugal in the last two years—four trips in the last eleven months, as the euro-zone crisis has deepened. All have been short visits—for vacations or for literary events, not reporting trips. Still, I like to think I have more experience or maybe interest than the average tourist to see past the beauty of these countries to the impact of the economic crisis. I used to be a financial journalist. I lived in France for four years and covered the European Monetary System crises of ’92 and ‘93.

Reading the financial pages, I hear “The William Tell Overture” or “The Ride of the Valkyries.” Stocks plummet, spike, nosedive, surge, collapse, melt down. Currencies assault resistance and smash support. Financial journalists feel compelled to turn numbers into action heroes so readers will care. I’m trying to see beyond the numbers and martial clichés of market reporting. How are people coping?

On July 11, I sit in a café near my residence drinking galão, coffee and hot milk served in a glass, and deciphering the paper. Diário de Notícias’ lead story is: “Portugal Has Destroyed 600,000 Jobs Since 2008.” Portugal’s unemployment rate is 15.6%. Spain’s is 24.6%, the highest in the seventeen euro-zone countries, where 17.6 million people have no jobs. A quarter of people under 25 are out of work. In Spain and Greece, the youth jobless figure is around 50%. U.S. unemployment is 8.2%, and we think we have it bad.

Perhaps other Western economies have such a cushion of wealth and development that we can’t see the extent of poverty yet. But Portugal never had much of a boom. For the last ten years, its economic growth averaged less than 1% a year. I don’t see much development in my wanderings. Shouldn’t a catastrophe of this magnitude be obvious, even to a foreign tourist? There is almost no way to write this without sounding insensitive. I ask others at this conference what they’ve observed and get similar responses. “It’s odd… not much really… must be able to see in other neighborhoods, out of town, in the small villages…” A Portuguese-American writer with deep ties here talks about his excursion to a remote village. Must look pretty bad out there? He shakes his head. Not really.

One sign of hard times: Endemic graffiti, some political—“People could live here” scrawled on abandoned buildings; “Revolt”; a portrait of Lenin. Taggers are even defacing Lisbon’s historic glazed-tile façades, with their gorgeous blue-and-white murals of saints and explorers. Authorities have adopted the tactics that rid New York of this scourge in the eighties, cleaning daily and letting taggers write on designated buildings and win artistic recognition. At this point, I’d say the taggers are still winning this guerilla war.

My husband, two children, and I spent Christmas in Sicily. Mario Monti had just taken over as Prime Minister from Silvio Berlusconi. Italy was on its fourth austerity plan. In Palermo, rain-soaked garbage bags overflowed from dumpsters into streets, where dogs tore them apart. Maybe the garbage men had off for the holiday. Trees grew out of picturesque shells; artisanal scaffolding propped up collapsing façades. How different was it from my last visit, in 2006, when the euro-zone unemployment rate was 4%? I remember joking that the potholes made me feel at home. Just like the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway!

In Sicily, blame the Mafia first. Everyday, we drove over the bridge where Giovanni Falcone, the heroic Mafia prosecutor, was assassinated by car bomb. Obelisks commemorate him on both sides of the highway. Floes of E.U. subsidies were diverted to criminals. What happens now that they’re drying up?

I was in Paris between rounds of the presidential election. Sarkozy, the tone-deafprésident bling-bling, lost to a Socialist. My friends are working, though Didier, who’s in the hotel business, says things are awful, shaking his hand in that French way, as if he’d burned his fingers. In St.-Germain, meanwhile, boutique salespeople seem more eager than usual to help a browsing customer. There were clochards, but Paris will always have clochards and gypsies in the Métro. “Excousez-moi, m’siou dames, je suis de la Roumanie…” Sarkozy’s policy of deporting Roms was seen as pandering to the far right. But even among my mostly centrist-to-left friends, I heard little sympathy for them.

German unification triggered the EMS crises of the ‘90s. West Germany generously swapped worthless Ostmarks for Deutsche marks at a one-to-one parity. The inflation-obsessed Bundesbank jacked up interest rates, and the other European central banks had to follow to support their linked currencies. Jobs vanished across the continent. The sanctimonious Germans never mention this old favor. Today’s unemployment numbers are far worse.

In New York, when the delayed aftershocks of the 1987 stock market crash hit the economy, crackheads went where the money was—their gentrified ex-stomping grounds. Everyone—myself and my husband included—got mugged. Neighborhoods ungentrified. When we were transferred to France in December, 1990, I couldn’t give away my Brooklyn apartment.

These days, property values in my neighborhood keep rising. I consider this a contrarian indicator, despite recovering U.S. economic growth. This school district has good public schools, so buyers are willing to pay more to live here if they won’t have to spend $360,000 per kid for eight years of private school. Ten years ago, they wouldn’t have considered public school, no matter how good.

