Hello, everybody. My name is Julia, and I am becoming an Internet genealogy addict. I don’t believe in higher powers, except, like, the NSA and the IRS. So I must rely on my failing willpower. Unless you find a rich uncle, Internet genealogy is hard to justify as useful. Why should I care that four hundred years ago, some remote ancestor was a rabbi in Moravia? Geni.com, where I listed my family tree, says it has 74,346,170 people on its site. I’m already up to 1,820 blood relatives.

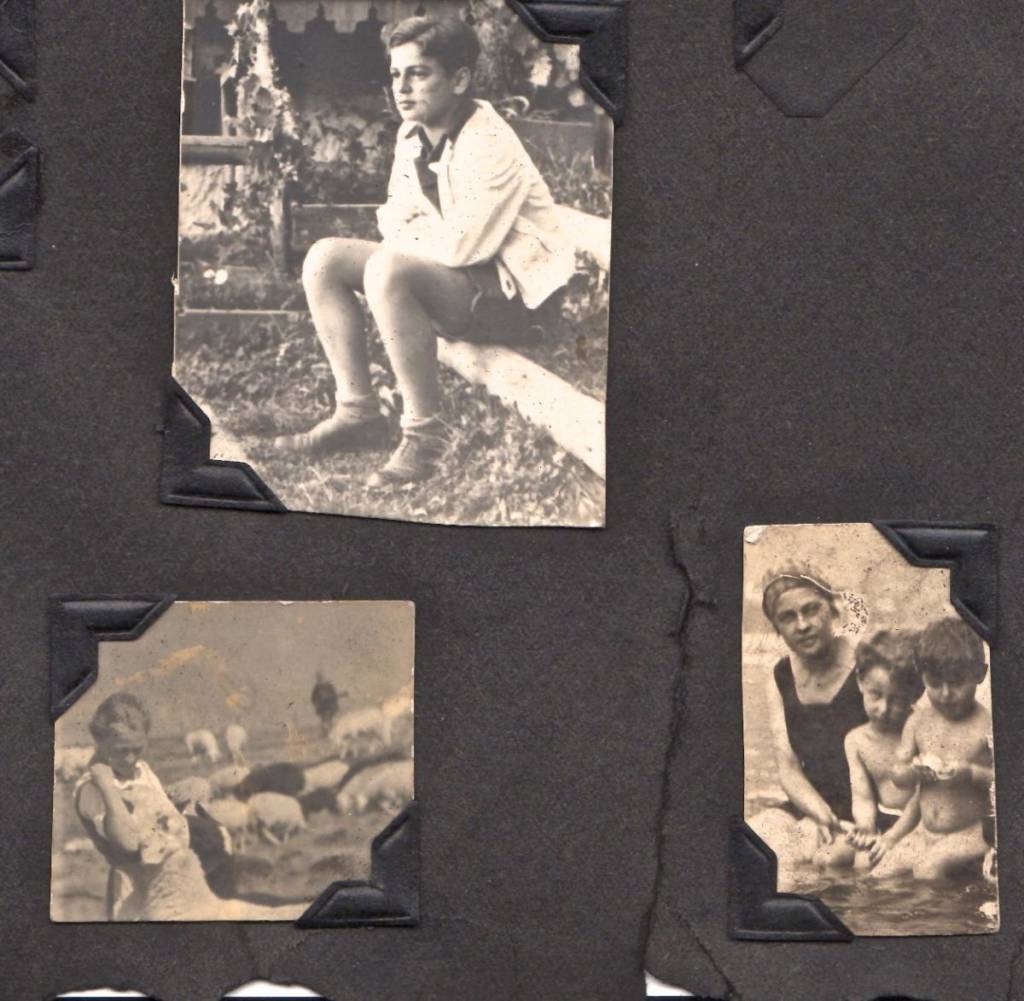

(clockwise) My uncle, Hans Lichtblau, in Austria; my grandmother, Alice Fischer Lichtblau in the Tyrols; Alice, George (my father) and Hans Lichtblau

(clockwise) My uncle, Hans Lichtblau, in Austria; my grandmother, Alice Fischer Lichtblau in the Tyrols; Alice, George (my father) and Hans Lichtblau

My cousin Ron turned me on to this, but I don’t hold it against him. We’re good friends. He put his tree on Geni, which sent me an alert. How could I resist looking myself up? Besides, I wanted to know exactly how we’re related. His father was from Prague and mine from Vienna (which admittedly isn’t like crossing the Bering Straits land bridge.) My father and uncle remembered his father, who became an Israeli officer, as a “naughty little boy,” not useful, genealogically speaking. Now I know. Ron is my third cousin; my great-grandfather, aka his great-uncle, made the Great Schlep to Vienna, probably by train.

