By MICHELLE DE KRETSER

Reviewed by AMBER RUTH PAULEN

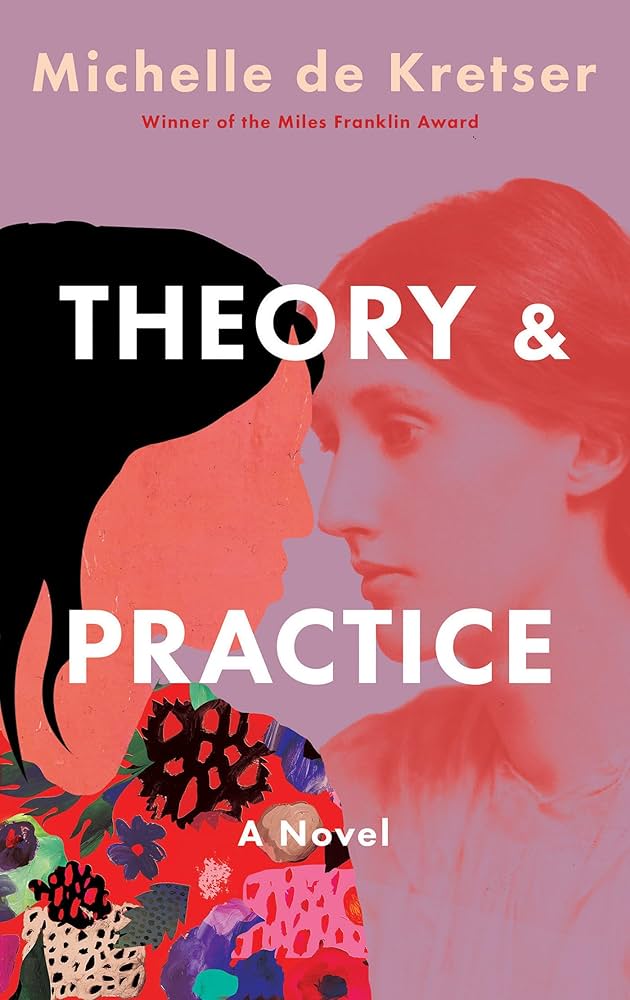

One of the brilliances of Michelle de Kretser’s newest novel Theory and Practice is how the author lassoes life’s “messy truths” into a neat and slim book. To do so, de Kretser asks many questions at once: How does shame lead to silence? Why write? What to feel when an idol falls from grace? How do you break free from your mother (the Woolfmother included)? How do class and race determine your place in the world? What to do when life doesn’t fit your ideas about it? Additionally, de Kretser remains flexible in form: fiction blends with essayistic, academic, and autobiographical elements. Even the cover of the Australian edition features a young de Kretser, as if to say, this book might be about things that have actually happened. With so much going on, it might seem like the book would fall apart, but it is a concise and searing portrait of what it’s like to be alive in a certain place and time and body.

The central plot begins when the mostly unnamed narrator, in her mid-20s, moves from Sydney to Melbourne’s St. Kilda to study Virginia Woolf. Shortly into her graduate research, she reads the following in Woolf’s diary: “the poor little mahogany coloured wretch has no variety of subjects.” Woolf was writing about E.W. Perera, a Ceylonese man who came to England in 1917 to try and save his countrymen from the colonizers. Woolf found his concerns tiresome, and he made her “uncomfortable.” The narrator of Theory and Practice is also from Sri Lanka. The diary entry takes the air from her lungs.

She approaches her advisor, Paula, to change her topic from gender to race, but it’s the mid-1980s and Paula advises her to stick to analyzing the fictional texts. Paula wears a black leather jacket, is the university’s “Designated Feminist,” and tells the narrator “not to focus on what came down to a very small fraction of the millions of words that Woolf produced.” She says that racism was “everywhere at the time” and in this attempt to excuse Woolf, Paula encourages the narrator to brush the racism aside, to instead rely on Theory—French poststructuralism—to bring new meaning to Woolf’s later novels. Paula’s insistence on silence isn’t new to the narrator but this time, she has trouble following the advice.

Yet she doesn’t start writing immediately. There are other things going on in her life. Perhaps as a result of the diary entry, she stops seeing Kit, the man she is sleeping with. Her decision happens as if it were made by someone else: “I heard myself saying that I didn’t want to see him again. Kit’s face grew formal, but he didn’t ask why.” At least, as a reader, I wasn’t the only one surprised by the narrator’s sudden turn of mind. In a novel that uses interiority as skillfully as Theory and Practice, the reasons for the narrator’s break up with Kit remain as unexamined as his Anglo middle-class privileges, especially in light of the diary entry. Instead of thinking about Kit, she becomes fixated on Olivia, Kit’s girlfriend with whom he’s in a “deconstructed” relationship. The trouble isn’t the obsessive jealousy itself, but that it goes against the feminism she has aligned herself with and that is practiced by all her friends at the time.

She begins to hang around the street where Olivia lives. She buys a shirt she saw Olivia wear. When she bumps into Kit while hoping to see Olivia, he spends the night. In this brief, second phase of their relationship, the narrator becomes determined “to obliterate Olivia, to blast her from his mind.” She leaves bruises on his skin, and Olivia leaves bruises in exchange. The narrator reflects, “Olivia and I were exchanging messages about possession and power.” But Olivia and the narrator never confront each other, and Kit is the one to leave the narrator. This time, she thinks about Kit too. And unlike the discovery of Woolf’s racism, the narrator doesn’t speak to her circle of friends about her jealousy—which moves beyond Olivia’s relationship with Kit to Olivia’s solid and easy status in the middle class. It’s such a shameful secret that the only option is to keep quiet.