Another unconventional indicator: What seemed to be Eastern European gypsies in the New York subways, something I’ve never seen. France kicks them out, they show up in New York? How do they get in? An accordion player and two school-age children worked the F train this winter. More recently, two young women carrying babies and identical signs, making that food-to-mouth gesture. I didn’t give them money. I know that begging with children is a marginalized, persecuted people’s survival strategy. But my own children were adopted from Guatemala, Latin America’s second poorest country. I couldn’t help but see how others might have exploited them. A few years ago, in Istanbul, we saw a blond, apple-cheeked girl the size of a three-year-old, sitting in the rain, day after day. We asked our hotel manager about her. Nothing can be done, madam. Someone was watching—to make sure she stayed on the job, presumably.

There are sales in every store window on the Chiado, Lisbon’s tourist shopping street. Summer sales, crisis, or both? I bought a designer jacket at a great price. Portugal seems to be the last bastion of good value for money in Western Europe. Two shopkeepers apologized for a lack of inventory. They keep as little as possible now.

Two people in our group were robbed in one night.

On the Rua Augusta, a six-block pedestrian street connecting two grand praças, I saw six fake-statue acts and a woman accordion player.

On my next-to-last day, Lisbon teachers demonstrated politely and briefly on the Chiado.

There’s a tradition of foreigners gawking at Portugal’s misfortunes. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, brought rationalist philosophers from France and gentleman travelers from England to witness the imperial city shaken, burned, and then flooded by the tsunami that followed. They debated its causes. Was this God’s punishment? After the earthquake, Voltaire wrote Candide to skewer optimists who claimed we live in the best of all possible worlds.

Maybe the euro-zone crisis is a waterless tsunami. Think the worst has passed and boom—

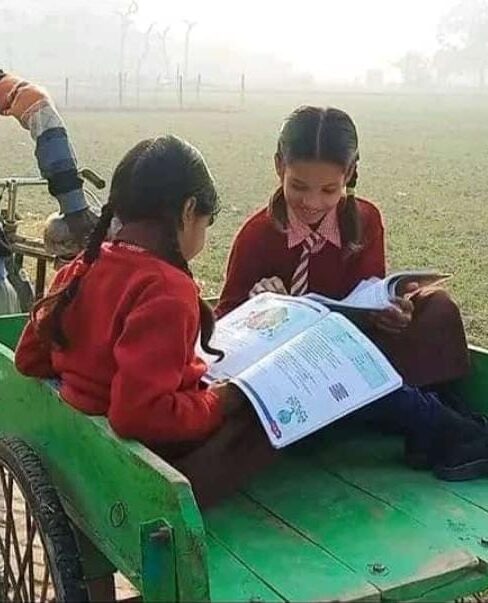

One morning, I got on the subway at Campo Grande with an older man and a boy of eight or nine. The man carried a zither; the boy a violin. The boy, who wore a fedora, had dark hair and eyes, light-brown skin and a sweet, tense smile. My twelve-year-old son plays violin. I gave him a euro. The boy worked through a professional repertoire of standards. “My Way”, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, “Bésame Mucho.” He played impressively, striking his bow on the strings with the attack of a mature player. They played four or five songs, unlike New York train buskers, who give you one at most.

Eight hours later, when I returned to my residence, they were still at it. Both looked exhausted. I turned to the woman next to me and said (in Spanish, since I only know a few words of Portuguese), “I saw them this morning. That child has been playing all day.”

The man across from us, who wore a business suit, put down his paper and explained to an obvious foreigner, “Romênia… Ou talvez, Ucrânia.”

The woman was in her fifties, I guessed. She had peroxided hair, a lined face, and wore a simple dress. “E complicado, é complicado,” she said. Her kind tone and expression surprised me. She didn’t seem like someone who’d be particularly sympathetic to gypsies. She said in Portuguese, repeating herself to make sure I understood: “I have two sons, both 22, twins.” She smiled at the thought of them, then her face turned sad. “They can’t find work. Nothing. E complicado, muito complicado.” When the gypsy passed his hat, both the man and woman gave.

Julia Lichtblau’s writing is forthcoming in The Florida Review and has been published in Best Paris Stories, Temenos, Ploughshares blog, Narrative, Pindeldyboz, and Tertulia. She won the 2011 Paris Short Story Contest, 2nd Prize in The Florida Review’s Jeanne Leiby Chapbook Contest, and has been a finalist for other literary awards, most recently the Gold Line Press Chapbook Contest. She has an MFA from Bennington College. For 15 years, she was a journalist for Dow Jones and BusinessWeek in New York and Paris. She’s working on a short story collection, Foreign Service, and a novel, Sweet Melissa.