This is how they suck you in. You fill in the pink (female) and blue (male) rectangles above a name. Immediately, another set of rectangles invites you to “Add This Person,” which you do, and two more pop up, and so on. It’s weirdly satisfying and so much easier than taping pieces of paper together and drawing boxes that constantly run off the edges, so you keep filling in the pop-up boxes begging to be filled and hunting around the Internet for people to put in them, until next thing, the kids are yelling, “Yo, when’s dinner, ma?” and you realize you never took a shower today. If you make your tree public, other addicts hunt you down and suck you into their research. Tantalizing emails arrive: “Julia—You have 18 new tree matches on Geni.” But the site blocks you from seeing them unless you spend $112 a year for a PRO membership.

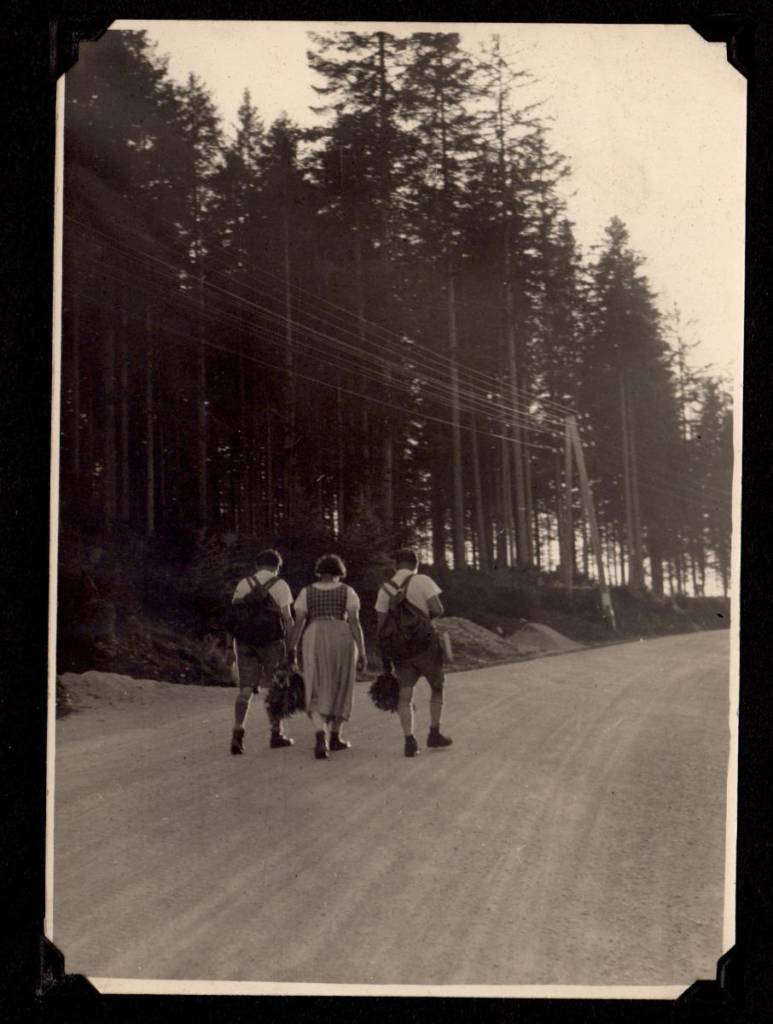

The Last Hike, 1938. George, Alice, and Hans, before the boys were sent abroad. They didn’t know if they would ever see each other.

The Last Hike, 1938. George, Alice, and Hans, before the boys were sent abroad. They didn’t know if they would ever see each other.