These two events propel Theory and Practice forward, but they get their heft from the reason the narrator has chosen this year of her life to focus on. As we learn in the beginning, the narrator is a writer. Theory and Practice starts as another novel about a young man traveling in Europe in the 1950s. After some pages of mountain climbing and backstory, the narrator in the present elbows in: she’s going to abandon the fiction because “particles of [the breakdowns between theory and practice] had entered [her] novel and jammed up its works.” Instead of a fictional story about an imagined character, the narrator decides to write about her own past “to stop fearing shame” and tell the truth about her life.

From here, the narrator moves on to a summary of a 2021 essay in the London Review of Books by Eyal Weizman. In “Tunnel Vision,” Weizman explains how an Israeli military commander adopted poststructuralist theory in his raids of West Bank cities. Instead of using streets to move through the Palestinian cities, the commander sent his soldiers through buildings, breaking down walls and homes in a “reinterpretation of space.” De Kretser positions Weizman’s essay as a destructive and harmful example of theory taken literally. Even when it is not used as a war tactic, the big problem with Theory, the narrator observes during her struggle with Woolf, is that its application to a text is like an act of torture, of destruction. After probing and interrogating, “[the Story Under The Story] was revealed, the text was in pieces, [and] the critic had won.” The job of academics and critics is to arrive at some clear yet hidden meaning by pulling apart and relentlessly investigating what an artist creates.

Though this push and pull of creating and destroying was only one of the threads of this novel, it was the one that I kept returning to, identifying with and at the same time bristling at the idea that analysis can’t be creative. De Kretser positions academics and critics on the destruction side of the spectrum and fiction and creative non-fiction on the other, positive side. But in practice, throughout Theory and Practice the division between the two genres is not always that clear. Take the narrator’s efforts to reconcile Woolf’s racism. In defiance of Paula, she writes a post-grad seminar lecture about class, colonialism, and race in Woolf’s The Years. Compared to the thesis she eventually writes, entitled “Adventuring, Changing: The Gendered Self in the Late Fiction of Virginia Woolf,” the seminar lecture is on the topic of her choosing and positions Woolf as a complicit member of the bourgeoise colonial class. While the narrator later remembers the thesis with a “shiver of shame,” the narrator at the same time felt a sense of accomplishment and pride with her lecture. If the point of university was to help the narrator fit into “the classy world at which [she] was aiming,” then at least this lecture allowed her to confront the system’s class and racial biases directly.

And then there is the hybrid form of Theory and Practice—both as a novel written by de Kretser and as a memoir written by the narrator. After her thesis the narrator at some point drops academia for fiction and then, to write this book, drops fiction for memoir. The novel fragment at the beginning of Theory and Practice is easy to forget about once the narrator starts her story about living in St. Kilda. For a book of only 175 pages, the 10 of the novel fragment are actually quite a lot. The fragment is one of the many ways that de Kretser (and her narrator) “writes back to Woolf.” As the narrator analyses in her lecture, in The Years Woolf “had set out to find a fresh form … but had later abandoned the attempt. A fresh form represents a desire to see the world differently, but Woolf hadn’t managed to do so.” The abandoned novel fragment gives Theory and Practice a “fresh form” that is followed through, making this novel not one genre or another. Instead of the strict binaries of creation-destruction, fact-fiction, theory-practice, Theory and Practice occupies the blurry middle where living happens. It is exactly this flexible quality of de Krester’s writing that keeps me coming back to her novels: to read a book like Theory and Practice, a book wide open to interpretations and not afraid to push boundaries, is in itself the biggest affirmation of the creative-destructive powers of art.

Theory and Practice is bookended by a return to the narrator’s present. She runs into Olivia’s cousin after a reading from one of the narrator’s historical novels. She learns that Olivia is dead and that she and Kit didn’t last as a couple after their time in St. Kilda. After this conversation, the narrator looks up Kit online: he has become rich working for an extraction company in other countries. In a photo, he stands besides his wife in a living room decorated with “eclectic treasures” from his travels. She wonders if “his dealings with women still unfolded as Capture and Take and Shoot.” Older and shorn of her desire and jealousy, she can critique his white male privilege. The shame of Kit was not only her jealousy of Olivia, but also how she desired a man like him.

In order to examine shame one step further, the narrator cuts next to an essayistic section about the Australian pedophile Donald Friend and how his friends in later interviews “defend Friend, denying or making light of his crimes.” Like in the 2019 Newsnight interview with Prince Andrew, Friend’s friends practice a “blanking of victims,” the Balinese and Sri Lankan children Friend sexually abused. The narrator is not saying that Kit is a sex-offender like Friend, but I do think that by this juxtaposition she’s helping us see how he, like these men, “appear not to recognise any reality larger than their own.” They are men who “refuse to be shamed.” As a woman, an immigrant and a person of color, as someone who was sexually abused as a child, the narrator has made truth out of shame, art out of truth.

Early in the novel the narrator reflects: “An artist once told me that she no longer wanted to make art that looked like art. I was discovering that I no longer wanted to write novels that read like novels. Instead of shapeliness and disguise, I wanted a form that allowed for formlessness and mess.” This statement could just as well be the guiding one for Theory and Practice. By digging into the “messy human truths” and in the process transforming them into art, de Kretser has written a masterful novel that defies easy categorization and shows us a way beyond silence and shame.

Amber Ruth Paulen is a writer and educator living in rural Michigan. She earned her MFA in fiction at Columbia University and is currently writing a multi-generational novel about the struggles to keep one family farm running and the costs of an inheritance.