I ran out of known relatives at 1811, which sent me fishing around the site. I found more in other trees. I emailed the managers of those trees. They emailed back, asking to link their trees to mine. My tree became a twig in the aboriginal Mitteleuropean forest. The managers were pushy. One told me that I got my great-aunt’s name wrong, and proved it with a copy of my great-grandfather’s death notice in a Viennese newspaper that listed all his immediate family. Who was this guy and why did he have my great-grandfather’s death notice? Turns out a group of genealogy hobbyists are piecing together the family trees of the Jews of Central Europe. One researcher is my first cousin thrice removed’s wife’s aunt’s husband’s brother’s wife’s first cousin thrice removed. After a few days, I saw that this was the road to never finishing my book or anything else that might justify my existence.

But I was still curious about the French branch of my family, established by my grandfather’s uncle, Léopold, whose daughter supposedly married a Corsican nobleman. His son lost a leg at Verdun. His grandson, Michel, was in an institution. The last I’d heard about them was when I lived in Paris in the 1990s, and a French genealogist called to ask if I was related to Michel. Something about an unclaimed inheritance of apartments on the Quai Henri IV. Nothing came of it—for me, alas. But, I do still wonder about those apartments. I signed up for a French genealogical site and found, on a tree of over 19,000, its branches heavy with noms à particules—an aristocratic “de”—Léopold and his wife, Céline. Wow. Céline’s last name was Weill, which is also the name of some very wealthy French financiers, though I could find nothing about her. He must have done well for himself, l’oncle Léopold. I couldn’t help but be impressed.

I sent the tree manager an email, then another. From his impeccably courteous responses, I deduced that the last thing he wanted was an open-ended conversation about Jewish relatives. He did, however, add Léopold’s children to his tree. The daughter’s name was Jane-Reine, not Jeanne (pronounced “Zhahne”) as I’d assumed. Jane-Queen? Was that a made-up “fancy” name—like Velveeta? In Swann’s Way, everyone from the maid, Françoise, to the Princesse de Guermantes drips contempt for people like that, especially Jewish ones. Did l’oncle Léopold have a laughable Viennese accent? Jane-Reine did marry a count and her brother earned the Légion d’Honneur. So there. I wonder how much good either did them in 1940 when Pétain surrendered to the Nazis.

My grandfather, Ernst Lichtblau, and Alice—“eine beauté.” 1930s

My grandfather, Ernst Lichtblau, and Alice—“eine beauté.” 1930s

This brings us to the silliest reason to get sucked into genealogy: Famous relatives. Why silly? Well, for example: My great-grandmother was a Herzl, supposedly connected to Theodore Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, the Jewish George Washington. The Herzl clan has an industrial-sized family tree. I couldn’t find Great-Grandma, but I’m connected on my father’s mother’s side and on his father’s side. Thanks to my Scottish-Irish mother, I don’t have six fingers. (Ashkenazi Jews, those of Central and Eastern European descent, suffer from a nasty constellation of genetically transmitted diseases.)

From there, I discovered a Web page that connects the Herzl clan to the Hapsburgs, Winston Churchill, President Obama, Margaret Thatcher, Franz Werfel, Sigmund Freud, Saul Wahl Katzenellenbogen: “King of Poland for 1 Day,” John Kerry, John Kennedy, Vincent Van Gogh, Madeleine Albright, and yes, Moses.

Randomly clicking through a list of 253 Jewish surnames from the 1794 census of Prague, I was related to every one, including Kafka (“Franz Amschel Kafka is your first cousin thrice removed’s wife’s uncle’s wife’s niece’s husband’s first cousin.”) Yes! Did Kafka waste time on genealogy? No sir, he imagined waking up as a giant cockroach, and look where it got him.

Last week, I suddenly needed to know if the name Lichtblau really did come from a Silesian deposit of blue clay. Yes, Silesia is indeed known for blue clay. But that’s as far as I got. I’m embarrassed to say that I frittered away an entire evening on this question.

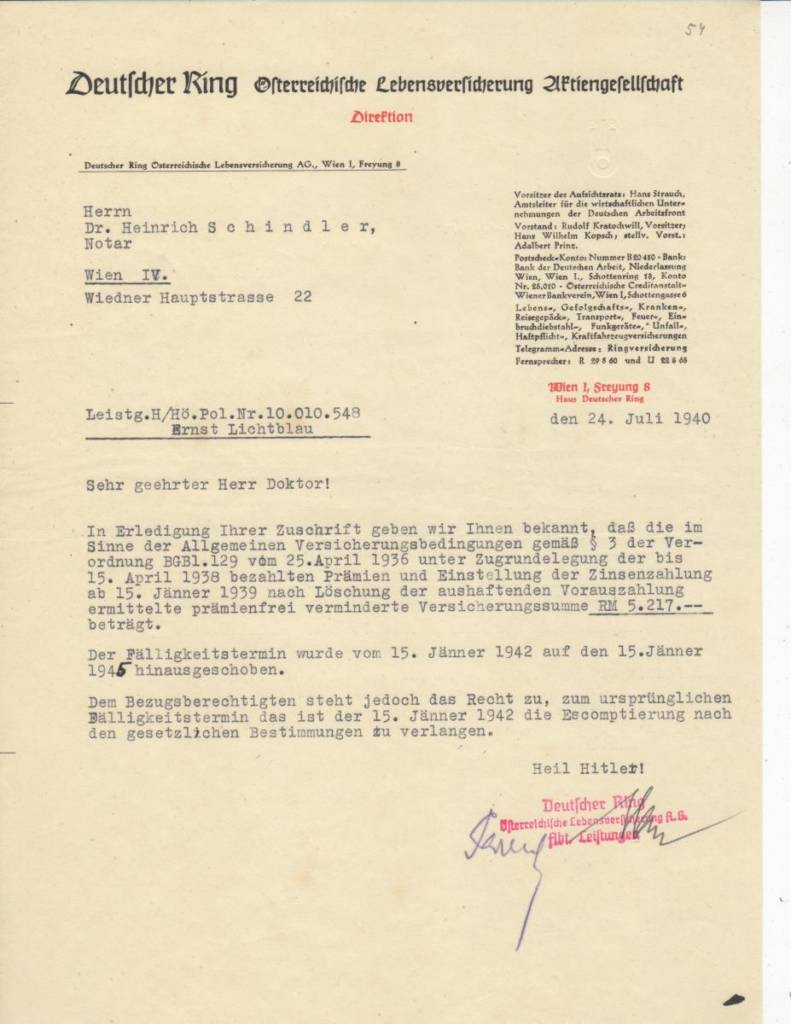

Letter from an insurance company official to my grandfather about his insurance policy, found by the Holocaust Commission in 2011. Note the signature: “Heil Hitler!”

Letter from an insurance company official to my grandfather about his insurance policy, found by the Holocaust Commission in 2011. Note the signature: “Heil Hitler!”

The roots of my tree stretch into Moravia, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, towns with names in different languages, depending on who controlled them—Pressburg/Bratislava, Senica/Szenitz, Loštice/Loschitz. I found the transport numbers that took my grandfather’s sister, Rosa Knöpfelmacher, and her husband, Heinrich, to Theresienstadt and Treblinka in a vast genealogy that traces the descendants of Rabbi Judel Knöpfelmacher—the name means button-maker—to 1645. In the midst of a very long line of begats is what amounts to a memorial to an entire generation who died in concentration camps. I was too young to ask my grandfather about his sisters and brothers before he died. For some reason, Rosa fell out of family lore, unlike her sister, Julie, whom my uncle (her nephew) located in a displaced persons camp, a story no one ever tired of. He appeared in his American officer’s uniform and asked if she recognized him. “Ja, du bist Hansi,” she said. The two sisters had similar married names—Knöpfer and Knöpfelmacher. In the endless retelling, the sister who survived mysteriously acquired the last name of the one who was killed. Was this some sort of Freudian slip, a subconscious, tribal way of honoring Rosa? Julie is my namesake, so it was all the more peculiar to find we’d gotten her name wrong. I have a photo from 1953, the year she died, a gaunt, long-faced lady in a black coat and pillbox hat. But all I knew of her until now was the story of her being found.

I’m glad I found my great aunts and uncle. It was comforting to find shared memory, without which shared DNA is mostly a curiosity. I’ve always known many things people want to know about their ancestors—on my father’s side, anyway. What country and social class they came from, what languages they spoke, their ethnic group, religion, the stuff of social and cultural identity. After leaving Jewish enclaves, they prospered, assimilated, and lived a bourgeois life until 1938, when they fled or were killed. What I’ll never know from fishing around on the Internet and reading scanned birth, death, and marriage notices is what made them give up their religious observances—there were rabbis in the mix back then. Money? Persecution? War? Convenience? A suspicion that there is no one Up There? When my uncle was thirteen, my grandfather asked him if he wanted a bar mitzvah or a bicycle. “I chose a bicycle, of course,” my uncle says.

What makes Internet genealogy so alluring is that it’s easy—if time-consuming. You can find handwritten, sepia-toned records from Vienna and Prague and Paris in your bunny slippers. No need to fly across the world and ask some clerk (who doesn’t speak English and has his eye on his lunch break) where to find the register for people born before 1938.

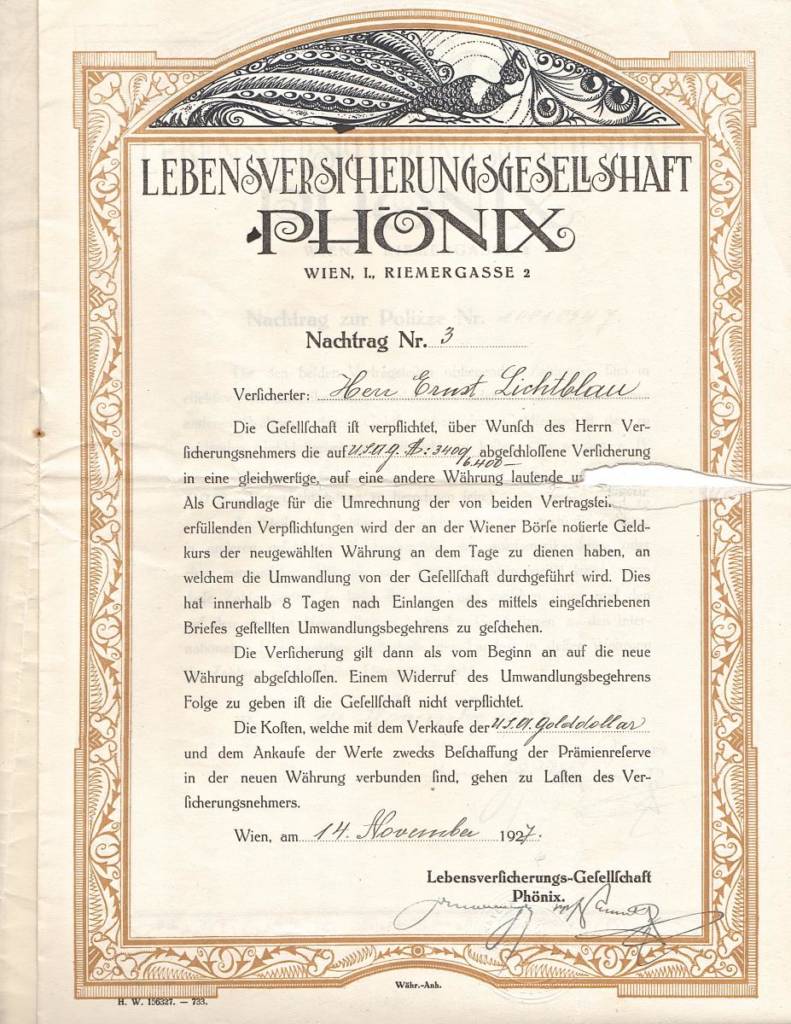

My grandfather’s 1927 policy. Note Wiener Werkstette artwork.

My grandfather’s 1927 policy. Note Wiener Werkstette artwork.

I would have to go much deeper to find the narrative. Kick off the bunny slippers and catch a plane. What would I find? Their possessions were taken, their houses despoiled, letters and diaries destroyed. The website of the ancestral burg of Lostiče, Moravia (Czech Republic, population 3,000) advertises itself today as “the metropolis of a unique smelly-cheese.” Maybe the best I can do is make fiction out of what I have.

There is no end to ancestor worship, which is the proper name for this obsession. People, we need to live in the present. This is why I’ve largely steered clear of tracing my mother’s family—Burkes, Andersons, Flynns—who are enigmas to me, though they’re from Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Long Island. The names are common, but their birth, marriage, and death certificates are temptingly accessible in the New York City municipal archives. Maybe I’ll write a story about hard-boiled Irish newspaper people. Then I’ll have the perfect excuse.

Julia Lichtblau is the Book Review Editor for The Common. Her writing is forthcoming in the American Fiction 13 anthology and has appeared in Narrative, The Florida Review, Best Paris Stories, Ploughshares blog, and elsewhere.

Photos by author